Revisiting a book that marked the end of one life and the beginning of another.

By Emily Rosenbaum

I sit on the futon chair in Benjamin’s room, his little body solid against me. His hair is thick, sticking up in the back, black-brown with red highlights. All afternoon, the right side of his hair was bright red, as was most of his cheek, his forehead, and the dining room floor. Crayola paint. But now the floor is mopped, and Ben is clean, pajamaed, and focused, ready for a bedtime book.

Four years old is a time of promise; he’s still my baby, yet it is clear that tomorrow and the next day he will learn new things that will bring him that much closer to growing up. Somehow, I cannot convince my children to stay babies, and this middle one surprises me the most, maturing while my back is turned. I’m busy potty-training the little one or helping the older one with his homework, and when I turn around, Benjamin is three months older. Tonight, however, for these minutes, I am all his, and he is waiting for me to read.

Lately, we have ventured into chapter books, and I’m reading him E. B. White’s The Trumpet of the Swan. Ben is completely taken with the story of Louis, a trumpeter swan born without a voice. Last night, we read Chapter 9, in which Louis’s father risks his life and soils his honor stealing a trumpet for his mute son. Ben didn’t breathe for about three pages.

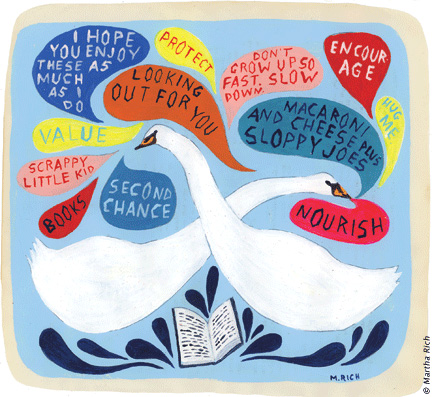

I have owned this copy of White’s classic for 27 years. The jacket has disintegrated; I use the few remaining shreds as a bookmark, unable to throw them away. I’ve known the cover picture—a little boy on a log, watching a cygnet tug at his shoelace—far too long to discard those slips of dust jacket. There is an inscription on the inside cover: “for dear Emily, I hope you enjoy these books as much as I did, because now they’re yours. Fondly Yours, Andrew.” Someday soon, one of my children will read that inscription, wonder who Andrew was.

Andrew Nowick was a cook at my overnight camp the summer before I turned 10. His sister was my favorite counselor, and his father was the camp director. That was the summer everything changed for me. It was the summer I was removed from my father’s house.

My stepmother had abused my sister and me for five years. She had starved us and beaten us and locked us out in the cold, while my father ignored the abuse. She told me I was worthless, taught me that I would never amount to anything. I was emaciated, dirty, empty, and focused entirely on surviving each day as it came. That spring, Social Services had investigated on the tipoff of some teachers. We denied everything. In the absence of our testimony, the social workers had to back off, but they brokered an arrangement in which my sister and I were shipped off to overnight camp for the whole summer.

At Camp Anderson, Andrew cooked the eggs and Sloppy Joes that filled my belly. I began to put on weight. His sister listened to my chatter, and his father facilitated Social Services’ renewed investigation of the abuse. They were nourishing my body and my heart as they worked to protect my future. Yet, Andrew understood that this was not enough. He knew that someone needed to show me that my mind was valued.

He gave me books. Stuart Little, Charlotte’s Web, and The Trumpet of the Swan. Somewhere along the way, Charlotte’s Web was lost. But, for the last 27 years, I have managed to hold on to the other two books. This is nothing short of a miracle, when you consider how many times I have moved. I have lived in 25 different homes across eight states, plus a stint in London. I moved those two books each and every time.

As a child, just entering adolescence, I read Andrew’s inscription and understood that there was an adult who valued me, even if it was only for a summer. Someone who wanted to share his favorite books with me.

There were others, many other adults who stood by me. My eighth-grade English teacher encouraged me to write, and my high school social studies teacher gave me second chances when everyone else thought I was falling apart. Because often I was falling apart, and what I needed was a second chance. At Penn, Professor Margreta deGrazia gave me a B because I wasn’t pushing myself, so I took another of her classes and worked harder, determined to earn the A from a teacher I respected. I built a life with the encouragement of mentors who believed in me.

Yet those E. B. White books remained special, long after Andrew and his family had faded from my life.

A few years ago, I found the Nowick family. The father had died, but I managed to get Andrew’s phone number. There is no hiding from former campers in the age of Google.

“I’m not sure if you remember me,” I began. Why should he remember a kid he knew for eight weeks almost three decades ago? But when I said my maiden name, he knew who I was. “You were this scrappy little kid,” he told me.

We chatted for a few minutes, telling each other about our lives, our children. We were both adults now. Yet Andrew was still the gentle soul I remembered, the man who had nourished my mind with books and my body with macaroni and cheese. The next day, we sent each other photos of our families.

Tonight, I read to my middle child from the book Andrew gave me. We finish Chapter 10, in which Louis vows to earn the money to pay for his stolen trumpet and restore his father’s honor. We move on to Chapter 11, “Camp Kookooskoos.” Louis, the voiceless trumpeter swan, has become a camp counselor. He has found a haven from his worldly troubles in the ephemeral seclusion of overnight camp. Eventually, of course, he will have to move on, mature, face the world of commerce and zoos, but for one summer, he is safe by the lake, playing taps for the children of Camp Kookooskoos.

I pull Benjamin a little closer by my side. I bend down to kiss his head, and the hair sticking up in the back tickles my nose.

Emily Rosenbaum C’95 GEd’96 is the author of Cooking on the Edge of Insanity, a collection of recipes and essays.