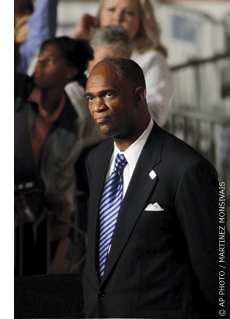

Class of ’77 | Kirbyjon Caldwell WG’77 was in the midst of having it all. It was the late 1970s, and he was back in his beloved hometown, Houston, and on the ground floor of the then-burgeoning bond business. He had his Wharton MBA and a couple of years in investment banking at First Boston in New York on his résumé.

“I was certainly doing well, I have to admit,” says Caldwell.

Yet there was something missing, something deep within him. It wasn’t so much that the life he was living was bad or even shallow; it just wasn’t the right path. He had long thought he would be good in the ministry, and one day, he just decided to up and go that way. He quit his job and enrolled at divinity school at Southern Methodist University.

“I’ve got to tell you, one of the guys I worked with actually cursed me out,” says Caldwell. He is now the Rev. Caldwell, and leader of the 14,000-member Windsor Village United Methodist Church, one of the largest congregations of any sort in the United States, and said to be the largest United Methodist church anywhere. “I knew what I was giving up, a secure financial future, but I knew then, and I surely know now, this is what I was meant to do. And the greatest thing you can do is do what you are meant to do.”

When Caldwell came to Windsor Village, it was, at best, something of an experiment. After a year at another small congregation, Caldwell took over a 25-family church that, while not in the worst section of Houston, was surely on the declining end of the city. It was as if, he says, someone was challenging him—a so-you-wanted-to-be-a-minister-you-business-guy kind of thing.

Caldwell sought to make something of his business background. He often notes that many Bible stories and phrases are attached to business. He sought connections in the Houston commercial and civic worlds to help shore up the Windsor Village neighborhood. Under his aegis, neighbors who became congregants fixed up housing and he, in turn, browbeat politicians to strengthen the infrastructure.

Caldwell, an avid golfer who also played several sports at small Carleton College in Minnesota, also courted celebrity. For a time, sports stars with connections to Houston, like quarterback Warren Moon and boxer Evander Holyfield, became affiliated with Windsor Village.

In time, so did the biggest celebrity in Texas. Seeing a newspaper story about Caldwell, who by that time had been at Windsor Village for nearly a decade and had grown it to about 2,000 families, then-Governor George W. Bush put in a call to Caldwell. The story, which has become Texas legend by now, goes that Caldwell was ready to hang up on what he believed was a prank call—why would a conservative white governor be courting an essentially liberal, if businesslike, black urban minister?—but Bush insisted. In time, they formed a bond through religious faith and mutual need and respect. Bush eventually asked Caldwell to give the benedictions at his inaugurations, and two years ago Caldwell performed the wedding ceremony for the president’s daughter Jenna. Bush has visited Windsor Village several times, and the church’s fame and scope have grown exponentially since the connection between the two men was made.

In the 1990s, Windsor Village took over a K-Mart strip mall and turned it into what Caldwell dubbed “the Power Center.” It grew to have not only worship space, but a medical clinic, classrooms for the local community college, a charter school, office space, an AIDS outreach center, and a branch of the Texas Commerce Bank—no small addition considering that up until then there had been not been a single bank in the neighborhood.

“I hesitate to call it one-stop shopping,” says Caldwell, who has an infectious laugh and can be self-deprecating and, at the same time, confidently proud of his accomplishments. “But if you don’t provide services like this, you can’t expect to heal the soul either. As a minister, my goals have to all be in tune.”

The Caldwell tune, at least politically, changed a bit in 2008. In what he termed one of the hardest phone calls he ever had to make, he told his friend President Bush that he was supporting Barack Obama for the presidency, even to the point of being a “spiritual advisor” to Obama, too, and talking to him about faith about once a week.

Caldwell insists that his decision was not race-based. “Black people have voted for a whole bunch of white people,” he says, adding that he supported more of what Obama stood for than what John McCain stood for.

