Whether the cry from Quaker fans has been “Hurrah!” or “Help!” the Gazette has been there to record the wins, the losses, and the would/could/should have beens.

By David Porter

The peculiar institution of intercollegiate athletics has existed in one form or another at Penn since well before the start of the 20th century. It is a rich history that has reflected the seismic shifts in the role sports have played at the collegiate level and in America at large, and a journey through the pages of the last 100 years of the Gazette reveals, more than the ephemera of the triumphs and defeats on the field of play, the ongoing redefinition of what that role is and what it should be. From the century’s early decades, when control of athletics moved from the alumni to the University proper, to the decision to continue athletics during wartime, to the national successes of Penn’s football team and the subsequent sea change in philosophy under the Ivy Agreement, to the clash with the NCAA over student-athlete eligibility, many of the debates revolved around issues that confront college sports in 2002.

The Gazette did not shy away from reporting and commenting on the controversies and shifts in power that marked the sports century at Penn. Through changes in format, frequency, and tone, the magazine continued to serve several functions: as chronicler of athletic deeds, booster, critic, defender against attacks (real or imagined) from the mainstream press, force for change, and, not least important, as an outlet for generations of alumni to fulminate on such topics as the need for a University-sponsored course in Golf 101 or those ghastly uniforms that “made the marching band resemble the Salvation Army.”

In the early days stories carried no bylines, but by the mid-1920s a sports-publicity apparatus had been put in place by the University that produced regular articles for the Gazette. Game stories contained no quotes—Penn’s University Council on Athletics had barred players and coaches from granting interviews—and seldom was written a discouraging word unless to denounce accusations by rival schools or the daily tabloids.

The gloves came off in the 1960s as writers like Frank Dolson W’54, Alan Richman C’65, and Bob Savett C’70 WG’81 took unflinching looks at the University’s overall athletic program. Longer, more personal stories came in vogue in the 1970s, symbolized by Patricia McLaughlin’s account of skating with the fledgling women’s ice-hockey team and Savett’s “Anatomy of a Melting Pot,” which explored the racial, religious, and ethnic mix on the 1973-74 men’s basketball team.

Following are some of the high- and lowlights of the last 100 years of Penn athletics, as reported in the Gazette:

The Early Years

“In many of our universities at the present time, thoughtful and liberal men among the graduates and faculty are asking themselves the question: Are we not going too far, in our headstrong American way, in the matter of intercollegiate contests?”

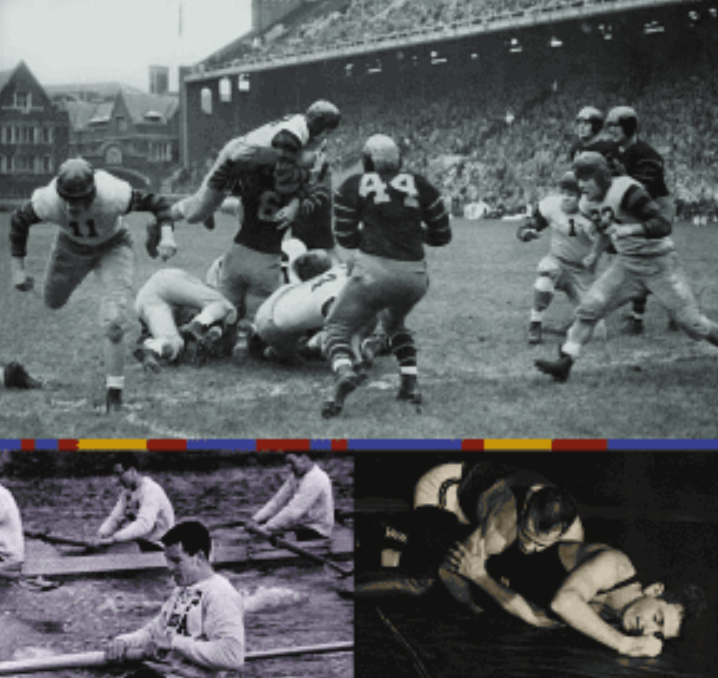

These words of Harry C. Thayer C1892 (a former Penn fullback, who nevertheless agreed that, yes, we were) appeared in the December 31, 1904, edition of Old Penn, the precursor to the Gazette. They struck a note that would ring throughout the 20th century in debates over intercollegiate athletics. His concern centered on football, which in the early years of the century was a savage, brutal game that routinely produced broken bones and, on occasion, fatalities. Though none of the latter occurred at Penn, the magazine’s 1903 game account of the Quakers’ 42-0 victory over Cornell in the annual Thanksgiving Day game concluded, “It was a fierce game, in which injuries were plentiful, the Cornell men having the worst of it.” A 1905 game description recounted how “the players on both teams lost control of their tempers, became overexcited, and the results were a series of penalties for slugging, holding and other unfairness.”

