Nearly two centuries ago, Penn professor Henry Hope Reed put William Wordsworth on America’s cultural map. More or less forgotten today (make that more), Reed was an impressive scholar whose enthusiasm for Wordsworth and English Romanticism helped shape the nation’s literary values. At a time when most schools barely acknowledged contemporary literature, he also played a role in the University’s rebound from its early 19th-century “Low Water” mark.

BY PETER CONN

Penn’s oldest surviving university catalogue is an eight-page pamphlet published in 1825. Unlike its modern descendants, this venerable document contains neither course descriptions, nor a specification of requirements, nor the college rules (if there were any). Following a list of the 25 trustees, the catalogue provides only the numbers of students, and the names of the University’s 17 professors, divided into the categories of “Arts” (three faculty members), “Medicine” (seven), “Natural Science” (five), “Law” (one), and “General Literature” (one). Three non-professorial teachers are identified (one each in French, German, and Spanish), and the tally concludes with the janitor, William Dick.

The Medical Department was thriving: 484 students had attended classes that year. The undergraduate college, on the other hand, was doing rather less well. Just 16 men graduated from the “Collegiate Department” in 1825—about the average number of graduates for the previous 15 years. The small size of the class was a sad but accurate indicator of the college’s early 19th-century decline. So, too, was Penn’s first printed library catalogue, published in 1829. It recorded that, 80 years after the founding of the University, the library owned only 1,670 volumes, comprising 884 titles. Not surprisingly, the fifth chapter of Edward Potts Cheney’s 1940 history of the University, which reviews those decades, is titled, “Low Water.”

The Arts graduates of 1825 included 17-year-old Henry Hope Reed, the son of lawyer Joseph Reed, Jr., and the grandson of Joseph Reed, who had served as George Washington’s adjutant during the Revolutionary War. Henry, a young man “remarkable for his indifference to the athletic games in which his comrades delighted,” was named the Latin Salutatorian for his class, a forecast of the academic distinction he would go on to earn.

In 1831, after practicing law unhappily for a few years, Reed returned to Penn as “assistant professor of moral philosophy, having charge of the Department of English Literature.” Four years later, the Trustees elected him to the Professorship of Rhetoric and English Literature, a position they had designed for him. The combination of Reed’s assignments perfectly matched his own conception of his academic role: What he considered a moral imperative informed all of his teaching in language, literature, and history.

From the beginning of his 20-year teaching career, Reed championed the poetry of William Wordsworth, ranking him, along with Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare, and Milton, as one of “the five poets of the highest order.” While that judgment would not find much support today, Wordsworth continues to command a central place in the history of English poetry.

In teaching the poetry of Wordsworth, or indeed any contemporary literature, Reed was something of a pioneer. “I doubt many American colleges or universities of the 1830–1850s era were devoting faculty positions and courses to the serious study of literature,” says John Thelin, a professor of higher education and public policy at the University of Kentucky who is a leading authority on the history of higher education in America. “Most of the colleges were following the Yale Report [of 1828] and tended to have no ‘majors’ and a fairly tedious classical curriculum,” in line with the document’s defense of a traditional course of study built around Greek and Latin. “So, the fact that Penn would hire and allow a professor to teach English literature, including the poetry of Wordsworth, suggests a very distinctive university. Way ahead of the curve.”

Reed’s enthusiasm for Wordsworth’s poetry expressed itself most influentially when, in 1837, he edited and published The Complete Works of William Wordsworth, the first one-volume collection to appear on either side of the Atlantic. (Wordsworth, motivated both by pride and by a keen desire to enhance his income, had been hectoring his own English publisher to bring out such an edition, without success.)

A little over a year after his edition appeared, Reed published an anonymous and quite favorable commentary on the book in the New York Review. (Anonymous and friendly self-reviews occupied a sizable place in early 19th-century criticism.)Much of Reed’s 27,000-word essay is given over to establishing his high claims for poetry among the arts and for Wordsworth among the poets. At its core, Reed’s conception of poetry’s value is more theological than aesthetic: “The highest poetry must be sacred,” exhibiting “for its own glory … its affinity and subordination to religion.” Wordsworth, Reed contends, more successfully than any other modern poet, has, through his verses, made “strenuous and constant efforts for the spiritual elevation of mankind.” While this is not the sort of vocabulary that later critics would deploy in their assessments of Wordsworth, it seems to have stimulated a wide appreciation of the poet among antebellum readers.

Wordsworth was by no means unknown in the US prior to Reed’s edition of his work. An American edition of Lyrical Ballads had been published in 1799, just a year after this landmark volume appeared in England, and other editions followed. Furthermore, over the first three decades of the 19th century, a number of American poets had made their Wordsworthian loyalties clear.

