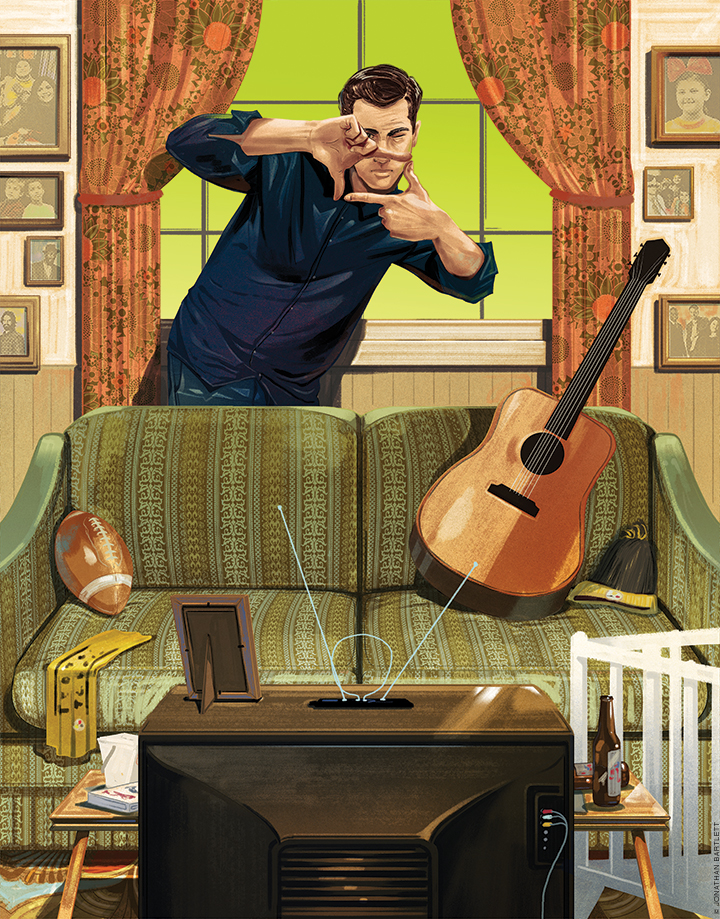

Long before he created last season’s top-rated new TV show, Dan Fogelman got his start listening to his Penn housemates’ stories and making them laugh with his.

BY ALYSON KRUEGER | Illustration by Jonathan Bartlett

On the evening of March 7, 2017, Hollywood writer and producer Dan Fogelman C’97 had a question for his 24,500 Twitter followers: “Everyone okay?”

It was one week before the season finale of his television show This Is Us was scheduled to air on NBC. There were many plot lines still unresolved on the breakout-hit show—the rare broadcast network program to capture the zeitgeist in the current era of prestige cable and streaming sites—and the show’s loyal viewers were an emotional mess.

“Um … no … not even close,” responded @sassycrazygal. “Gonna have to watch next week in a corner somewhere.”

“MY HEART IS ON FIRE!” posted @iAMgaither. “Why must you do this to me?!?!?!?!!”

This Is Us struck a special chord with audiences—Variety reported in May that it was the number one new show and fifth most popular program overall for the 2016-17 season, according to Nielsen ratings. But from the start of his career, Fogelman’s film and TV work has always tried to reach viewers by giving them everyday stories to which they can relate, then turning things up a notch (or more) from real life so they can’t look away.

His entrée to writing for films was an early screenplay mining the real-life emotional upheaval of a New Jersey teenager—with more than a passing resemblance to the author—going through his Bar Mitzvah. One of his most successful movies—Crazy, Stupid, Love, from 2011—is rooted in the misadventures of a long-married couple (played by Julianne Moore and Steve Carell) trying to rekindle a romantic spark in their relationship. Another,2012’s The Guilt Trip, starring Barbara Streisand and Seth Rogen, involves a mother and son bickering and bonding their way through a cross-country road trip.

This Is Us tells the story of the Pearson family—biological twins Kate and Kevin; adopted son Randall, born on the same day; and parents Jack and Rebecca. Some of the story is set in the present, as the siblings are turning 36 years old, but there are also extended flashbacks to their childhoods and to Jack and Rebecca’s early relationship and the day of the kids’ birth—when, in the big emotional moment that sets the series action in motion, Jack and Rebecca decide to adopt Randall, an African American infant abandoned at a nearby fire station, after the third of their expected triplets dies at birth.

