Dennis Culhane’s groundbreaking studies show that most homeless people don’t fit the stereotype—and that many available programs don’t fit them.

By Meg Egan

Sidebar & Slideshow | URBAN NOMADS: A Poor People’s Movement

Photography by Harvey Finkle, SW’61

LEONA SMITH KNOWS what it’s like to hold down two jobs and still struggle to make the mortgage, the car payment, the utility bills. She once spent a winter without heat and electricity, sending her three kids to neighbors’ homes to wash up, an experience she recalls as “humiliating” for all involved. Later, with help from city agencies, Smith got her utilities turned back on; and she soon found a better job, working for a West Philadelphia tailor. She also began working with homeless people at a shelter in a Methodist church — a situation that attracted her, she says, because she understood their struggles. She quickly became a vociferous advocate, accruing an impressive list of victories on behalf of the homeless and later becoming the founding director of Philadelphia’s Employment Project.

But

none of this made her immune to homelessness herself. In the early

1990s, when too many city paychecks didn’t arrive on time, she couldn’t

pay her workers, or herself, or her bills. After she received an

eviction notice for failure to pay rent, she had to leave her apartment

and sell her furniture to make ends meet. And she found herself

homeless.

Smith

never lugged large plastic bags around in a grocery cart, and apart

from her advocacy, she would pass for an average citizen — as would the

vast majority of people staying in homeless shelters, according to the

research of Dr. Dennis Culhane, associate professor in the School of

Social Work. For Culhane, the basics of Smith’s story echo those of the

thousands who make their way through Philadelphia’s public shelter

system each year. Two of his most recent studies — “Where the Homeless

Come from: The Prior Address Distribution of Families Admitted to Public

Shelters in New York City and Philadelphia” and “A Typology of

Homelessness by Pattern of Public Shelter Utilization” — debunk some of

the stereotypes of people staying in shelters and offer straightforward

strategies for preventive services.

In

his “Typology of Homelessness,” Culhane categorizes a good 80 percent

of single adults staying in shelters as “transitionally” homeless: they

generally experience only one, relatively short (about 42 days) stay,

usually the result of some sort of catastrophe — perhaps a house fire

or job loss — and usually after spending time “doubled up” with friends

or family. An estimated 5,000 people in Philadelphia were

transitionally homeless in 1995, according to Culhane, and few of them

would stand out in a crowd.

“Most

of the people in the shelter system expend tremendous effort to make

sure that they maintain their personal appearance and hygiene, and they

don’t look different than other individuals that you would see walking

down the street,” says Culhane, who also serves as research associate

professor of psychology in psychiatry. “They don’t have a scarlet letter

that says ‘homeless.’ In fact, it’s very important for people to

maintain their identity and that they don’t adopt a ‘homeless’

identity.”

The nation’s “acute shortage of affordable housing” was recently examined by U.S. News and World Report,

which noted that about five million American households now spend more

than half their pre-tax income on housing, while some 1.2 million

Americans fit the Federal definition of “poor” by earning less than

$12,000 annually. And while advocates for the homeless offer various

explanations for how a person ends up in a shelter or on the streets —

mental illness, domestic violence, the “downsizing” of employment — the

common thread is poverty.

Back

in 1985, as a Boston College graduate student, Culhane spent some time

in Philadelphia “researching” the homeless by passing himself off as one

of them. He and a friend spent their summer eating at soup kitchens and

bunking in city shelters. Now 33, Culhane is eager to talk about his

research experiences, whether in the field or working numbers.

The

shelter system, says Culhane, has become the immediate answer for too

many problems. Don’t know where to send that guy just released from

prison? The city shelter ought to have a bed. And that couple discharged

from a mental-health facility? Send ’em over to the homeless shelter.

“It’s like the default system,” he says. Shelter administrators often

approach all clients in the same way, as if each had the same reasons

for being homeless and the same salve would cure all. Even the most

caring service providers “have just proceeded blind,” agrees Phyllis

Ryan, executive director for the Philadelphia Committee to End

Homelessness. Culhane’s research begins to make sense of that vast clump

of individual stories, his supporters say: his numbers and his

descriptors bring city shelter registers to life — and invite new

attempts at creating solutions.

