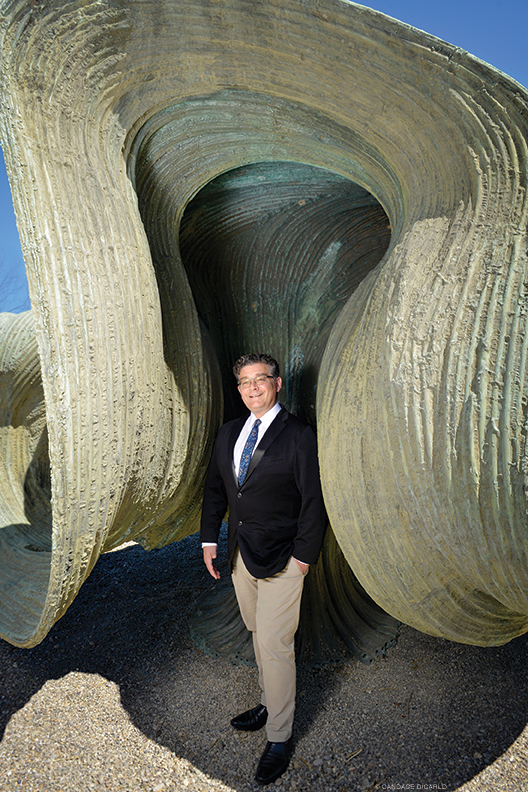

Valerio with Harry Bertoia’s Free Interpretation of Plant Forms, which he convinced the city to move to Woodmere.

Valerio with Harry Bertoia’s Free Interpretation of Plant Forms, which he convinced the city to move to Woodmere.

“We’re the museum of Philadelphia’s artists,” says William Valerio G’87 WG’04, the director and CEO of the Woodmere Art Museum in Philadelphia’s Chestnut Hill section. “So how is the art of Philadelphia different from that of other places? Part of it has to do with different structural aspects. In New York, for example, commercial art galleries are the center of the art world. In Philadelphia, schools are, and each has a different mission and a different roster of important artist-teachers who attract students to them.”

The 53-year-old Valerio may have been born in Bologna, Italy, but he grew up in New York, “where it’s competitive, people strive, people want to show their success,” he says. “And then I came to Penn and found that ingrained in Philadelphia and the University, with their Ben Franklin background, is a great sense of civic involvement. I think a lot about that here at Woodmere.”

He points to a current exhibit, The Journeys of John Laub (through August 13), a look at the work of a Philadelphia artist whose intensely hued landscapes are both vivid expressions of joy and sheer exultations in the delights of color.

“Neil Welliver was one of the great artists [and chair of the fine arts department] at the University, and I’m told that Laub was one of his greatest students,” Valerio says. “That’s a perfect example of these circles of artists that grow up around these wonderful teachers, and that’s how I see a lot of the history of art in Philadelphia progressing. That’s very much the story we tell here at Woodmere, and we’re constantly constructing that story.”

Housed in a Chestnut Hill mansion, the museum was founded by an oil magnate-cum-city official, Charles Knox Smith. He purchased the Victorian home in 1898, added on two galleries to house his private collection, and in 1910 began inviting the masses to mingle with the art on select evenings. Smith died a few years later, but it wasn’t until 1940 that Woodmere officially threw open its doors as a public institution.

Today the complex features a mix of traditional gallery spaces and elegant rooms adorned with marble fireplaces and stained glass windows. Its collection ranges from the original group of Hudson River School paintings owned by Smith to works by such prominent Philadelphia artists as Charles Willson Peale, Benjamin West, Alexander Calder, Violet Oakley, and Sidney Goodman.

When Valerio arrived in 2010, he found a sleepy institution that “wasn’t any fun,” he says. Now it offers a packed calendar of almost daily extracurricular activities, including Tuesday Nights at the Movies, Friday Night Jazz, Classical Saturdays, family events, lectures, and classes.

“People need to enjoy their time here—this once was somebody’s house, and we want people to feel welcome,” Valerio says. The approach seems to have worked—during his tenure, annual attendance has nearly tripled, from 15,000 to 43,000.

Valerio says his two Penn degrees—a master’s in fine arts and an MBA from Wharton—represent “everything I do at the museum,” referring to the sometimes-tricky balance between art and commerce that comes with the territory. As a kid growing up in Brooklyn, though, he was firmly schooled in favoring the first. His “hippie” parents—mom was a painter, dad a fiction writer—were “museum junkies, the type of people who got kicked out by the guards at the end of the day.”

At Williams College, he majored in art history, then came to Penn to further what he calls an “ingrained talent for understanding the language that the arts speak.” He planned to be a scholar of the Italian Baroque but soon realized that he “needed to live, professionally and intellectually, in our own times.” After earning his PhD at Yale—still focused on Italy, though his dissertation examined Futurism and Fascist Modernism—he moved back to New York as a curator for the Queens Museum. But he gradually realized that it would be nice to pursue “some kind of a career in museums where I could have a living wage”—at which point a Wharton degree beckoned.

On returning to Philly in 2002, Valerio found that a certain special something was missing: Harry Bertoia’s undulating bronze and copper sculpture, Free Interpretation of Plant Forms (1967), which had once stood in front of the Civic Center.

“I remember it as being this magnificent focal point—students had their graduation photos taken in front of it,” he says. The installation wasn’t ideal—“It was a pretty hard-edged setting for this beautiful organic piece”—but it was a “touchstone” of his Philadelphia experience. He eventually discovered that the city had placed it in storage, in preparation for the Civic Center’s demolition.

As he began a professional career in Philadelphia—including six years at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where he ended up as its assistant director for administration—his thoughts periodically turned to the Bertoia work. Assuming the helm at Woodmere, he saw a chance to give the piece a home at last.

“I had a conversation with the curatorial team of the city,” he says. “I described my great love for the sculpture and made the case for why I thought Woodmere might be an appropriate setting for it—including that Bertoia had lived and worked just 45 minutes from the museum.”

The persuasion worked, and later this year the freshly conserved piece will be unveiled as part of a larger renovation of the museum’s grounds and sculpture gardens. The upgrade was implemented with the input of experts from the neighboring Morris Arboretum.

“We’re breaking out into the landscape,” Valerio says. “It’s a big part of what I wanted to do. Woodmere is an experience that offers art and nature together, and that intersection is where I think that Woodmere can have a national profile.”

—JoAnn Greco