Class of ’70 | Carl Harrison Gr’70 learned from an early age that spreading the Word is not for the faint of heart. He was only five years old, and living in North China with his missionary parents, when the Japanese invaded in 1939. Not yet ready for kindergarten, he was home with his parents on the day Japanese troops seized the local school and dragged his brother and sister from their classroom—imprisoning them for the remainder of the war in a military internment camp.

The Harrisons fled China in 1944, and returned to the small town in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania where Carl had been born. He did not see his brother or sister again until 1945.

They remained, however, a family of faith; Carl maintained his determination to become a missionary. He went on to study at the Philadelphia Bible Institute (now Philadelphia Biblical University), then transferred and earned his B.A. in English literature from Wheaton College in Illinois in 1957. A year later, Harrison attended an information session for Wycliffe International, an organization of Bible translation missions.

“You think of a missionary as someone who preaches, but that’s not my gift,” Harrison says with a self-deprecating chuckle. “I knew that. Then I discovered this mission where they almost discouraged that. [Wycliffe] didn’t want us to be traditional, ‘preaching-type’ missionaries. We were scientists, doing language analysis.”

Harrison met his wife, Carole, during his training session with Wycliffe’s affiliate organization, SIL (formerly the Summer Institute of Linguistics), in 1958, and they soon married. In January of 1960, with their infant son bundled in tow—much the same way Carl himself first left the country, on his way to China with his parents—they embarked on a 10-day sea voyage to their first mission among the Assurini, a small indigenous tribe of the Brazilian Amazon.

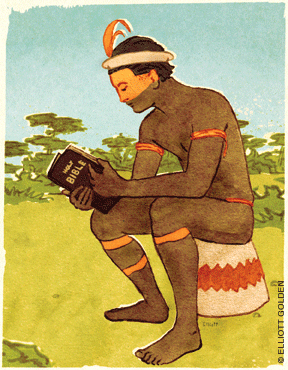

They stayed for five years, raising their firstborn and another two children in this village of several dozen Amerindians. There Harrison’s passion for the written word, once satisfied by his study of English literature, transformed into an urgency to liberate indigenous tribes from sociological and spiritual marginalization with the power of literacy—and the Gospel.

“These native tribes of Brazil were looked down upon by their more civilized neighbors, told they don’t have a real language—that they’re just grunts and groans, ‘monkey talk,’” Harrison explains. “They’d often been made to feel more like animals than humans.”

Upon his return home in 1965, he applied to Penn’s graduate linguistics program, then under the helm of its legendary founder Zellig Harris C’30 Gr’34. Harrison went on to complete both his master’s thesis and doctoral dissertation on the syntactical aspects, morphology, and phonology of the Assurini language.

While he was still writing his dissertation, Harrison and his wife and three children moved back to Brazil in 1969. This time, they joined the Guajajara—another indigenous Brazilian tribe and language group living in a cluster of villages approximately 500 miles southeast of the port city of Belém. The Guajajara speak a language distinct from but closely related to the Assurini tongue Harrison had studied in previous years.

Resuming a colleague’s previous original linguistic analysis of the tribe, and thanks to the similarities between Assurini and Guajajara (“It’s like if you wanted to learn French, and you already knew Spanish,” he explains), Harrison was fluent in Guajajara within six months. He then set about translating into Guajajara the bestseller known as the Christian Bible.

He began, as most missionary linguists do, with the New Testament. A rough draft of Mark came first and took a year to complete. Group Bible studies and reading instruction began immediately thereafter.

Harrison then spent the seven years between 1971 and 1978 doing very little besides translating the nearly 150,000 words of the New Testament. It took another seven years, in partnership with local consultants and native speakers, to complete the edits necessary to ready the manuscript for publication. The Guajajara New Testament was printed and distributed in 1985.

Harrison believed his work was done, and moved on to other projects. He spent much of the late 1980s and early ’90s as he had the early ’60s—training Brazilian missionaries alongside his wife and serving as an adjunct professor and graduate advisor at the University of Brazil (which has since been renamed the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro) and the Federal University of Pará.

Harrison was the first to teach generative-transformational grammar in a Brazilian university. “Almost all of the first batch of Brazilian linguists from the ’60s were students of mine,” he reports. By the end of his teaching career, Harrison’s students had begun referring to him as “Brazil’s Father of Modern Linguistics.” He thought he’d reached the pinnacle of his groundbreaking career as a linguist. Then, in 1995, he realized his mission was not quite completed.

“The pressure was on, from members of the Guajajara and other missionaries who were working with them,” Harrison recalls. “They said, ‘When are you going to do the Old Testament?’ I was already 61 then. I said, ‘Never.’” He pauses and laughs before continuing: “I finally said, ‘Okay, I’ll give it a try. But I better get going on it, ’cause I’m getting kinda old.’”

Harrison dove into the translation in 1996 and worked at a breakneck pace. He awoke each morning at 4:30, kept interruptions minimal, and finished a rough draft of the Old Testament—which, at nearly 600,000 words in the original Hebrew, is almost four times as long as the New Testament—in four years. (“Probably a record,” he says.)

The subsequent edits to prepare the manuscript for publication took another seven years; the Guajajara tribe conducted a lively dedication ceremony across several villages and over the course of three days in early October 2007.

All told, Harrison’s translation project spanned 25 years. In a series of missions and furloughs, the Harrison family lived 30 years among the Guajajara—years rife with great accomplishments as well as great challenges, not the least of which were several bouts with serious illness.

“If doctors were to test me, they’d discover a new blood type,” he quips. “I’ve had malaria, typhoid fever, hepatitis, meningitis … just to name a few.”

Other roadblocks surfaced from the most basic of cross-cultural differences. For example, the Guajajara do not have words for camel or sheep—two animals that appear with some frequency in the Bible.

But, as Harrison explains: “You find a solution. You show them a picture and you tell them what the animal is like, and they come up with the word. They came up with several words for camel, and we finally picked a phrase that everyone seemed to think was best. It was: ‘horse with a wavy back.’”

Today, the Guajajara are on the verge of becoming a literate society. They write letters to one another, and have started a small community newspaper.

“And they literally wore out those original New Testaments, the ones we had printed back in 1985,” Harrison reports. “We had to publish a new batch.”

Harrison is by no means unique in parlaying his graduate linguistics education into a Bible translation ministry. Indeed, a significant segment of the linguistics community is comprised of missionaries who seek to bring the Bible to new language groups.

According to the most recent United Bible Societies’ World Report, portions of the Bible have been translated into 2,454 languages—an impressive number but still well under half of the estimated 6,912 languages still spoken in the world today.

And very few missionary linguists are successful in translating the Bible in its entirety. In the case of complete translations of both the Old and New Testaments, the world’s total shrinks to 438. Within Harrison’s mission field, Brazil, the number dwindles further. Of the country’s estimated 188 living languages, portions of the Bible have been translated into almost 40, but the entire Bible had only been translated into two. Now, thanks to Harrison, there are three.

For the Guajajara, Harrison’s translation project has illuminated their understanding of their tribe’s unique identity and voice.

“The tribe has had contact with outside civilization for over 300 years,” notes Harrison. “They were first contacted in the 1600s. So they’d seen books; they just didn’t know how to read them.

“They had no idea they could write their own language, or that they had a ‘real language’ at all. When they found out they could, it changed their whole view of things … all of a sudden they developed this pride in their language. Everyone wanted to learn how to read it. And now, most of them have.”

—Rachel Estrada Ryan C’00