Susan

Wiviott, associate commissioner for planning and policy development for

New York City’s Department of Homeless Services, says that while

Culhane’s findings include “a couple of surprises,” most of his results

support what many frontline workers already know from experience. But

experiential knowledge often doesn’t carry much weight in political

circles, where projects and plans get funded. Culhane’s numbers, Wiviott

says, “allow us to speak with authority.”

When

Culhane and his colleagues developed their “typology of homelessness”

by examining intake-data on single homeless adults compiled by public

shelters in New York and Philadelphia, they found they could break down

the population into three fairly distinct groups: “Chronic,” “episodic,”

and “transitional.”

Chronic

shelter-users make up only 10 percent of the total population, but use

up a full half of the total shelter days: that is, on any given day they

comprise half of the adults sheltered. The stereotypical homeless

person — the man in tattered clothes, drinking from a 40-ounce bottle

of beer, or the woman wearing two coats in the middle of July, talking

to herself on a street corner — would be a chronic user: some 70

percent have substance-abuse problems, 21 percent are mentally ill, and

30 percent have some sort of physical disability, according to Culhane’s

findings. Overall, about 85 percent have some health problem. Their

shelter stays tend to be very long: on average, 165 days per episode;

over a two-year period, each will spend some 252 days in a shelter.

Episodic

shelter-users comprise another 10 percent of the single-adult shelter

population; these people tend to be in and out of shelters, their stays

often punctuated by spells in drug-rehabilitation or in prison. Some 17

percent suffer from mental illness and 60 percent have a substance-abuse

problem, Culhane says; overall, 65 percent have had need for

mental-health or substance-abuse services. Culhane refers to episodic

users as the “street homeless”; about 1,100 single adults were episodic

users of the Philadelphia shelter system in 1995.

Howard,

for example, spent 15 years on the street, traveling from state to

state, sometimes staying in shelters, sometimes sleeping beneath

railroad tracks, working odd jobs and selling the occasional stolen car.

Today he lives in

a boarding house; he also attends a program — and visits with his

caseworker and psychiatrist — at ACCESS West Philly, a case-management

project for people who are homeless and have severe mental illnesses,

such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Like Howard, most of the

center’s clients have an addiction to drugs or alcohol.

“My

addiction and my illness took me to Chicago, Detroit, Boston,” says the

tall, 40-year-old black man, cradling a ping-pong paddle in his hands.

“I carried my drugs and my alcohol with me. And my insanity.” Now,

Howard plans to return to college sometime, to pursue a degree in social

work; in the meantime, he is the undisputed ping-pong champion at

ACCESS West Philly.

There

were about 5,000 “transitional” shelter-users in 1995, comprising 80

percent of the total shelter population. This group has the lowest rate

of substance-abuse problems (still high at 40 percent); 14.5 percent

have some sort of mental illness. Most lived in precarious arrangements

before becoming homeless; they tend to visit a shelter just once, after a

catastrophic event, and stay about three weeks.

“What’s

been lacking [in services for homeless people] is no one knew exactly

how big any of these populations were,” Culhane says, “and no one really

knew how to target. There hasn’t been data — agency-level data, even.”

Culhane’s research and analysis of single adults suggest that a

comprehensive, community-based approach to homelessness should be

developed, one that has specifically-targeted services and is more

streamlined than the typical “warehouse” approach.

Of

all shelter-dwellers, transitional users — the largest subgroup — are

best suited for preventive services, Culhane says. To improve their

access to and success in such programs, service providers ought to be

community-based and community-focused: offering job training, legal-aid

and health services, and housing assistance.

Many existing emergency shelter programs work for people who are

transitionally homeless, he says. “The fact that they come in and leave

very quickly is exactly what you want. That’s what the emergency system

is for: people come in, get their things together, tide them through

some emergency, and they hopefully will go back into the community.”

Conversely,

people who are chronically homeless really don’t belong in the current

emergency shelter system at all. An emergency shelter does provide them

with the basic roof and beds, Culhane acknowledges, but “their situation

is no longer an emergency. They’re stable. They’ve been there for

several years and they’re not leaving on their own.” Many chronically

homeless people require long-term supports — such as

caseworkers and mental-health providers — to help them manage their

daily lives and assist their movement to rental housing, boarding homes,

group homes, or hospices. Because of their high rates of

substance-abuse and mental illness, Culhane argues, many chronically

homeless people are best served with entitlement assistance, such as

Federal SSI (supplemental security income) payments. Finally, he says,

many episodic shelter-users would benefit most from residential

treatment programs (for substance abuse) or transitional housing as they

work toward reentry into the work force.

