Thomas Adams Calvert was coming home.

By Sarah Richter

Up until that point in my 16 years of existence I had never made an old man cry.

His name was Donald Skelton. He was 85 years old. I had never met him before, but I listened patiently to his frail voice across miles of phone line, knowing that I had no magical words to wipe away his suffering. So I told him everything, from the beginning: how in the world I had come to possess a portrait of his brother, smile suspended in chipping, brittle paint, a flash of life captured only months before he died as a soldier in World War II.

It was an unlikely story. My Uncle Vinson had gone to my grandfather’s former jewelry store, on Lincoln Avenue in Miami, to investigate some family history. The new owners mentioned in passing that he must have left something up in the attic. Perhaps we wanted it back.

They led Vinson upstairs. There he found them: young men in uniform—foot soldiers, pilots, sailors, generals—70 portraits, each a foot and a half long and 10 inches wide, all in the same muted palette of flesh tones and dappled light. Almost all were smiling. When the owner laughed that his wife thought the paintings were haunted, my uncle took them without hesitation.

On the ride home, he called my grandfather to verify. Yes, the portraits were his. After the war an artist had been commissioned to paint the likenesses of 200 Miami boys who had died in combat. They were destined for a downtown memorial, but somewhere along the line the project was abandoned; people were eager then to forget the war. My grandfather was not. He offered to store a few of the paintings until the town decided what to do with them. So the 70 soldiers had smiled through layers of dust for almost 60 years.

They became a mission for my uncle, who drafted my father and me to carry out his plan. We were to return the portraits to their families—to send them, at long last, home.

At first this task seemed easy. The artist had scrawled the name of each soldier on the back of his portrait, and each man was decorated in accordance with rank or division. A quick search of the World War II registry could shed some light on living relatives. We could just Google the rest.

“See?” my uncle exclaimed as he closed out of the registry website, eyes gleaming over his laptop. “This won’t be hard at all!”

Three months, 20,000 Google searches, and only a half a dozen returned portraits later, I couldn’t help but disagree.

I would have stopped. It didn’t seem worth it. The registry was outdated; paper trails had blown away. The artist had terrible handwriting, which often meant a dozen possible spellings of a single soldier’s name. Even when we got that far, half the people we called had no idea what we were talking about. Hadn’t even heard of so-and-so. Family members were dead, phone lines off the hook, letters returned unread. A lot can happen in 60 years.

These doubts were compounded by my own growing sense of dread. My uncle and father had deputized me to call the family members. But what seemed to be standard secretarial work was something much more emotionally complex. How do you call a complete stranger and explain that you have an image of their brother, their husband, their father, exactly as they saw him last, over 60 years ago?

Most people reacted with shock. Disbelief. Many asked if we were trying to sell them something, or if we were playing a practical joke. Who was I, some bored teenage girl with nothing better to do than inflict more suffering on harmless old folks? But then, after much cajoling, frustration gave way to suspended skepticism. Skepticism ebbed into curiosity. Curiosity crept its way into wonder. And from wonder, well, there were tears.

Donald Skelton told me everything that he remembered about his brother. William Osbourne Skelton had been working his way through professional school when he signed up for the Navy. Donald was his junior by many years, far too young to comprehend the gravity of the war, much less enlist. To this day, he doesn’t remember how or when or where his brother was killed in action—only the silence that descended upon the household when his mother received that letter. But Donald Skelton was happy that we had called him that day. Somehow, it seemed to rectify pieces of the story that didn’t seem right before.

Some people called it fate. One woman, whose grandfather we returned to her, wrote back saying that she had heard of the old jewelry store. Her mother had bought something decades ago, and for some reason had never thrown away the grey suede box embossed “Richter’s Jewelry.” “I know now why I kept it,” read her thin handwriting. “Somehow life always falls into place.”

Another woman asked that we mail a portrait of her great uncle to Kentucky as soon as possible; her aunt was turning 90 early the next week and she could think of no gift that would be more meaningful. We heard from the woman soon after. She said that all her aunt could do was hold the portrait in her hands and cry.