Old Penn supported the national rules changes and other reforms aimed at cleaning up football, and in an augury of sorts, the University took a leading role in pushing for change. As early as 1905, Penn’s Committee on Athletics mailed a memo to “1,500 educational institutions throughout the country,” according to the magazine, calling for rules that would ban recruiting and require all team members to be actual students and in good standing academically. In an era when mercenary players hopped from one school to another and were routinely paid for their services, the headlong collision between the ancient Greek ideals of education of mind and body and the baser elements of the new American sports culture was nearly audible. As the Gazette noted in 1912, “Our definitions of amateurism and professionalism, copied as they are from foreign sources, cannot be readily adapted to the American college student, and a fairer and more reasonable definition would eliminate a vast amount of hypocrisy.”

Athletic Department Perestroika

From the first days of organized athletics at Penn in 1873, sports were funded and overseen by the Athletic Association, an alumni group that made regular appeals to its members through the Gazette. As the move toward universities’ exerting greater control over their athletic departments gained momentum nationwide, however, in 1917 Penn placed athletic oversight in the hands of the newly-created University Council on Athletics, which was composed of faculty and students as well as alumni. The Athletic Association still held the title to Franklin Field, but the Council would “control and manage all athletic sports, contests and exhibitions and determine the eligibility of participants therein, receive and disburse all moneys arising therefrom” as well as employ all coaches.

The Gazette reported the developments faithfully, but cautioned on January 6, 1922, that “there are, however, a great many alumni who are still intensely disappointed because the creation of the University Council on Athletics … practically severed all connection between the administration of athletic sports and alumni membership in the Association … Some even go so far as to say that until it is revived Pennsylvania cannot expect to regain the honored position her athletic teams, especially in football, held at one time.”

The dire predictions failed to materialize, as the football team never dropped below .500 in the 1920s and had a three-year stretch in which it lost just four times in 29 games.

The Gates Plan

If the revamping of athletic control at the University in 1917 was a bold move, the reforms instituted in 1930 by new President Thomas S. Gates W’93 L’96 Hon’31 Gr’46 were the equivalent of Columbus setting sail for the New World. For years, University presidents had struggled with the over-emphasis of varsity athletics in general, and in particular the widening philosophical chasm between college football teams and the schools they represented. Yet few had had the wherewithal to take decisive action until Gates, a former partner in J.P. Morgan & Co., tackled the 500-pound gorilla head-on with sweeping changes that sent ripples through campuses across the country.

The Gates Plan, as it became known, took control of all athletic functions from the Council on Athletics and placed it in the hands of a new Department of Physical Education, which would be accountable to the University administration, just like the math, chemistry, and philosophy departments. It also decreed that any coaches who weren’t already members of the physical-education faculty become so, and assigned them to assist in the development of intramural sports. The second and third floors of the training house, once reserved exclusively for varsity athletes, would host the student-health headquarters. A playing field was developed between the University Museum and Franklin Field, and other playing areas were studied for use by intramural teams. Student ticketholders were even given preference for center-field seats at football games. “Sports for all” had replaced “sports for the few.”

The effects were felt immediately. Student participation in sports swelled; the Gazette remarked in the fall of 1931 that about 800 students had tried out for the varsity, junior-varsity, freshman, and scrub football teams, while fraternities and dormitories were organized into leagues for intramural competition.

“The responsible college world knows that [President Gates] is right and will watch the Pennsylvania plan hopefully, looking to the time when in every educational institution in this country his leadership will be acknowledged and his example will be followed,” The New York Times wrote. The Philadelphia Inquirerpredicted, “Eventually the rest must come into line. They will profit, of course, from Penn’s mistakes. Meanwhile they are paying heavily for mistakes they continue to make in their present pursuit of an aimless policy.”