Culhane’s

findings for New York City mirror Philadelphia’s. “Legally, all we’re

required to do is to give them a bed and a roof and some food,” says

Susan Wiviott, “but the goal of the shelter system is to move out.”

Partly as a response to Culhane’s findings, Wiviott says, New York City

has turned its large shelters into smaller, more focused facilities with

specialized services, such as drug-treatment, mental-health, and

employment programs. “We don’t have to provide intensive services for

everybody,” says Wiviott, but for people who require special attention,

“we need to get to them quickly, because otherwise, they’re going to dig

in somewhere and they’re not going to move.”

For

Philadelphia, Culhane advocates a community-based approach that

capitalizes on the programs already in place in neighborhoods, targeting

new resources to fill in the gaps. Philadelphia’s Community Based

Homelessness Prevention Pilot Program was spurred by some of Culhane’s

earlier research, says City Councilwoman Happy Fernandez, who calls

Culhane’s work “spectacular.” That program, a collaboration between the

Energy Coordinating Agency and the Philadelphia Committee to End

Homelessness, takes a holistic approach to homelessness-prevention,

providing such resources as family counseling, housing counseling, and

energy assistance in two neighborhood centers, with the aim of

stabilizing families in the homes they already have and helping them to

remain stable through continued use of community resources. The two

centers, Dixon House in South Philadelphia and South Lehigh Action

Council in North Philadelphia, likely will be joined by a third site —

whose location will be influenced by the results of Culhane’s “Where the

Homeless Come From” study, which charts the prior addresses of families

admitted to the city shelter system.

Fernandez

leads the city’s Homelessness Prevention and Housing Stabilization Task

Force, joined by Culhane and a host of other homeless advocates and

city leaders. The task group met several times last summer to develop an

agenda for homelessness-prevention, Fernandez says; Culhane’s work was

“key” to the process, since no one else has given the city the

quantifiable numbers or the methodical insight into homelessness.

Culhane, she says, “has the hard data to guide and inform our planning.”

That

“hard data” may not be enough to convince some Philadelphia politicians

to support community-based planning, however. While everyone in City

Council agrees that city homelessness needs addressing, approaches

differ wildly. City Councilman James Kenney, for example, introduced

bills in October that would punish “aggressive” panhandlers and forbid

people from sleeping on sidewalks in Center City from 6 a.m. to

midnight. And last summer the city placed a cap on the number of shelter

beds it would provide, both to homeless families and to single adults,

reportedly in response to a $2.2 million reduction in state funds for

Philadelphia’s shelter program. According to Philadelphia Mayor Edward

G. Rendell, C’65, the city needed to save money for winter.

Approaches

differ among homeless advocates, too — and so do responses to

Culhane’s work. Dr. James Baumohl, associate professor of social work

and social research at Bryn Mawr College and author of the book Homelessness in America,

sits on the task force with Fernandez and Culhane; he thinks

community-based prevention efforts are too idealistic and expensive, and

he favors an approach that focuses on creating jobs and “sustained

income streams.” While Culhane has “demonstrated very nicely how common

the experience of homelessness is among poor people, particularly

African-American poor people,” Baumohl questions the validity of

Culhane’s findings; that is, it’s not clear to him what, exactly, the

findings mean.

Since

Culhane’s findings grew from data culled by intake workers at city

shelters in New York and Philadelphia, they are contaminated by the

limitations of such collection methods, says Baumohl; there is no

standardization. For example, he says, “there’s no way to know what

‘last address’ means, really.” Did the family report the address of the

last home they owned or rented? Or did they report the address of the

friends with whom they stayed for three weeks?