The adult siblings all have their difficulties: Kate (Chrissy Metz) hates herself for being overweight. Kevin (Justin Hartley) stars in a hit TV-show—whose punning title, The Manny, tells all you need to know about it—but can’t focus on his serious acting ambitions or a relationship. In addition to struggling generally with his position in the family because of his race and adopted status, over the course of the season, Randall (Sterling K. Brown)—a successful trader in “weather commodities”—has to come to terms with finally meeting his biological father, who is dying. Meanwhile, in the past segments Rebecca (Mandy Moore) is torn between motherhood and pursuing a singing career and Jack (Milo Ventimiglia) struggles with an inherited drinking problem. (He appears to have died before the story’s present, in which Rebecca is married to his best friend, Miguel, played by Jon Huertas.)

Family stories have been a staple of TV from the beginning and have been set everywhere from the sitcom suburbs of Ozzie and Harriet and The Brady Bunch to the Cartwrights’ wild west, the Robinsons’ outer space, and the Depression-era mountain country of The Waltons. Modern Family—still going strong after eight seasons—is a more, well, modern example of the phenomenon.

“We had Parenthood, we had thirtysomething,” says Debra Birnbaum, executive editor for TV at Variety, naming two more standouts. “It’s not like [Fogelman] discovered this new genre or pot of gold that no one has thought about.”

But the extent to which This Is Us took hold across the country surprised nearly everyone.

The trailer for the show amassed 50 million views on Facebook—as compared to 15 million for Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens. Since premiering on September 20, 2016, This Is Us averaged 15 million viewers each week, close to the numbers reached by perennial audience favorite The Big Bang Theory, and trailing only that show and various iterations of primetime NFL broadcasts for viewers in the sought-after 18-49 age demographic to earn the fifth spot overall.

“That’s huge for a scripted drama,” says Robert Thompson, director of the Bleier Center for Television & Popular Culture at Syracuse University. “There are around 460 scripted shows currently active, and a lot of it is really, really good. Any program that breaks through that is a big deal.”

The response on social media was even bigger. On the day of the show’s finale, March 14, 2017, #thisisus was the number two trending topic on Twitter.

“When a show breaks out like this, where people are watching it when it airs and live tweeting it, that’s exceptionally rare in our age,” says Birnbaum. “People don’t want to miss this because they want to be part of the conversation.”

Count me in, too.

I am a triplet, and for my family, the show has been a form of therapy, giving us a glimpse into how another family with multiple births operates. My parents and two sisters all watched it every week, and then we would analyze it together over text or the phone. When we have family drama, we’ve started saying, “This is us.”

Since the show appears on NBC rather than, say, HBO or Netflix, this audience enthusiasm fueled media reports hailing it as a sign that broadcast television could still hold its own in the face of the rising popularity of cable and streaming services. A New York Times article carried the headline: “‘This Is Us’: Why TV Networks Are Hopeful.”

The program also ended the drought of industry recognition for network shows, which have been largely shut out from consideration at the big awards programs by cable and streaming entries. This Is Us won the People’s Choice Award for Favorite New TV Drama last January, and was the only broadcast network show nominated in its category, Best Television Series, Drama, at the 2017 Golden Globes (Netflix’s The Crown won). And in July the show was nominated as Best Drama Series—again as the only broadcast network entry—and Sterling K. Brown and Milo Ventimiglia were among the contenders for Best Actor at the Emmy Awards, scheduled to be broadcast on September 17.

Besides the love from regular viewers, celebrity fans and critics alike couldn’t stop themselves from publicly talking about how much the show affected them. Entertainment Weekly called This Is Us “a bear hug for a culture desperate for a little bit of that human touch.” The Atlantic headlined its analysis with, “This Show Will Make You Cry.” Singer-songwriter John Mayer tweeted while watching: “Not even wiping away tears for the next episodes. Just gonna let the first ones create tracks for a more even, efficient flow.” Comedian Sarah Silverman said it more simply with, “I’m a puddle of tears.”

Critics speculated on why the show was getting the reaction it did. Was Fogelman’s writing that good, or was it just fortunate timing that he created an emotionally cathartic show at a moment when Americans needed an outlet for their feelings? Another theory proposes that the acting is the key—the cast is so good, no one can turn away. Whatever the reason for the hold This Is Us had on audiences, the network took notice. In January, NBC announced it was renewing the show for two more seasons, which hardly ever happens in this era of fickle viewers and generally declining TV audiences. (Empire, the big new network hit of 2015-16, is still popular, holding the number six slot in 18-49 viewership, but saw a 33 percent drop in 2016-17.) Which leads to another question: Can This Is Us keep up and retain its devoted following?

Fogelman is certainly thankful for the show’s success—“I’m blessed,” he says repeatedly—but he’s not much interested in the speculation around why it’s become such a phenomenon. (Pitch, meanwhile, the other Fogelman-created TV show that debuted last season, about the first female pitcher in Major League Baseball, struggled to find its audience despite positive critical response and was cancelled after one season by the Fox Network.)