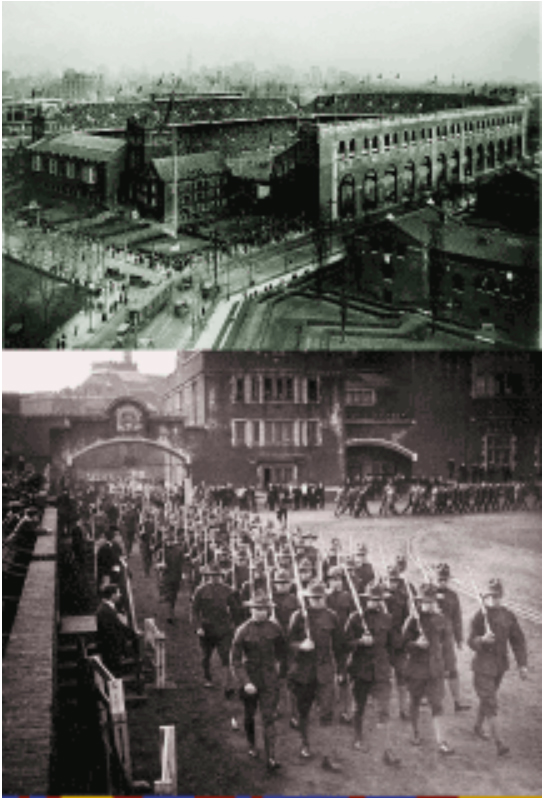

Franklin Field: From Standard-Bearer to White Elephant

Long before the term “multi-use” became synonymous with the cookie-cutter designs of sports stadia in the 1960s and 1970s, Franklin Field, the brick-and-steel behemoth at 33rd and Spruce Streets, could lay claim to the title. Erected as the first horseshoe-shaped stadium in the country in 1903—and finished by non-union carpenters and “student volunteers” after union carpenters went on strike—at various times it hosted football, track and field, baseball, lacrosse, soccer, field hockey, and intramural sports—not to mention an al fresco production of Verdi’s Aida, military exercises for the U.S. Navy, and a large-scale Christmas tree sale. Weightman Hall, which closed the open end of the horseshoe at the west end of the stadium, was dedicated in December 1904, and featured a swimming pool, gymnasium, and locker rooms. The training house was completed by the fall of 1907.

As college football flourished after World War I and more and more fans found themselves turned away at the gates, the Gazettebegan its pleas for a bigger stadium, writing that “the athletic authorities of the University cannot delay until another year to find some method for enlarging Franklin Field.” It continued the drumbeat until the University board of trustees approved plans for a new stadium in 1921, and work began the following May with the demolition of the old structure. The finished stadium, which cost about $725,000, hosted its first game on September 30, 1922, though only 29,000 seats were ready for use. A crowd of 48,000 attended the official dedication a month later at the Penn-Navy game.

A prescient Gazette article noted, “At the rate interest is now growing in intercollegiate sports, particularly football, it may be that even this large field will prove inadequate for the football and relay crowds.” It took less than three years for the trustees to approve a plan to put an upper deck on the field and increase its seating capacity to more than 70,000, making it one of the largest college stadiums in the United States. Even that was not enough, as it turned out: For a game against Illinois and the legendary “Red” Grange in 1925, “100,000 seats would have been none too many.”

The tune had changed by the late 1950s, after the Ivy Group Agreement brought an end to big-time football at Penn and the University resorted to luring the NFL’s Philadelphia Eagles in order to make up some of the revenue shortfall. “It is no secret that Franklin Field has long been regarded as a ‘white elephant’ and that it has been responsible for a large part of the annual athletic deficit,” Daily Pennsylvanian editor Kenneth W. Sehres W’58 noted in a column reprinted in the Gazette.

As football attendance dwindled steadily in the 1960s and 1970s, the Penn Relays, and track and field in general, became the biggest draw at Franklin Field. No structural renovations could improve the notoriously fickle Philadelphia weather, however. Legendary Quaker track coach Lawson Robertson is said to have muttered in 1931 while turning up his collar to ward off another spring squall, “These Relays started in 1895—and it’s been raining ever since.”