While

Baumohl criticizes Culhane’s data as consisting of “artifacts of a

screening process that is quick and dirty,” he doesn’t entirely discount

the worth of Culhane’s work. The findings are good for understanding

the dynamics of local shelter use, he acknowledges, “and that’s

fundamental for being able to plan something better.” Culhane’s work

clarifies trends, he adds, and absolute accuracy is less important than

the trend itself. For example, it is clear that the homeless population

will always be comprised of people with mental-illness and

substance-abuse problems — and that people without these issues cycle

out of homelessness more quickly.

On the whole, Baumohl concludes, Culhane “is doing an admirable job working in the trenches” — and his work is unquestionably “driving the process” in Philadelphia’s efforts to prevent homelessness.

RIDGE AVENUE ENTERS PHILADELPHIA at Roxborough, passing by modest homes and baseball diamonds, then crosses through Manayunk, paralleling the Wissahickon Creek and Fairmount Park. By the time it hits North Philadelphia, just before Broad Street, its surroundings have changed drastically. Boarded-up houses break up blocks where families still seek the outdoor comfort of the stoop on hot summer nights; on some blocks, the boarded-up places outnumber the homes. Signs still advertise meats and beauty supplies that haven’t been sold there for decades. Storefront after storefront wears graffiti-covered wooden boards in place of window panes, and bars or grates cover the shops that remain. In the afternoon light, people abound: some working, some shopping or waiting with small children for the bus, others passing the time, watching the neighborhood move and change. Nearly everyone is black.

Culhane’s “Where the Homeless Come From” study identifies this area as one of the three in Philadelphia from which a homeless family is most likely to emerge. Some 38 percent of families homeless in Philadelphia between the years 1990 and 1994 came from North Philadelphia, most of them from this area west of Broad Street. Nearly 70 percent of Philadelphia shelter families come from three areas: North Philadelphia, west of Broad Street and north of Fairmount Avenue; West Philadelphia, particularly Parkside/Mantua and Southwest Philadelphia; and South Philadelphia, west of Broad Street and south of South Street. One of the most significant predictors of the rate of shelter admissions in Philadelphia is a neighborhood’s proportion of boarded-up buildings, a condition also important in New York, Culhane’s research shows. Such areas tend to have very low property values and low rents, Culhane’s study concludes: “The combination of declining rental demand, low income generated by these properties, and the low resale value, predispose such areas to a higher risk of abandonment in the future.” Racial isolation also dominates these areas; indeed, the higher the rate of black people in an area, the greater the increase in shelter admissions over time. These areas also tend to have large proportions of female-headed households with children under age six — though as the children grow up and enter school, the families’ risk for homelessness declines, since their mothers are better able to work. Finally, families in these areas are more likely to “double up” in a house, despite the number of vacant buildings and the low rents.

“Really, what this is about is the very issues that community groups tend to focus on [for preventing homelessness]: housing, services, safety, and the adequacy of community supports,” says Culhane. Yet many community groups shrink from getting involved for fear that they’ll be asked to support the opening of a shelter in their own neighborhoods. What they don’t realize, says Culhane, is that advocacy goes a lot further than a new shelter: “I think what has to happen is that community groups and other political stakeholders in these neighborhoods have to understand that to take on the homelessness issue doesn’t just mean building a shelter in their neighborhood. It really means trying to address those underlying issues that they advocate for already.”

One example of the multi-pronged approach that Culhane advocates is that of Project HOME, which has established a residential recovery program for adult men addicted to drugs and alcohol; put together a package of after-school and GED programs, art-enrichment and aerobics classes; and worked with area residents (several of whom have joined the staff) to identify vacant homes for rehabilitation and vacant properties for turning into community gardens. Under the Philadelphia Plan, which pairs nonprofit agencies with corporations to revitalize distressed communities (the corporations get tax credits for their involvement), the agency has received funding from Crown Cork & Seal to rehabilitate houses.

“What I really think is going to prevent homelessness is strengthening communities, which is a multiple effort,” says Sister Mary Scullion, a member of the Sisters of Mercy and director of Project HOME. “It will take substantial commitment on the part of both the public and the private sector.”

In the wake of the recent Federal welfare reform, homeless advocates fear a surge in the ranks of the destitute. Philadelphia City Council members and others in city government have also repeatedly expressed concern for the future of city residents who have relied on AFDC (Aid to Families with Dependent Children) payments and Medical Assistance grants to get by.