To cite the most striking example, William Cullen Bryant, America’s first major Romantic poet, responded to Wordsworth with an emotion akin to reverence. William Henry Dana, author of the classic memoir, Two Years Before the Mast, reported that “I never shall forget with what feeling my friend Bryant … described to me the effect produced upon him by his meeting for the first time with Wordsworth’s ballads. He said that, upon opening the book, a thousand springs seemed to gush up at once in his heart, and the face of Nature, of a sudden, to change into a strange freshness and life.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson traveled to England in 1833, pilgrim-like, to meet Wordsworth and Coleridge. Arriving unannounced at Rydal Mount, the Wordsworth family’s cottage in the Lake District, Emerson was received with courtesy and spent several hours in a conversation that ranged from nature to education to politics. Along the way, Wordsworth did not disguise his rather low estimate of Emerson’s fellow Americans: “I fear that they are too much given to the making of money, and secondly, to politics.”

Emerson left Rydal Mount with a somewhat diminished admiration for the man he had traveled several thousand miles to meet. Nonetheless, Wordsworth’s influence can be detected across much of the Emersonian canon, including his immensely consequential essay, Nature, which would appear in 1836, just three years after his English sojourn.

Bryant and Emerson typified a fervent appreciation of Wordsworth’s poetry but one that was embraced by a fairly narrow coterie of literary practitioners. Scholars who have examined the question of Wordsworth’s reputation in America have concluded that it was through Henry Reed’s “interested efforts”—his 1837 edition of the poems and his 1839 essay, in particular—that “Wordsworth was first made widely known, and admired, in this country.” This conclusion was first ventured more than 90 years ago by Annabel Newton, in her book, Wordsworth in Early American Criticism; most writers on the subject in the subsequent nine decades have agreed.

Note that the aging and pious Wordsworth whom Reed celebrated in his lectures and essays was quite a different poet from the 20-something radical who had, nearly four decades earlier, famously welcomed the coming of the French Revolution:

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very heaven!

That youthful dream of heaven quickly evaporated. As he watched the Revolution collapse into the Terror, Wordsworth’s allegiances shifted irreversibly toward a reverence for the status quo, both in politics and religion. Edmund Burke, the towering defender of conservatism against revolutionary change, became the poet’s most important intellectual mentor.

Although Reed’s allegiance embraced the entire Wordsworthian canon, it was anchored primarily in his affinity for the later work, in which the poet affirmed the values of Christian piety and social order.

In 1836, while Reed’s edition was still a work in progress, he opened a correspondence with Wordsworth that continued until shortly before the poet’s death. In all, the two men exchanged 71 letters that fill well over 200 pages in the printed edition. Here lies another of Reed’s distinctions. It is surely safe to claim that no other 19th-century American academic carried on such a volume of communication with a major English poet.

It would be gratifying to report that these letters are filled with elevated literary talk and biographical insights, seasoned with dollops of titillating gossip, all in memorable prose on both sides. Instead, they reveal a tug of war between an importunate admirer and an aging and—initially, at least—reluctant interlocutor. The ratio of letters and pages signals the imbalance in the correspondence: Reed wrote 48 of the letters, accounting for 175 printed pages; Wordsworth wrote just 23 letters, totaling 63 pages.

From the outset, Reed adopted a tone marked by an unctuous flattery that barely conceals an almost audible need for the poet’s attention. In the first letter Reed sent, on April 25, 1836, he introduces himself in fulsome terms. His letter, he assures Wordsworth, is not intended to flatter but to express “the flow of gratefulness, which so naturally gushes” whenever he re-reads one of the great man’s poems. He discloses a prompting “sense of obligation”: communing with these poems, he confides, “I have felt my nature elevated.” Reed closes by pronouncing “blessings” on his idol.

What Reed did not tell Wordsworth was that he had already completed most of the work on the edition he would publish the following year. Soon after he received the book, Wordsworth wrote to Reed on August 19, 1837—16 months after receiving Reed’s first letter. Although he briefly declared himself pleased to learn of the wider circulation of his work, Wordsworth devoted most of his letter to complaints about the lack of copyright protection. In the absence of legislation protecting the publications of British authors, Wordsworth writes, American publishers inevitably succumb to the “temptation” to issue cheap and shoddy re-prints, sharing none of their ill-gotten proceeds with the authors whose work they are effectively stealing. (Charles Dickens was only the most famous and most voluble of the writers who frequently made the same accusation. In the event, the protections of copyright were not extended to British authors until 1891.)

These first two exchanges between Reed and Wordsworth anticipate the competing emphases of much of the correspondence: Reed pelting Wordsworth with repeated and effusive compliments, the poet more interested in his sales and lost income, along with the losses he had suffered by investing in several American companies. In a letter dated July 18, 1842, Wordsworth declares that, because of the money troubles he was experiencing, “nothing would tempt me to trust any portion of my little Property to an unqualified Democracy.”

