A crowd has gathered at the Moderne Gallery in Philadelphia’s Old City. They have come to view an impressive array of furniture by George Nakashima, and to mark the publication of Nature, Form and Spirit—a new book celebrating the late architect, designer, and craftsman, written by his daughter Mira, who sits in a corner inscribing copies.

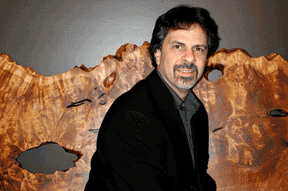

One man in black commands particular attention. He stays in one place; people gravitate to him. He speaks quickly and decisively, gesturing toward the spare, elegant pieces with authority—explaining, discoursing. He’s Dr. Robert Aibel C’72 ASC’76 Gr’84—sociologist, communications scholar, decorative-arts lecturer, filmmaker, author, furniture expert, and owner of the Moderne.

Aibel’s résumé mirrors the rambling course his career has followed since enrolling at Penn in 1968 to study sociology. A driven undergraduate, he completed the course work for his major in just three years—afterwards talking his way into the newly established Annenberg School for Communication, which was then closed to undergraduates. He submatriculated there as a senior (before submatriculation existed), with a particular interest in film. His program of study, no longer extant, was unique at the time.

“It had all different names,” Aibel recalls. “Visual anthropology, visual communication. But what we were doing was looking at how art communicates.”

While pursuing his master’s degree at Annenberg, Aibel worked as a teaching assistant and as a filmmaker. (He made the first film used by the admissions office to acquaint prospective students with Penn, he says.) Eventually, he enrolled in the Ph.D. program at Annenberg.

Fieldwork for his doctoral dissertation brought the newly married Aibel and his wife to Juniata County, Pennsylvania, for several months. Auctions were popular among the locals, so the couple began to attend them several times a week. Aibel the social scientist was intrigued.

“I instinctively saw them as a research opportunity, and analyzed the structure and function of the auctioneer’s patter as it served his social and economic roles,” he recalls. His observations gave birth to a scholarly paper and an award-winning documentary film entitled At The Country Auction.

At the same time, Aibel the entrepreneur saw a very different opportunity. “I began to buy [items] if they weren’t very expensive,” he remembers. “I also began to realize that if I learned more about the things that appealed to me and began to buy these items with resale in mind, there was money to be made.”

And so he became an antiques dealer, first specializing in American furniture and folk art, then moving on to more formal 18th-century pieces. In 1982, several years after starting his business, Aibel and his wife moved into a house with distinctive Art Deco features. Taking their cues from the architecture, they decided to fill it with appropriate objects and furniture—and to learn as much about the style as they could. Around that time, Aibel was awarded a grant to travel to France, the birthplace of Art Deco, in order to complete some research on the filmmaker Georges Rouquier. He worked quickly, freeing himself to devote as much time as possible to his developing interest. What he saw changed his life.

“It was a conversion of sorts,” he recalls. “The designs were incredibly innovative and broadly influential. I was so completely taken that I decided to change the direction of my antiques business—and, over the next few weeks, decided to jump in with both feet.”

Aibel spent his savings on a modest inventory of Art Deco pieces, brought them back to the United States, and advertised in The New York Times and elsewhere. Business was slow at first, but increased steadily. By 1984, he had rented a warehouse on 2nd Street in Old City. He had outgrown it by 1989, and moved to a larger space one block west, Moderne Gallery’s present location.

“I had no intention of [it] becoming my primary career, but I was working hard and things worked out in a way that I had never planned or expected,” he says.

As the gallery’s fame expanded, so did the focus of its inventory, which incorporated designs from across the 20th century. One subject of intense focus was Nakashima, whose work appeared on Aibel’s radar in the mid-1970s, though he didn’t become a noted Nakashima dealer and scholar until around 1989, a year before the designer’s death.

“I realized that unless people went to my warehouse around the corner, they didn’t realize I had any [Nakashima] to sell,” he says. “So I organized a small show in the gallery with little publicity, but it was very successful.” Another, larger exhibition followed in 1992; an even larger one in 1994 opened to rave reviews, as Nakashima’s importance to 20th-century design was beginning to be understood. Around that time Aibel struck up a friendship with Mira Nakashima. They have staged several other important exhibitions since, culminating in the current one, which runs through April 18 and coincided with the release of Nature, Form and Spirit, published by Harry N. Abrams.

Given the masterpieces of design and craftsmanship he works with every day, one might imagine Aibel tempted to hoard the best for himself.

“The worst thing I could do would be to have all the great stuff at home and have people wondering where it was,” he says. Given the myriad appraisals, sales, and consultations with museums, Aibel believes he has seen more than 8,000 pieces of Nakashima. “And in certain ways,” he admits, “that’s better than owning them.”

—David Perrelli C’01