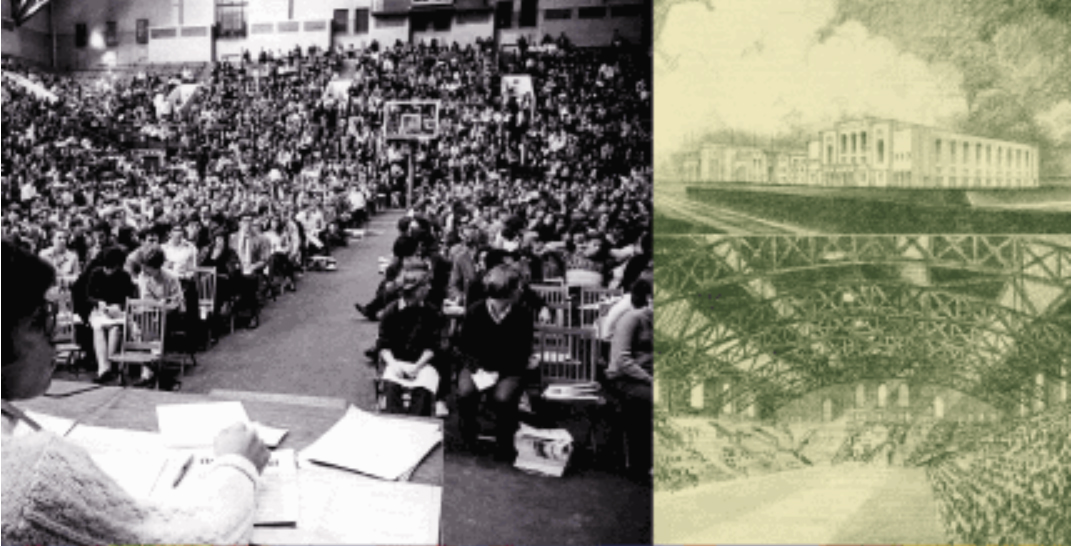

“The Barn”

With the basketball team beginning to outgrow the cozy confines of Weightman Hall by the early 1920s, the Gazette, as was its habit, sounded the call for a new athletic building “which can be used for indoor baseball practice, and which can also be converted into an auditorium large enough to accommodate the crowds which wish to see college basketball.” Plans were finalized five years later for an indoor arena, gymnasium, and swimming pool complex. The arena’s seating scheme, with spectators entering short ramps into the middle of a section so they would walk up or down to their seats, was termed “unique for this section of the country.”

Naming the new arena took a little maneuvering. The University Council on Athletics favored “The Colosseum,” while the board of trustees nominated “The Palestra,” a derivation of the ancient Greek “Palaistra” suggested by Dr. William Bates, professor of Greek. Bates had also considered “Ephebeum” or “Konistra” (the Greek equivalent of “arena”), neither of which exactly rolled off the tongue. In its report of the decision to name the building The Palestra, the Gazette wrote on December 17, 1926, “To those who wanted a name that would stick in the minds of the public, the committee believes that the new name will accomplish this.”

The cavernous arena, referred to by some as “The Barn,” opened for business on New Year’s Day, 1927, with a 26-15 Penn victory over Yale in front of nearly 10,000 people, “marking a record in basketball attendance for the Eastern part of the country,” according to the Gazette. In the 75 years since, excluding 1943 to 1946 when it served as a mess hall for Navy and Army personnel, the Palestra indeed has stuck in the minds of the public. The “ancient echo-chamber of horrors” for visiting teams moved writers to wax nostalgic as far back as the 1960s. Alan Richman called it “the University of Pennsylvania’s last link with the world of big-time amateur athletics” in a 1964 article that described the since-outlawed practice of rival schools’ fans unfurling derogatory banners during games. He also took jabs at Penn’s reserved fans, saying, “The trouble with the Pennsylvanians is that they lose interest in the game if the Quakers fall behind by more than five points,” and added, “They have the laziest cheerleaders in existence.”

Sports During The Wars

While other Eastern colleges suspended their athletic programs when the United States entered World War I, Penn took the lead by maintaining its teams during the conflict, and what developed was an early version of intramurals. Anyone who came out for football was able to play—there certainly were slots available, as the Gazette noted in December 1917, that “every regular and substitute” from the 1916 team was “either in actual war service or was rejected for physical defects.” The NCAA endorsed Penn’s decision, and other schools followed, spurring the New York Journal to call Penn “the guiding star of present-day athletics.” The Gazette remarked that “it is gratifying to know now that virtually the entire college world has accepted the stand originally taken by Pennsylvania.”

The drill was repeated during World War II, and in March 1942 the Gazette noted that more than 300 undergraduates were actively representing the University in the winter sports of basketball, wrestling, swimming, fencing, squash, and indoor track, while hundreds more participated in intramurals. “The success of our basketball team and the achievements of the football team during the war years are indicative of the wisdom in keeping athletics going during the times of stress and strain,” a March 1945 article noted, adding that “to have closed Franklin Field ‘for the duration’ would have been a calamity to the community.”