Some of the 40-odd family members that we tracked down did not want the portraits back. After the shock had worn off, many told us to donate it (“Where?” “Somewhere, anywhere. Just donate it.”). Others wordlessly hung up the phone. One woman succinctly stated that she just didn’t want the portrait of her uncle, delivering the words as one might tell a telemarketer to remove this number from the calling list. I often wondered what they felt after hanging up the phone. Where did they place their hands?

I felt Donald Skelton’s breath rattle on the other end of the receiver. For a long time, we said nothing.

Almost four years have passed since that day. I sat down to write this essay, and finished it. I thought my job was done. There was a strange sense of finality in typing those last few lines. But I was wrong. The portraits were not done with me.

In March I was initiated into Delta Phi, a co-ed fraternity also known as St. Elmo that has a rich and complex history spanning back to 1849. Brothers have fought and died in every war from the Civil War to Vietnam, and plaques around the house commemorate the losses. As new members, we were “encouraged” to memorize those names. They are there for a reason, brothers have told us. It is our history. Know it.

It was a chore—yet another mental exercise whose purpose was to drain the pledges’ lives of both time and fun. My pledge brothers and I reduced the names to mnemonic devices so that we could regurgitate them back on command. But after a while I started feeling guilty about the shortcut. History should be important. So I turned my eyes towards the engraved words above the fireplace downstairs and actually read it, not as an assemblage of words but as an actual memorial.

In memory of those members

of Eta chapter Delta Phi

who gave their lives.

World War II

(1941-1945)

Thomas Adams Calvert

Howard May Jr

Caleb Milne IV

Samuel Felton Posey

Robert Woodman Rose

Peter VanPelt

These were my brothers who had died in the war. They walked the same halls as I did, wore the same symbols, learned the same history. And for a passing moment, one of their names felt familiar.

Thomas Adams Calvert.

I sounded the letters out in my head. Calvert. It was a strange name, not like Brown or Jones or Robinson. Calvert. How many times in a lifetime does one hear that name? But it sounded right. I looked him up in the World War II registry, a place I had not visited in years. He came up immediately, and two words pushed my heart down to my stomach: Miami Dade.

I told myself to keep calm. What were the chances? Five hundred men from Miami Dade died in the war; 200 had been painted for the memorial. We had 70 portraits, and returned around 40 of them. Had our paths crossed?

I called my father. Yes, the name sounded slightly familiar. We conference-called my uncle, who, to this day, keeps all of the files and portraits in his office, and he told us he would double check. “It sounds familiar, to say the least,” he said.

Five minutes later my phone rang. My uncle’s voice betrayed an excitement that I recognized all too well. Thomas Adams Calvert was one of the portraits. We had never found his family. At that very moment my uncle had him in between his hands.

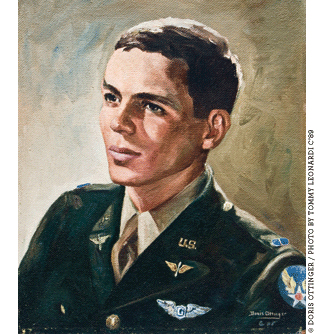

Thomas Adams Calvert was in the Air Force. He had short dark hair, high cheekbones, and delicately set eyes. He looked proud, and dashing. And he would arrive through rush mail two days later.

That night my father had asked me if a frat house was the right place for him. Beer pong and flip cup do not seem like honorable activities for the memory of a life and death of that magnitude. “You know,” he mused, “I’m sure the graduate board of your fraternity had some sort of dialogue with Thomas’ family in the months after he died. They may even keep tabs on them now. With that information, we might be able to track down his living family members.”

I thought about it for a moment. He was right. We could finish the job we started.

Then I explained to my father something that through my initiation into the house I had failed to understand. If Thomas Adams Calvert were to be hung in the house, I would walk by him every day for the next three years. And if the frat house is my home, and my brothers are my brothers, then we were his family after all. He didn’t belong anywhere else.

Thomas Adams Calvert was coming home.

Sarah Richter is a College sophomore and a member of Delta Phi fraternity.