“I just write,” Fogelman says. “And I’m trying to get really, really good.”

Throughout the first season of This Is Us Fogelman checked on his viewers through Twitter. Randall’s learning about and coming to terms with his biological father was a major dramatic arc. During the episode in which the father died, he wrote: “I know. Everyone breathe.” After the show was over, he sent another message: “Are we on speaking terms yet, or do you need more time?”

While such comments might easily seem teasing or patronizing, Fogelman insists they were sincere and that he has always been overly concerned about those around him. “It isn’t because I’m some great person,” he clarifies, laughing.“It’s a degree of an illness that creates a hyperawareness of what is going on around me.”

As a kid he would go to movies and get so involved in worrying whether the person behind him could see that he couldn’t pay attention to what was happening on the screen. He remembers thinking something was wrong with him.

At Penn he would spend hours at night talking to his roommates about their lives and what was going on with them, remembers Siddhartha Khosla C’98, a musician and composer, whose credits include writing the music for This Is Us andE’s The Royals. “At least once a week we would hang out in our kitchen at two or three o’clock in the morning, very inebriated. We would talk about what we wanted to accomplish in our lives and what we wanted to do and who we wanted to be,” he says. “Dan would give us a pep talk. He pumped us up.”

Sophomore year Fogelman convinced 12 of these friends to move into a gigantic house at 4012 Spruce Street. “It was the most motley crew,” he remembers. “There was a star basketball player and two football players, an Indian guy from New Jersey, and a black guy from Los Angeles.”

The house threw such large parties, they got away with charging an entry fee. After one party, no one could find the pot of money, and a fight broke out. Everyone went to bed and Fogelman—wanting to make people laugh and feel happy again after the fight—stayed up all night writing a newsletter with funny articles about all the people in the house and posted it on their doors in the morning.

“Everyone read it—and lost it, because it was so funny,” says Khosla. “He started doing it all the time, and [that’s] when Dan became a comedy writer.”

Fogelman agrees: “It was the closest direct education I got, writing things and making people laugh.” (He also studied English literature and spent his junior year abroad studying the Victorian novel at Oxford.)

Senior year he got some maps from AAA and drove out to California to “take my crack at the industry,” he says. It was such a spontaneous decision he hadn’t even lined up a place to stay. Halfway through the road trip, he realized he would be homeless in LA and asked a friend’s girlfriend if he could crash with her. Soon he secured an assistant gig on the Howie Mandel Show and went from there to stints as a production assistant on The Man Show, the 1999-2004 beer-and-boobs Comedy Central program that Jimmy Kimmel co-hosted, and writing blurbs for the TV Guide Network.

He also grew his local network, making friends with fellow 20-somethings trying to make it. “We’ve always said we were like Entourage without the movie star,” he says. “We were all the hangers-on.”

By the early 2000s, Fogelman had advanced far enough in the industry that a series he created—Like Family, about black and white families sharing the same house—made it to air. It ran for a season on the WB network in 2003-2004. But his real turning point as a writer came when he gave a script he had been working on in his free time to another Penn friend, Jess Rosenthal C’97, then an underling at a management company, who now runs Fogelman’s production company.

It was a true-ish story, titled Becoming a Man, about what he went through leading up to his Bar Mitzvah. It even included a scene based on his father—Marty Fogelman, who helped start Babies “R” Us—getting into a fistfight with relatives at a golf game the day before the ceremony.

“I remember going to his house in Santa Monica and there being hundreds of pages of this script,” says Khosla. “That was the same Dan. Nothing has changed. He has his head down, and he’s working, and that is how it is.”

The film was never made, but the script was good enough to secure Fogelman a gig writing for a computer-animated film about a good-hearted but egocentric racing car and his companions, which turned out to be the 2006 hit Cars. It was a watershed moment. “You go back to LA, and you are the kid who wrote the next Pixar movie, and suddenly the world is at your fingertips.”

Foglelman’s current goal is to get into darker spaces with his writing. “I’m challenging myself to explore stuff that is less pleasant,” he says. “The last episode of This Is Us [was] a lot darker than anything we’ve done.”

The episode alternates between telling the fateful story of how Rebecca and Jack first met—she is singing at a bar’s open mic night, while he is contemplating stealing money from the same bar to open an auto body shop—and a gigantic fight between the couple that leads Jack to move out of the house and for the two to possibly divorce. The fact that the episode ended without revealing how Jack died or what exactly happened to their relationship or even if they had made amends before he died divided critics and left some viewers emotional but unsatisfied: “This Is Us season finale pulls off the show’s cruelest twist yet,” the headline from Diane Gordon’s review for Mashable, sums up this reaction nicely.