“The fact that there are so many people who have some emergency need is indicative of the gaps in the safety net, in the safety system,” Culhane says. “I think some of the underlying principles that motivated the development of a welfare system — public assistance and subsidized housing, et cetera — some of the whole motivation for that was to prevent destitution … and homelessness, I would say, is fairly close to that.”

David L. Cohen, L’81, chief of staff for Mayor Rendell, described his fears for welfare reform in a November letter to The Philadelphia Inquirer. Some 50,000 Philadelphians will need to find employment in fiscal 1997 as a result of state and Federal welfare cuts, he wrote. “In addition, we estimate that 62,000 single adults between the ages of 19 and 59 will lose their medical assistance unless they work a minimum of 100 hours a month. Where will all these jobs come from? Over the last 25 years, the city has lost 250,000 jobs — an average annual loss of 1.5 percent of its jobs base.”

Dr. Michael Reisch, professor in the School of Social Work at Penn, says that the recent Federal welfare reform is “certainly going to increase the number of people who are homeless.” Many people receiving public assistance already lead “marginal existences,” he says; doubling up with other families in inadequate housing and taking other shortcuts to survive will “create an enormous amount of family tension and stress.” The new system, he adds, will mean a loss of income for many “marginal” families, exacerbating tensions as people fail to pull their own weight economically. As the conditions leading to homelessness become more frequent, he says bluntly, “You will have more people who won’t have a place to live.”

Concentrating solely on the emergency shelter system won’t bring an end to homelessness, Culhane insists. “We’ve really focused on this homeless population in trying to ‘fix’ them and fix the emergency shelter system: ‘Let’s make the shelters better and improve the services,'” he says. “I think all of that energy really misses the fact that there are much bigger forces at play.”

MEG EGAN, a former assistant editor for the Gazette, recently earned her master’s degree in social work at Temple University, and is working for the Women’s Law Project in Philadelphia.

SIDEBAR

URBAN NOMADS: A Poor People’s Movement

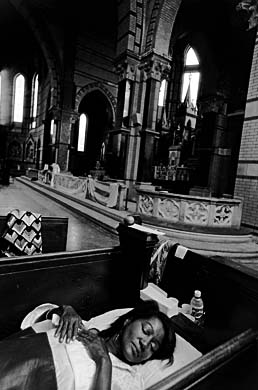

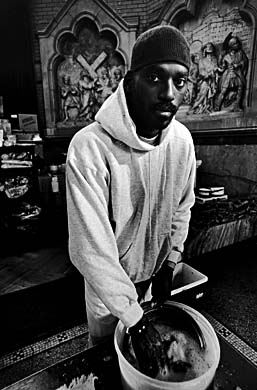

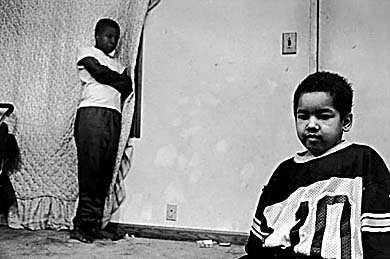

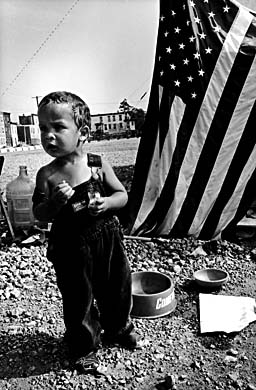

Harvey Finkle, SW’61, says that his driving passion as a photographer has “always been social-justice issues,” and those issues have led him to photograph refugees from Central America, Holocaust survivors, Indochinese immigrants — and, for the last 12 years, Philadelphia’s homeless. The images here are culled from “Urban Nomads: A Poor People’s Movement,” an exhibition in Houston Hall that runs through February. “This is a group of people who are mostly families–women and children and sometimes men–sometimes single men,” Finkle explains. “It’s a population that’s really mixed and multicultural — white, black, Latino — and it was really begun by a poor-people’s movement which began in Kensington: the Kensington Welfare Rights Union. It depicts a variety of things they’re involved in, including living on a lot, Tent City, and taking residence in an abandoned Catholic church.”

SLIDESHOW

Photography by Harvey Finkle SW’61