He asked, “Hey, so, what’re your halves?” It was love.

By Alison Stoltzfus

What people don’t understand when I try to explain to them what it means to be an Asian-Caucasian biracial in America is the tension. This is America, a land where the races are always at war with each other, whether subtly or overtly. This is America, where someone will always look at you and decide they know you by your skin color, the shape of your eyes, the arch of your nose. Why, they ask, should your tensions be any different?

Let me try to show you what I mean:

I sat uncomfortably in my Mandarin Chinese class, hoping desperately that the professor, my laoshi, wouldn’t notice me, but there were only five students in the class. When he got to me—“Wu Jia-Ling,” he said, “Xiage zhoumo ni zou shenme?” —I blinked stupidly and heavily and felt the whip of panic uncoil deep in my stomach. It made my tongue leaden and my lips stiff. After a few beats of awkward silence and a stumbling attempt on my part to ask him to repeat his question, one of my classmates leaned over.

“He asked, ‘What’d you do this weekend?’” she prompted.

“Ha-ha-yes,” Yang Laoshi said in a little rush of forced laughter. “This same thing, I ask it every week. Not so hard, hao?”

“Hao,” I replied, sliding lower in my seat, silently hating the laoshi, my easily conversing classmates, my clumsy tongue, and my slow brain and myself. I could feel the low red flush of humiliation burning on my cheeks.

It took me a month to drop that class, useless as it was and prideful as I am. No one could understand why I persisted in doing the homework I hated, copying characters till four in the morning, then dragging myself out the door at 9 a.m. to be humiliated yet again.

They couldn’t understand because they were all either Asian or Caucasian. They had one tongue or maybe two, but they belonged to those languages. They didn’t know that I had always promised myself that in college I would at last learn Chinese, to me the symbol of claiming the culture that should have been mine. They didn’t know how disappointing—and, in many ways, surprising—it was for me to realize that, not only was there not going to be a miraculous and mysterious awakening of some Chinese sixth sense at the sound of the tones and syllables but that, in fact, learning the vocabulary was going to be a struggle.

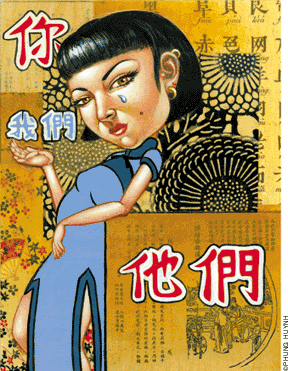

To be biracial, to be a hapa (a Hawaiian word which originally meant half-white and half-Hawaiian but now includes all people of partial Asian descent), is to be forever on the brink of two cultures. It means standing wistfully at the edges of conversation that flies by too quickly for you, since your parents spoke only English because it was the only common tongue. It means sitting in a restaurant in Chinatown feeling large-boned and ill and out of place, drinking cup after cup of oolong tea and hoping the waitress won’t bring the bill by while your mother is in the bathroom. Being a hapa means feeling forever uneasy, no matter where you are or who you’re with, white or Asian. You are always the outsider. You are always the one pretending to belong.

Though most states had active antimiscegenation laws, in 1880 California became the first state to specifically prohibit the issuance of licenses for marriages between a white person and a person of “Negro, mulatto, or Mongolian” descent. The perceived need for a ban against interracial marriages was soon replaced by the enactment of even more biased laws limiting or prohibiting immigration to the States. Not until the 1965 Immigration Act did quotas based on national origin cease altogether. And as for laws prohibiting the intermarriage of Caucasians with those of “Mongolian descent,” it was not until 1967 that the Loving v. Virginia Supreme Court case ruled antimiscegenation laws unconstitutional. The last antimiscegenation laws in the U.S. were only officially lifted in 1998, in Alabama. Until five years ago, my existence was illegal in that state.

With such a backdrop of suspicion and bias, it seems more amazing yet to see a new generation of biracials emerging from the current crop of youth—and seeking identity. And it is notable that almost all Asian-Caucasian biracials are young, offspring from interracial couples who met and married in the 1970s. This is particularly apparent on college campuses, where many larger universities have organizations for hapas or societies based on bi- or multi-ethnic awareness. Penn has one, a society that “seeks to increase community awareness of issues concerning mixed heritage and multiculturalism in an increasingly multicultural society.” Check One—called so in defiance of the widespread but ever more invalid instructions for determining ethnicity on many application forms—was formed in 1995 and has been growing steadily ever since.