Until now, Fogelman’s creative ventures have been light and comedic. Cars is about an adorable vehicle who gets lost on the way to a racing championship and learns valuable lessons about how friendships are more important than trophies. Scripts for family-friendly Fred Claus—a saving-Christmas story leavened with a dash of sibling rivalry (Mom always liked Santa best)—and Tangled—a clever, girl-power reworking of the Rapunzel fairy tale for Disney—came next.

In 2009 he hammered out a story about a group of family members and friends whose crushes and love stories overlap. It caught the attention of Steve Carell, who helped convince Warner Brothers to buy it for $2.5 million. Crazy, Stupid, Love gained praise from critics who liked its unexpected turns and pleasant conclusions.

“What makes it worth watching, and worth liking, is the sense that it arrives at its warm and comforting view of things not by default but by choice,” wrote New York Times film critic A. O. Scott. (It also had a real-life happy ending for Fogelman. In 2015, he married one of the actresses in the film, Caitlin Thompson.)

Next came The Guilt Trip in 2012, which pairs Barbra Streisand and Seth Rogen as mother-and-son road-trip companions. The writer drove from New Jersey to Las Vegas with his beloved mother, Joyce Fogelman, to research the film. Many of the scenes in the movie—including one in which Streisand scarfs down a Texas-sized steak at a stop in the Lone Star State—are based on events that really happened. Fogelman’s recent film credits also include Last Vegas, in which a group of old friends—played by Michael Douglas, Robert De Niro, Morgan Freeman, and Kevin Kline—go away for a bachelor party, and Danny Collins, which he directed as well as wrote, about an aging rock-star (Al Pacino) who finds it hard to change his life.

While those films moved toward the more complicated emotional mix of This Is Us, Fogelman’s previous TV work was more broadly comic and offbeat, including the Princess Bride-ish musical-fairy-tale, Galavant, and The Neighbors (about a New Jersey family that moves into a gated community otherwise populated by aliens), which each had two-season runs on ABC.

In the summer of 2015, 20th Century Fox lured Fogelman from ABC Studios to its writing stable with an eight-figure deal. When they asked him what he was working on, he showed them a script he had been sitting on about three siblings with the same birthday.

Khosla immediately sensed its power.

“Dan has always understood who people are and where we come from,” he says. “He understands we aren’t just who we are today but the sum of so many different things, and there is a story behind every person that explains who we are and why we behave the way we do. This was a perfect example of that.”

This Is Us emerged in a challenging environment for broadcast television. Because the major networks still face regulations about what they can show in the way of sex, violence, and strong language, viewers have been migrating to grittier, more provocative shows on cable channels like HBO, AMC, and Showtime, or streaming services like Amazon and Netflix.

“The fact that there have not been many edge, zeitgeist-y shows on broadcast networks has not encouraged others to go there,” says Feinberg. “We’ve seen a mass exodus to cable and streaming.”

He points out that the last time a broadcast television network series was nominated for an Emmy was 2010, with CBS’s The Good Wife; no broadcast network show has won an Emmy since 2006, when Fox’s 24 took home the prize. So when This Is Us took off, the entire broadcast television industry cheered—and then immediately commenced trying to figure out why it worked, so they could imitate it.

“It’s the idea that if you can build it they will come,” says Birnbaum. “If lightning strikes once, it can strike twice.”

Some observers inside and outside of the show have said it was the right program for the Trump era. In an interview, Moore told The New York Times, “The uncertainty is in the air, and nobody knows what to expect in the next couple months, coming weeks, and year ahead.” For that reason people were looking for “cathartic entertainment.”

“I think it’s a little bit about the right place and the right time,” says Birnbaum. “When things are very complicated in the country right now, when things are dark, it’s about finding a show you can watch an hour of and have a good, cathartic cry. That is something people are really responding to.”

Syracuse University’s Thompson disagrees: “People are always temped to say because Z is happening in the world, Y television show is successful, but you can usually make the opposite arguments as well. During a Depression people might relate to shows about serious issues and hardships, but they also might want to live in a fantasy world of wealth and conspicuous consumption.”

He believes This Is Us is benefitting from the fact that so many shows have become about technology, science fiction, or the kind of fantasy realms depicted in a show like Game of Thrones. This Is Us is one of the only shows out there that is sincere, warm, and earnest.

“We are attracted to This is Us because it is a really good show of the type there isn’t a lot of,” Thompson adds, “so when we had a desire for that type of programming, that is the go-to.”