One of the Gazette’s most important functions during the war years was as a welcome source of news for alumni engaged in battle in remote corners of the world. “Your card has chased me halfway around Africa, Tripolitania, Tunis, and Italy, but it has finally caught up with me,” Major Alfred J. Wilde C’22 wrote in the October, 1944 edition. “My job has been intensely interesting throughout, but there are many of us who are hoping to settle down to a normal football season at home next year.”

Few sentiments were stated so poignantly as these from rower Richard M. Marshall C’39 to his former coach, Russell “Rusty” Callow, which were printed with Callow’s permission in the May 1942 edition of the Gazette:

There are so few people to whom I could even write like this. I like fighting mankind—men that can row the last mile at the 44-stroke, who can make a touchdown in the last minute of play to come from behind. Men like you, Rusty, and my father who get a kick out of their fellowmen and who can take life in stride … I do not know what the next months will bring me. I am engaged to be married in a few weeks. We both know what it means, what the odds are and know that we want what few days we can have together. Having those days, before going over, the enemy will find me in a snarling hurry to smash them down and come back.

This is one of those “last quarter-miles.” We’ll take them, Rusty, and I’d like you flying on my wing.

Please give my best to all you see that I might know. And the next time you have a meeting with the University board, tell them at least one alumnus greatly loves the Red and Blue and all it stands for …

Am taking a three-mile run every other day to keep the old waist-line down.

The Gazette reprinted the letter in its entirety in June 1943, a month after Major Marshall was killed in action.

The Ivy League: From Concept to Reality

By the late 1940s the idea of an “Ivy League” consisting of several of the oldest football-playing universities in the East had been kicked around for decades. Meanwhile, Penn’s football schedule continued to reflect its national profile (Notre Dame, California, Wisconsin, Penn State, Michigan) as well as its traditional Eastern rivalries (Cornell, Army, Navy, Princeton). A Gazette poll in the winter of 1948 found that alumni favored a schedule that included six Ivy schools (excluding Brown) plus Army, Navy, Penn State, and Michigan. This apparent schizophrenia was reinforced by University President Harold Stassen Hon’48 in an address reprinted in the Gazette in April 1950, in which he advocated re-establishing relations with Harvard and Yale while also scheduling some of the strongest teams in the country. This philosophy, combined with the radical changes brought on by the official formation of the Ivy League two years later, would eventually bring Penn’s once-proud football program to its knees. Between the signing of the Ivy Agreement in 1952 and the initiation of a full round-robin schedule in 1956, the Quakers—whose big-time football opponents had been scheduled

before the signing—went 3-5-1 in 1953 and lost 18 straight in 1954 and 1955 [“Harold Stassen and the Ivy League,” November/December 2001].

Many alumni were predictably outraged by the turn of events, though not all yearned for a return to the glory days. “It is up to each of us to stand solidly behind the coaches, the players and the student body as long as they represent the ideals of true Pennsylvania sportsmanship,” one reader wrote, in sharp contrast to another who suggested that the Gazette “poll [alumni] as to their ideas on the new high-school level of athletics being introduced at Penn.” Another fumed, “Let’s get out of the champagne-appetite-with-the-beer-pocket-book class or else play second grade colleges.”

1960s: Decade of Defeats

One of the soothing aspects of sports is that for the most part they exist in their own little vacuum, oblivious to, and unaffected by, the turmoil in the world outside the white lines. That changed during the 1960s, as the athletic department found itself beset with crises from within and without.

Penn President Gaylord P. Harnwell Hon’53 summed up the state of Penn athletics in a 1964 letter reprinted in the Gazette: “There are those, of whom I am frank to admit I am one, who believe that in recent years not all of our athletic achievements have kept pace with the rich traditions of the past. Our total efforts should produce our fair share of victories.” The slump to which Harnwell referred was genuine: from the fall of 1955 to the spring of 1964, Penn’s teams won 334 games and lost 512, an underwhelming winning percentage of 39 percent.

A committee recommended improving facilities, consolidating the athletic and physical-education departments under one director, and lifting the ban on spring football practice. “We should enter every contest with a team that is capable of playing on a par with its opponent and with a reasonable expectation of winning,” the Gazette quoted from the report in February 1965. “Only if we greatly improve our facilities, the participation of our students, and the morale of the whole University family can we hope to obtain this modest goal.”

