A new exhibition at the ICA examines the early art, Arkestra, and Afro-futurism of the late Sun Ra.

By John Szwed

Related Link | ICA exhibit: “Pathways to Unknown Worlds: Sun Ra, El Saturn & Chicago’s Afro-Futurist Underground, 1954-68”

Some years ago a journalist headed his review of a Sun Ra performance “Genius or Charlatan?” He might well have added “madman” to his question, because these are the roles in which this musician and longtime resident of Philadelphia was cast. Now, with a new exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, we can add the role of Afro-futurist.

Sun Ra, born Herman Poole Blount in Birmingham, Alabama in 1914, went to great lengths to deny his earthly origins, and to claim his birthplace as Saturn. Part mystic, part shrewd showman, part teacher (he had a teaching degree from Alabama A&M), he distanced himself from earthly matters to stake his future (and that of the world) on a set of unique ethical and spiritual ideas he had synthesized from theosophy, Afro-Baptist doctrine, philology, numerology, and science fiction. His claims of identity shifted throughout his life from black man to spaceman to a member of the “angel race,” and his teaching changed with his personae.

There was that, and then there was Sun Ra the pianist, composer, and arranger who moved from the South to South Side Chicago in the 1940s to reach new people. He worked with some of the best in black music—blues singers Wynonie Harris and Lil Green, and the father of swing music, Fletcher Henderson. But he had his own musical ideas to develop, most of them related to his utopian vision of a future built on enlightened technology, which was drawn from the most advanced science and from ancient Egypt (the latter for its links between the spiritual and the scientific). No one who knew him denied his musical originality, though they often ignored its mystical underpinnings.

To break through the barriers of the music business, and to reach beyond the Chicago black neighborhood in which he had made his name, he began to record, package, distribute, and sell his own recordings, a business plan that was virtually impossible to realize until a few years ago. But, as Sun Ra said, “The possible has been tried and failed. Now it’s time to try the impossible.” By then he had joined a group of neighborhood mystics who met and planned for the future, and several of them became his partners in a recording company they called El Saturn (Sun Ra’s house, incidentally, was right next to the El train in Chicago).

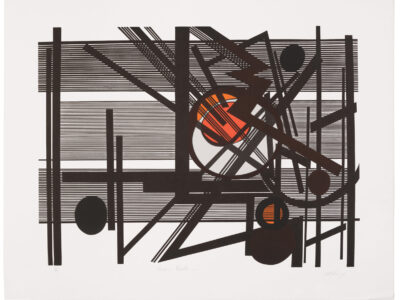

The record covers and disc labels of El Saturn were particularly striking: They were typically made from original paintings of futuristic architecture or dreamscapes, each of them exploding with color and shimmering with gold or silver. But the covers were more than paintings. Their backs often featured poems and even short lectures by Sun Ra, the whole package “disguised as jazz,” as he would say. Today they are much sought after by collectors.

It was easy to be puzzled by Sun Ra’s Afro-Platonic neo-hermeticism. He gave tireless jeremiads in the form of interviews in which he argued that it was time to reexamine the assumptions on which our daily lives rest, and that, unlike other philosophies and religions of earth, his message affirmed life, not death. But his sermons could be ignored by philistines.

Things changed radically after he moved the band (called the Arkestra) from Chicago to the Lower East Side of New York, and then, in 1968, to Philadelphia. There they took up residence in a house owned by Arkestra member Marshall Allen on Morton Street in Germantown—the same street on which Mayor Frank Rizzo had once lived. (It remained the home base of the Arkestra even after Sun Ra died—or returned to Saturn—in 1993.)

The band’s six-hour multimedia barrages were truly frightening experiences. The music moved from howls and shrieks to African drum bursts and the pastoral sounds of bird calls, all coming from an Arkestra dressed in space suits or maybe medieval jerkins, with dancers swirling across a smoke-filled stage and out into the audience (“butterflies of the night,” one French critic called them). Other performances offered gilded muscle men, contortionists, fire eaters, and little people parading about in front of shadow puppets, masks, and films of the pyramids (or North Philadelphia row houses). It out-Wagnered Wagner at Bayreuth, and it out-hippied the acid rockers, like Pink Floyd, who borrowed from him.

Music of the Spheres: Sun Ra, circa 1960 (above); Aye, a black-light painting, circa 1970 (left); album cover for Cosmic Tones for Mental Therapy (right).

The ICA exhibit—“Pathways to Unknown Worlds: Sun Ra, El Saturn & Chicago’s Afro-Futurist Underground, 1954-68” —stresses the futurist Sun Ra. It features samples of El Saturn’s original LP cover art and preliminary sketches for covers, Sun Ra’s unpublished book of verse, the band’s business cards, and building plans for a Cosmic Research Center. There are also some broadsheets of Sun Ra’s philosophical and linguistic musings that he distributed in Hyde Park in Chicago, where he often held forth as a speaker, competing for listeners against Baptist preachers, the Black Muslims, and various street corner Egyptologists.

The closest the exhibit comes to the music is with Edward English’s Space Ways and Phil Niblock’s The Magic Sun, two early experimental films. Some of the Arkestra’s costumes would have been welcome in this exhibit, and they would have underlined how much Sun Ra got from the Buck Rogers cartoon strips—the albums’ bright red and gold colors, the suits that suggest the Archers of Arboria and people from the planet Mongo.

When Sun Ra came to Philadelphia he assumed complete control over his recordings, leaving his Chicago partners behind, and one of the consequences was that the album covers grew simpler, plainer, more generic, and more of them were handmade. It was not the Quaker influence of Germantown that steered him in this direction; it was limited funds and lack of time. Musicians who rehearsed all day were not emotionally or artistically suited to elaborate artwork. When I heard the Arkestra at Swarthmore in the late sixties, I saw a table filled with white album covers with the barest of titles written on them with magic markers. And when I asked the Arkestra member who minded the table to tell me what kind of music was in those albums, he pointed to two, and said, “This one is outer space music and this one is cocktail music.” When I listened to them later, I saw that he was more or less correct. But by then, Sun Ra had broken down all earthly boundaries between musical genres, and neither type of music would ever sound the same to me again.

John Szwed is professor of music and jazz studies at Columbia University, and the author of Space Is the Place: The Lives and Times of Sun Ra.