Media portrayals of bi- and multi-ethnics are beginning to show up, as well—although they are not always greeted positively. In the recent movie Charlie’s Angels II: Full Throttle, the brainy, butt-kicking Angel Alex is revealed to be half Chinese and half Caucasian (although the actress portraying Alex, Lucy Liu, is fully Chinese). This portrayal actually caused a sizeable uproar regarding race and intermarriage—but, contrary to those many years of antimiscegenation laws, this time it came from the Asian side.

Aki Aleong, president of Media Action Network for Asian Americans, wrote an open letter to Angels director Joseph McGinty Nichol in which she protested that the biracial heritage of Liu’s character “nullifies the wonderful statement you made by casting her in the first installment,” explaining this “nullification” by saying that to “imply that [Lucy’s character is] half Asian belittles the pleasure and relief Asian Americans and fair-minded audiences had when they saw an Asian woman standing up for justice and overcoming great obstacles.”

This exchange illustrates an area of biracial life that many mainstream Americans and even Asian Americans are unaware of: the tensions that exist between full-blooded Asians and those biracials whose purity is, as one person I know put it, “diluted.”

The diluted blood referred to was mine.

It wasn’t the worst thing that has ever been said to me, and it wasn’t even truly meant maliciously, but when when a full-Asian friend jokingly e-mailed—“you better marry a nice Cantonese boy so your bloodline doesn’t get any more diluted”—I was so angry I couldn’t speak civilly to him for a week.

“THATS SO EFFING IGNORANT” I e-mailed back in furious capitals, ignoring the punctuation and grammar about which I am usually so particular. A few weeks later during Asian Pacific American Heritage Week at Penn, I wrote an article in the APAHW Daily Pennsylvanian supplement in which I outlined some of the numerous snubs I’d received from Asians who, unwittingly or not, made racist remarks about whites. There were jokes about Caucasians being unable to “get” Asians, at the end of which someone patted my shoulder and said consolingly, “Don’t worry, we consider you Chinese,” or the freshman boy I knew who was disappointed at the number of white people in his dorm. “Who am I supposed to be friends with?” he moaned. Once, in the English House dining hall, five or six people carried on a half-humorous conversation about the “white male/Asian female phenomenon,” complete with animated arm gestures and the punch line, “They’re stealing our womenfolk!” while Leah Banewicz, a half-Korean girl from Nevada, and I sat quietly together and thought about our parents.

There are some Asians for whom it will never be enough that I like Chinese food or have a Chinese mother. For them, even if I did speak Mandarin like a Beijing native, it wouldn’t matter because there is something inherently inferior about having fan-gwai blood, the blood of the white ghosts.

In late October I was hurrying past Pottruck Gym when my hapa radar went off. Normally I don’t talk to people handing out flyers, but the young man was tall and dark-haired and clearly half-something, and it was just one of those things, those sparks. He caught my eye and I caught his and then we were talking casually while I looked at a little paper he’d given me. He was promoting a new student organization that met to talk about issues like race and faith in modern America, which of course interested me. He gave me a card and wrote his name on the back and I promised nonchalantly to come to a meeting sometime soon.

As we were about to part he asked, “Hey, so what’re your halves?”

It was love.

“Chinese and German. What about you?”

“I’m half Korean and half Dutch. I thought you were when I saw you.”

When I left I smiled as bewitchingly as I knew how, crinkling the corners of my eyes to max my Asian appeal. I was going to go to the first possible meeting, I was going to get to know him, I was already planning our first date.

When I got home I checked out his organization, CARP, online, and found out that it was the “evangelizing student division” of Unification Movement. The one headed by the Reverend Sun Myung Moon, who thought he was the second incarnation of Christ; the cult movement known fondly, in fact, as the Moonies.

I’d like to say that then, throwing the flyer into the trashcan next to my desk, is when I had an epiphany about what it means to be biracial, that I realized then that race doesn’t matter and personal identity is actually found in things other than bloodline. But of course one doesn’t have such realizations all in a saccharine burst. Also it’s not true: I haven’t found that race is irrelevant. It’s still a question that defies the boundaries I’ve tried to force upon it.

I have learned, am learning, to believe that I will never solve the search for moorings and a fixed identity; but somewhere along the way, sometime after the high-school poetry of aloneness and before the encounter with my Moonie soul mate, the fervor and clamor has calmed. Perhaps that’s why, though I wanted to start so fiery and end so fierce, with condemnation or earth-shaking understanding, I can only acknowledge that the search for identity, the search for commonality, has evolved into the search for the ability—not to understand but to recognize, to respect—what it is between you and us and them.

Alison Stoltzfus C’05 is an English and communications double-major from Ashburn, Virginia, and a work-study student at the Gazette.