Pressed to speculate on his success, Fogelman laughs and puts out an argument: “It might all be bullshit, and I have these great actors who crush it every week.” Metz, Brown, and Moore were all nominated for best actor at numerous awards shows from the Golden Globes to the Screen Actors Guild.

“I will say this is an exceptional cast,” Birnbaum concurs. “There is camaraderie, there is professionalism, there is a support system. This is a cast that has been in the business for a long time, and they appreciate the success. They know it doesn’t happen all the time.”

The cast has put out behind-the-scenes videos of them celebrating the show’s renewal or playing pranks on fans. (They once knocked on a man’s door when they saw through the window he was watching This Is Us.) All have gone viral. The trailer for the second season, posted in May, is an exercise in meta-marketing in which the actors interrupt fans who are in the process of being filmed for a commercial about how much the show has meant to them. One fan reveals to Chrissy Metz that she named her daughter “after you”—meaning her character, Kate.

But neither fortunate timing nor top-flight acting would be sufficient if the show itself wasn’t first-class, says Thompson. “The number one factor to a show’s success is whether the show is good, whether it has characters we are interested in, whether it has stories we find compelling.” And all of that comes down to the writing.

Only time will tell if the show can sustain its popularity. “ This Is Us has already made history because it did a really fine first season,” says Feinberg. “Whether or not it goes down in history as one of the great television shows of all time will require a few more of those.”

That first season introduced the main characters and slowly showed how they relate to one another and became the people they are. There are still looming questions—how did Jack die? Why does Rebecca marry his best friend? Maintaining the intrigue after those situations are resolved will be hard, acknowledges Birnbaum.

“There is a lot of pressure on Dan,” she says. “But he has a good head on his shoulders, he has a plan for the second season, and it’s already planned out. I’m not concerned about it, but he does have a lot of work to do.”

Fogelman will also have to nail down the next two seasons while working on other projects. He’s currently in post-production on Life Itself, a multi-generational love story he wrote and directed that is set in New York and the Spanish countryside and stars Olivia Wilde, Oscar Isaac, Annette Bening, and Samuel L. Jackson. (In June a story on Entertainment Tonight’s websitequoted Fogelman on the “bizarre” experience, while filming in New York, of having people “run past the movie stars to come ask me how Jack died.”)

There are some other promising signs for the show’s staying power—starting with the fact that it managed to grab and hold an audience in one of the toughest seasons for entertainment television in memory, when the real world was providing plenty of drama all on its own.

“What made This Is Us’s success more impressive is that it happened in the face of one of the most widely covered presidential elections in the TV age,” says Feinberg. “It happened in the face of a World Series that everyone cared about because it went to seven games and involved the Chicago Cubs. It happened at a time when it didn’t have a regular schedule because there were some weeks it was off.”

It also has a story line that a wide range of viewers can relate to, upping the odds on their staying engaged.

“The funny thing about the show is everybody thinks it’s about them,” says Birnbaum. “For me, it’s about my father passing away. For other people, it’s about the weight issues. For somebody else it’s about being adopted into a transracial family. I think for everyone else it just taps into something.”

As a triplet, it’s been a powerful show for me. The other day when I was talking to a mentor about a particularly difficult childhood memory, I found myself referencing the show.

“Remember in the fourth episode when the family was at the pool, and Randall went to hang out with the black kids, and Kate was getting made fun of by her friends for being fat, and Kevin almost drowned in the swimming pool?” I asked.

(For the uninitiated, Rebecca was off trying to find Randall, and Jack was comforting Kate, so nobody was paying attention to Kevin.)

“Of course,” she said. “I couldn’t stop crying.”

“Well, in that moment I definitely felt like Kevin,” I said.

“Yeah, we all do sometimes.”

Alyson Krueger C’06 is a New York-based freelance writer and frequent contributor to the Gazette.

Hello Dan Fogelman and the other writers of this wonderful show, THIS IS US!

I truly love this show BUT one thing I find very interesting and odd in fact is that you never hear about the triplet they lost, you don’t see anyone going to the cemetery or if there is an Urn of ashes? this was a full term triplet, did they name the child? maybe I don’t recall?

I live this reality of losing a child, its a lifelong journey, so why is this in some way not a part of the show?

I can tell you that on my sons birthday, anniversary of his death, & holidays too I feel the need to be in that place acknowledging my child and his existence and honestly its everyday:( it’s just that those days are the toughest to get through….just curious?

You seem to make a point to go back in time to relationships and other issues with the families BUT not this one….yes, it’s hard, I know :(

I would love to hear from you :) blessings to all~donna