The wins did not come fast enough to save the job of athletic director Jerry Ford, who was asked to resign in 1967, reportedly after confronting University officials about rumors of Penn’s football team conducting spring practice, and of a slush fund being used to pay for athletes’ tutoring, both in violation of Ivy League rules. Dr. Harry Fields, assistant to the president for athletic affairs, admitted some rules had been broken but termed the violations “innocuous.” To replace Ford, Penn went outside the Ivy League to hire former UConn assistant athletic director Fred Shabel. In contrast to Ford, who was seen as a zealous defender of Ivy rules and regulations, Shabel brought a more business-like attitude to the job, telling the Gazette in November 1967 that what was needed was “massive organization, massive selling, massive public relations, and massive heart.”

By decade’s end, the new approach had begun to pay off. Penn’s teams had a 64 percent winning percentage (72-41) in 1968-69, a figure that rose to 70 percent if the 1-11 men’s ice-hockey team, resurrected the year before and destined for extinction within 10 years, was discounted.

Penn vs. the NCAA

As Penn’s results on the field improved incrementally through the mid-’60s, the University and the rest of the Ivy League ran afoul of the NCAA in 1966 over, of all things, academic standards. The Ivy schools refused to cleave to the NCAA’s rule that all student-athletes must have a 1.6 grade-point average (out of 4.0) to be eligible to compete. As Penn’s Ford said at the time, “How could the Ivies accept legislation that assumed a distinction between ‘student-athletes’ and the rest of the student body?” In February 1966, the Gazette’s Frank Dolson pointed out, “Here was a law passed for the purpose of forcing low-standard schools to raise their academic level that might result in penalties being imposed upon a league noted for its high standards.”

The punishment came swiftly. Penn’s Ivy-champion men’s basketball team was banned from the NCAA Tournament, declared academically ineligible, “to compete with the High IQ boys from Syracuse in a tournament eventually captured by the Mental Giants of Texas Western,” as Dolson wrote sarcastically in April. Twelve years later, in a letter to the Gazette, Stan Pawlak C’66, a member of that team, wrote that “my disappointment has turned into a degree of bitterness” over the decision by Ford, “who simply wanted to make an unnecessary stand on the issue.”

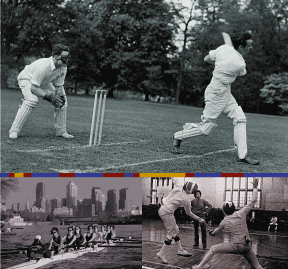

Title IX

Women’s sports at Penn dated back to the formation of the Women’s Athletic Association in 1921, though one would have been hard-pressed to divine that fact from reading the Gazette, which covered women’s sports sporadically, if at all. A roundup of women’s team results appeared in the magazine with slightly more regularity in the 1940s, but coverage was still restricted to an occasional photo accompanied by a minimal amount of text.

With the passage of Title IX in 1972, the issue of women’s sports moved into the spotlight. “In the past few years women have struggled to raise their level of consciousness, a goal heartily applauded by men, since it cost nothing,” Alan Richman wrote in March 1975. “Now women athletes want to raise their budgets so they can have the same opportunities as male athletes. This idea is considered far more radical and dangerous by the collective forces of male superiority.” Richman surveyed the Ivy League’s athletic directors and found them unafraid of the new regulations, even though at the time most of them presided over budgets that were tipped heavily toward men’s teams.

“The Ivies as a group are much more advanced in their thinking regarding the development of women’s athletic programs,” Penn athletic director Fred Shabel told Richman. “A key factor here that makes things a lot easier is that, unlike grant-in-aid schools, all students are eligible for financial aid, whether he or she is a clarinetist, a quarterback, or a tennis player.”

Before long, volleyball, gymnastics, fencing, crew, and ice hockey had been added as women’s sports, and Patricia McLaughlin’s 1975 feature story on the Penn field-hockey team noted that The Daily Pennsylvanian had actually begun assigning a reporter to cover that team.

1970s: Decade of Deficits

If mounting defeats preoccupied Penn alumni in the early and mid-1960s, the athletic department’s increasing deficits became a sore spot in the late 1960s and well into the 1970s. “When I receive pleas to increase my Annual Giving, and note that Penn must have had a sports deficit of about what it collects in Annual Giving … I again am filled with doubts as to the wisdom of Penn’s present course,” Arthur E. Conn W’28 wrote in the March 1968 Gazette. “I wonder whether my few dollars and those others give are used for academic purposes or to pay the expenses of maintaining an athletic posture that becomes more revolting to me each year.”