Several of Reed’s letters combine salutations with advice and suggestions, some of which Wordsworth accepted. The most significant recommendation was in a letter Reed sent on April 28, 1841, in which he proposed that Wordsworth add to his Ecclesiastical Sonnets—a long sequence celebrating the history of the Anglican Church—verses carrying the story into the New World. By including “the transmission of the spiritual functions of the Church of England to the daughter Church on this Western continent,” Reed argued, Wordsworth would complete his narrative with a gesture of “moral sublimity.”

In relatively prompt response, Wordsworth mailed three sonnets to Reed, gathered under the heading, “Aspects of Christianity in America.” The three poems are titled “The Pilgrim Fathers,” “Continued,” and “Concluded—American Episcopacy.”

Here is the sestet that closes “The Pilgrim Fathers”:

Men they were who could not bend;

Blest Pilgrims, surely, as they took for guide

A will by sovereign Conscience sanctified;

Blest while their Spirits from the woods ascend

Along a Galaxy that knows no end,

But in His glory who for Sinners died.

As those lines suggest, these verses do not add much to Wordsworth’s body of work, either in bulk—he wrote over 500 sonnets—or in quality. For his part, though, Wordsworth thought enough of them to include all three in his next collection, a volume called Poems, Chiefly of Early and Late Years. In any event, the significant point is that the three sonnets earned Henry Reed the rare if not unique distinction of having more or less commissioned bespoke poetry from one of the most important literary figures of the 19th century.

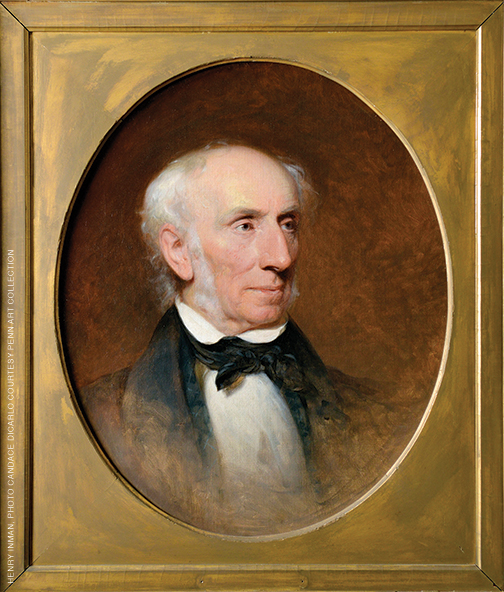

Reed and Wordsworth never met. Each time Reed began to contemplate an Atlantic crossing, the obligations of teaching and the needs of his family intervened. To ameliorate his lingering disappointment, Reed persuaded Henry Inman, an important painter of portraits and landscapes, to journey to Rydal Mount and complete a portrait of the 74-year-old Wordsworth, now Poet Laureate. In just nine sittings, Inman produced a likeness that Wordsworth called the finest of the 27 for which he had posed. Without Henry Reed’s intervention, this compelling image of Wordsworth in his old age, now in Penn’s collection, would never have been created.

Along with the portrait, Inman also produced several sketches of Rydal Mount, one of which he later used as the basis for an oil painting. Two figures, identifiable as poet and painter, stand in front of the cottage.

Wordsworth died in 1850. Four years later, Reed finally organized a trip to Europe. Since his wife was ill, his sister-in-law, Anne Emily Bronson, accompanied him. They traveled widely, in Great Britain and on the Continent. Reed sent extended and excited reports to his family about the ancient castles and churches he and Bronson visited. But he found his greatest satisfaction in the quiet days he and his sister-in-law spent at Rydal Mount, where Wordsworth’s surviving family hospitably entertained them.

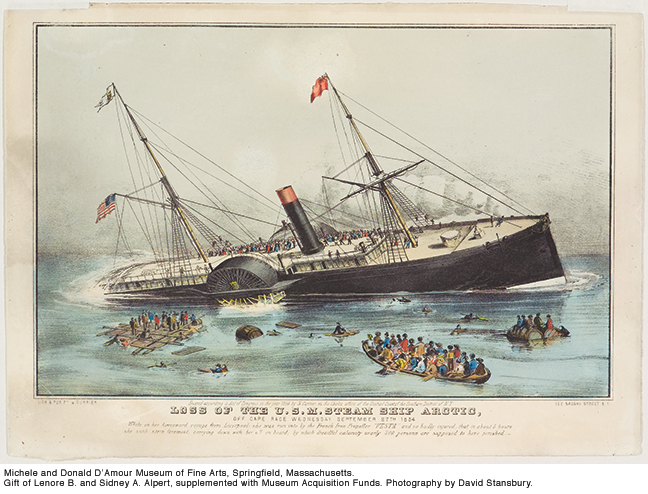

After four months of travel, Reed and Bronson boarded the S.S. Arctic in Liverpool for their return to the United States. On September 27, 1854, both were among the more than 300 men, women, and children who drowned when the Arctic collided with the S.S. Vesta and sank off the coast of Newfoundland. The shock of the disaster—one of 19th-century America’s most calamitous naval accidents—was compounded by the news that none of the several children aboard had survived, while dozens of crewmen had abandoned the passengers and commandeered the lifeboats.

