A century ago the Morris family drained the lower meadows of their bucolic summer estate in order to graze cows. The recent restoration of this wetland—along with two related projects on the tract it occupies at the Morris Arboretum in Chestnut Hill—has drawn a wide range of visitors, from schoolchildren sloshing around in rubber boots to professional land managers.

The snakes, birds, and frogs seem to like it, too.

“With nature, it’s either acceptable or unacceptable,” says Kate Sullivan, director of marketing for the arboretum, which today is operated by Penn as a public garden and educational institution. “This whole area has become so much more attractive [to wildlife].”

The returning wetland is part of a larger effort, known as the Papermill Run Riparian Restoration Project, that includes restoring the stream bank along Papermill Run and creating models for storm-water management on the hillside and in an adjacent neighborhood. In the latter project, runoff water that would otherwise get pumped directly into the creeks now travels into a series of underground drains that slowly release it back into the environment. The exhibits are meant to be a teaching tool not just for engineers or professional land managers, but for private homeowners.

More likely to draw the attention of the average visitor are the colorful trees and shrubs planted along the stream near the arboretum’s entrance—all native to Pennsylvania, such as winterberry holly and red twig dogwood. In addition to their aesthetic appeal, they also help stabilize the soil.

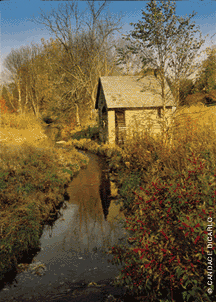

Before the stream-bank restoration, the arboretum was in danger of losing a historic pump house due to erosion. Papermill Run also was carrying a large amount of mud- and pollutant-filled water downstream to the Wissahickon Creek, which feeds into the Schuylkill River, according to chief horticulturist Vince Marrocco. To address these problems, he says, they sculpted the banks back to create a gentler slope that would lessen the impact of the flow downstream; planted water-tolerant plants with massive root networks to help stabilize the stream edge as well as absorb pollutants; and laid cocoa-fiber logs along the banks to anchor and nourish the plants.

Wildlife have expressed their immediate approval of the creek and wetland projects, according to Paul Meyer, the F. Otto Haas Director of the arboretum. “Great blue herons and eastern bluebirds and red-winged blackbirds—they all moved in and almost instantly made themselves at home.”

Meyer says he was also amazed at how quickly the wetland filled in, transforming from “a mud puddle” to a “beautiful floodland.” As such, it fits in well with the arboretum’s offerings. “This is not only a museum of plants, but it’s a museum of different kinds of landscape systems. If you want to learn about formal rose gardens, we’ve got one; if you want to learn about wetlands or meadows, we’ve got that, too.”

—S.F.