In a lengthy article in October 1970, Bob Savett revealed that the University’s athletic expenditures increased 19 percent from 1955-56 to 1964-65, but 73 percent from 1964-65 to 1968-69, the year Penn teams achieved their highest combined winning percentage of the decade. The money had indeed bought victories, not to mention Gimbel Gym, a synthetic track and Astroturf at Franklin Field, new locker rooms at the Hollenback Center, the Class of ’23 Ice Rink, and an addition to the Ringe Squash Court. Gate receipts had remained the same during those four years, however, and by the spring of 1971, student and faculty complaints about the athletic department’s $1.3 million deficit led President Martin Meyerson Hon’70 to appoint a committee headed by English professor (and former basketball star) John Wideman C’63 Hon’86 to seek solutions. “The faculty has lost control of athletics,” Wideman told the Gazette. “The faculty has minimal input into the Ivy Group or into our internal situation. So, in a financial emergency, there is a complete lack of understanding.”

The debate over the direction of Penn athletics, and the Ivy League in general, continued throughout the 1970s as attendance at sporting events continued to drop. In April 1971, Dolson criticized Penn’s “lust to be number one … [that] was so strong that it overrode everything else, including the principle that the University and league are supposed to stand for.” The possibility of leaving the Ivy League and its restrictive policies was given voice in the May 1977 Gazette, and a piece by Marshall Ledger in February 1978 examined the league’s cozy relationship with the NCAA and found that the Ivies were no longer an island unto themselves, but “have shut up and are playing the game.”

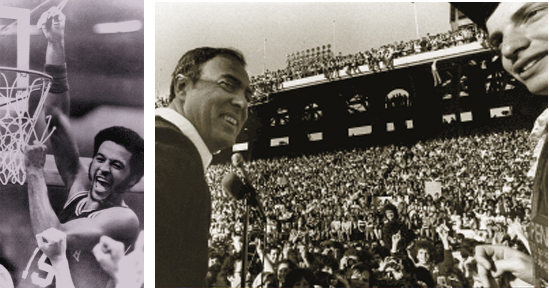

The Final Four and the Football Renaissance

Inarguably the greatest achievement by a Penn team in the last 25 years was the men’s basketball team’s magical ride to the NCAA Final Four in 1979, and the Gazette’s April issue featured expanded coverage of the games and the reaction on campus. Frank Dolson, on loan from The Philadelphia Inquirer, witnessed the team’s galvanizing effect on the University community and observed, “There are people, more than a few of them at Penn, who habitually downgrade sports, who get so caught up in the academic side of university life that they stick up their noses at athletics … There are unique benefits that can be gained from a realistic, honest, successful sports program.”

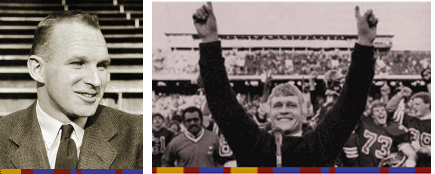

In contrast to the basketball team, Penn’s football program was a laughingstock when Jerry Berndt arrived from DePauw University in 1981. In a feature titled, “Can Coach Berndt Do It?” in November 1981, Marshall Ledger captured the intensity and optimism of the man who would lead the Quakers to the first of four consecutive Ivy titles a year later with a stirring victory over Harvard that remains a watershed moment in Penn sports. “I’d like to be remembered as a coach who came in and regained the tradition at Penn,” Berndt was quoted. “I believe that’ll happen. If it doesn’t happen, if our program stays in the doldrums, I’ll get out.”

Today, with a variety of teams enjoying consistent success in the Ivy League and beyond, Penn athletics is hardly in the doldrums. But do the wins and championships foster a sense of complacency? Have the Ivies become indistinguishable from the rest of the schools in the NCAA? Is it realistic to continue banning athletic scholarships? Will Ivy League schools be able to fund athletic programs without cutting more teams? Those and other questions set the agenda for the next generation of college athletes, and give the Gazette some things to ponder as it begins its second century.

David Porter C’82 is the author of Fixed: How Goodfellas Bought Boston College Basketball and writes the regular sports column for the Gazette.