Henry Reed’s death at the age of 46 was widely mourned by his family and his large circle of friends in Philadelphia. A long, admiring obituary was entered into the minutes of the American Philosophical Society, to which Reed had been elected in 1838.

Beyond that, Reed’s death impelled his brother, William, to undertake a memorial labor that would encompass another of Reed’s distinctive accomplishments, this one posthumous. Along with his work as an editor (of Thomas Arnold and Thomas Gray, as well as Wordsworth), Henry Reed had published only a number of rather miscellaneous essays in his lifetime. William gathered the copious notes his brother had written for his classes and for his public lectures, which had attracted hundreds of Philadelphians. Over the next several years, William transcribed and published several volumes under Henry’s name, among them Lectures on English Literature, from Chaucer to Tennyson and Lectures on English History and Tragic Poetry as Illustrated by Shakespeare , both of them reaching to more than 400 closely printed pages.

These transcribed lectures represent a relatively rare and important set of documents in the history of higher education in the United States. The archives of antebellum colleges house scatterings of notes taken by students as they sat in their courses at Princeton, Harvard, Yale, and other institutions. However, few copies of the lectures, as written by the professors themselves, have survived. (Sermons, on the contrary, were regularly transcribed and published.) If Reed had lived long enough to retire, he would probably have done what most early 19th-century professors apparently did at that point: discarded the lecture notes that he had been writing and revising for 20 years.

Beyond their sheer survival, what do the lectures in these volumes reveal about the content of Reed’s courses? While he comments from time to time on the specifically linguistic qualities of the writers he includes, Lectures on English Literature is drenched in Reed’s Christian piety. His focus remains fixed on the moral and spiritual qualities of each writer’s work. Thus, the “poetry of Chaucer is distinguished for what is an inseparable quality of all high poetry, its genuine and healthy morality.” Spenser’s Faerie Queene is, above all, “the great sacred poem of English literature.”

In Byron’s verses, on the other hand—Reed here predictably deducing his literary judgments from his horror at the poet’s behavior—he finds “disease, deep-seated, clinging disease. You search in vain for a single healthful impersonation of humanity; all the creations are hollow images, with no life or heart in them.” Apparently, Lady Caroline Lamb was right: Byron was “mad, bad, and dangerous to know,” or even to read.

Not surprisingly, Wordsworth receives the highest praise. His “genius” transforms his poetry into “a ministry of wisdom and happiness, both in the homely realities of daily life, and in the deepest spiritual recesses of our being.” Reed’s lectures on poetry, in short, disclose his affiliation with the religiously tinctured, earnest, and idealizing convictions of much mid-19th-century literary commentary.

Lectures on English History and Tragic Poetry is an ambitious and learned undertaking. Reed’s chapters survey the history of England from the 14th to the 16th centuries, relying on Shakespeare’s plays as infallible guides to the character and motives of the kings, noblemen, and even the commoners of the period. Reed’s procedure is out of date, to be sure. Modern scholarship has labored to excavate the historical contexts that illuminate Shakespearean drama. Reed, once again reflecting the critical tendencies of his time, depends on Shakespeare to illuminate history. At the same time, the lectures reveal an astonishing command of Shakespeare’s texts and are punctuated by many useful local insights. In other words, whatever its contemporary irrelevance to literary historians, English History and Tragic Poetry offers an underappreciated but uncommonly interesting example of antebellum American education and taste.

I mentioned earlier that Edward Cheney titled the fifth chapter of his Penn history, which ends Part Two of that volume, “Low Water.” Part Three, which documents a turning point in the 1830s, is entitled “The Renaissance.” Under the leadership of a new and stronger provost, William DeLancey (the senior officer, since Penn had no president at the time), a number of new faculty were recruited. These included accomplished scientists and scholars, whose combined contributions quickly moved the College forward. Along with the gifted mathematician Robert Adrain; the classical scholar Samuel Brown Wylie; and Alexander Dallas Bache, Benjamin Franklin’s great-grandson, who made important contributions in physics, Cheney calls particular attention to Henry Hope Reed, “whose gifted mind is attested alike by tradition and his own literary remains.”

Peter Conn is the Vartan Gregorian Professor of English Emeritus and Executive Director of the Athenaeum of Philadelphia.

A wonderful recounting of a great Penn professor by one who also stands high in the firmament of the University’s outstanding scholars.