In conjunction with supporting Obama, Caldwell stayed fairly silent on the subject of homosexuality, which he personally believes is a sin, like adultery and pre-marital sex. A ministry called Metanoia on the Windsor Village website had intimated that with God’s help, “change was possible” for homosexuality—a euphemism for “curing” it. Caldwell says he deleted Metanoia from the website to avoid embarrassing Obama, noting that “you can’t agree on everything.” He and Obama agree that marriage is a union between a man and a woman, he says, and Caldwell accepts that homosexuals have Constitutional rights. He also notes that gay marriage has less acceptance in the African-American community than in the population as a whole.

While he took some heat from other evangelicals, particularly in the African-American community, for his compromise on homosexuality, Caldwell was more irked by the criticism he got after his benediction at Bush’s first inaugural, where he ended his prayer that the Bushes be blessed in their time in the White House by saying: “In the name that’s above all other names, Jesus, the Christ, let all who agree say Amen.” That caused a firestorm, particularly among non-Christians, who claimed it was another sign that the Bush administration was too religion-based and exclusionary. At the time, Caldwell told a Religion News Service reporter: “There does come a time when you need to stake your claim. I always prayed in Jesus’ name. No need to change it now.” When he gave the benediction at the second Bush inaugural, though, he ended it less controversially: “Respecting persons of all faiths, I humbly submit this prayer in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.”

While Caldwell tends to turn the subject away from his presidential connections, he also acknowledges that they can help him, at least in getting notice for what he believes is his main mission: to tend to his Windsor Village community, and that of Houston as a whole.

Caldwell grew up in a black, middle-class section of Houston known as Kashmere Gardens, the son of a tailor father and a high-school guidance-counselor mother. His father had a bit of celebrity in the neighborhood, having made the clothes for a number of local and touring musical acts, among them Houston’s Archie Bell and the Drells. When the Temptations and James Brown came through town, they went to Caldwell’s dad’s shop, and he remembers fondly the night Tina Turner came to the house and tucked him into bed.

After studying economics and government at Carleton College, Caldwell went to Wharton for his MBA. But he came back to Houston, which he characterizes as one of the more vibrant cities in the country.

Jeff Mosely, CEO of the Greater Houston Partnership (which bills itself as the “primary advocate of Houston’s business community”), says that Caldwell has become a big part of the city’s business and educational community, and credits his work with education in Windsor Village and the Houston Independent School District as the inspiration for Governor—and later President—Bush’s No Child Left Behind program.

“He cut through red tape to help people in a side of town that had been underutilized,” says Mosely. “He brought the faith community together with the education community to give those underprivileged more opportunities. Governor Bush was taken by the fact that here was a pastor pushing these concepts and being successful with them.”

Caldwell suggests that his congregation could not care less about his personal celebrity, at least the part that connects him to Bush and Obama.

“I think they really view it as a non-factor,” he says. “I don’t make a lot of it and don’t talk about it. They view me as me, not the friend of someone.”

Caldwell’s current project is to keep expanding Windsor Village’s base. His “calling right now” is a 234-acre planned community on what had been abandoned land near the Power Center. It will include 454 single-family homes and a 121-unit independent living facility. He has gotten commitments from the YMCA, Walgreen’s, Taco Bell, Auto Zone, and a dental center to move in adjacent to his 198,000-square-foot community center.

“This was cow dung and not much else, and now it will be a $181 million enterprise, which is creating jobs for hundreds of people and creating hope for thousands more,” says Caldwell, ever the businessman. “When we did this, we launched a vision, from ground zero to $181 million in seven years. This is value-added. This is what faith is about.”

Caldwell now lives 45 minutes away from his church, which affords him a bit of anonymity and distance. He and his second wife, Suzette Turner—a pastor in the church—have three children, ages 8, 10, and 12. (Caldwell’s first wife, Patrice, was chief of staff for U.S. Rep. Mickey Leland and died in a plane crash with him during a political trip to Ethiopia in 1989. Patrice House, a shelter for abused children at the Power Center, is named after her.)

Though Caldwell has contemplated trying to extend his mission beyond Houston, the city always draws him back. Yet he tells his children that there is no substitute for seeing other places, as he did in college and his first Wall Street job.

“The world is too big and life is too full for you to stay at home unless you have to,” he has told his children. “Let your reach exceed your grasp. I came back, but with a mission, and with experience, and faith, to tell me how best to accomplish that mission.”

—Robert Strauss