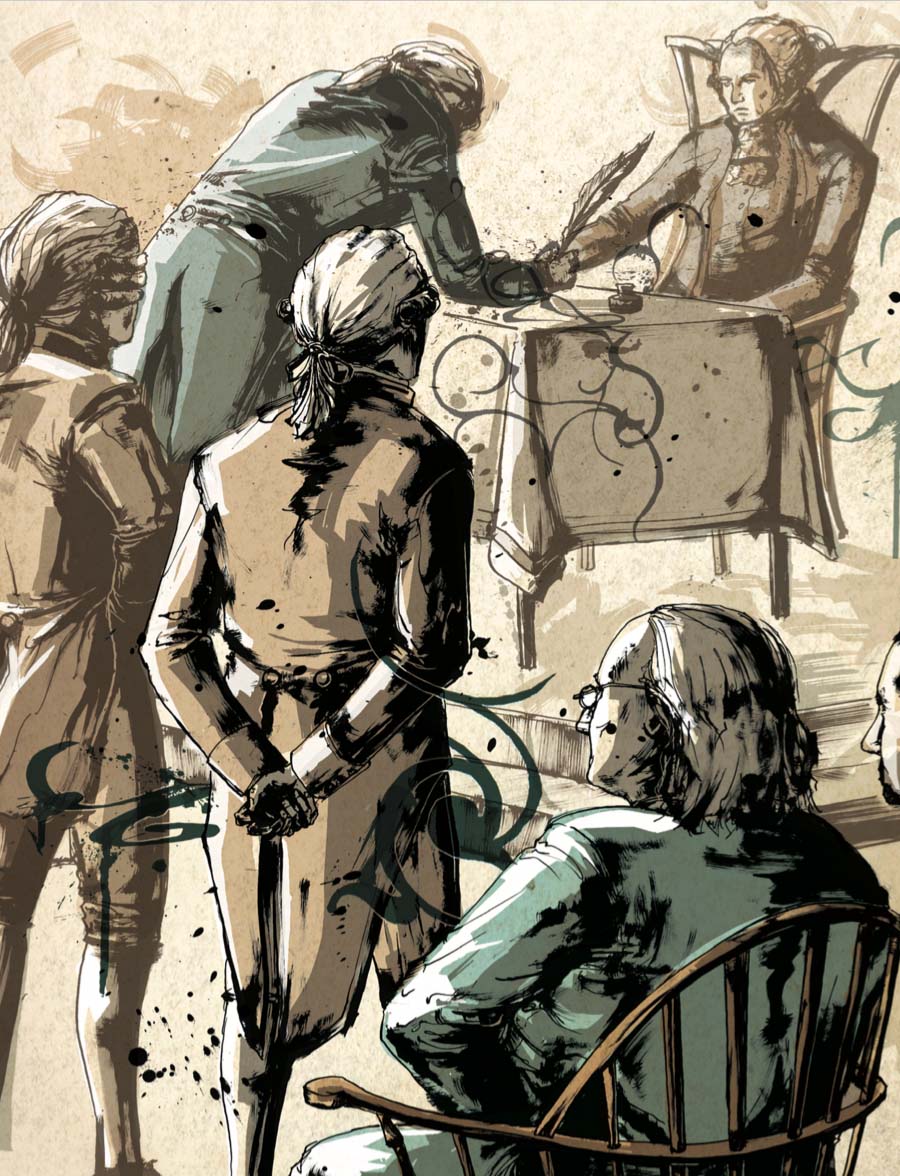

On a crisp September day, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention gathered to sign the document they’d hammered out over the long, hot summer of 1787, flaws and all. An excerpt from Plain, Honest Men by History Professor Richard Beeman. Plus: An interview with the author.

By Richard Beeman | Illustration by Pat Kinsella

Sidebar | Q&A with Richard Beeman

Monday, September 17, brought a crystal clear sky that grew into a deep blue as the sun rose higher. The temperature—barely in the fifties—made it feel more like late fall. But it was a beautiful, invigorating day, and with the exception of the three holdouts—Virginia’s Edmund Randolph and George Mason, and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts—the delegates made their way to the Pennsylvania State House from their private homes and boardinghouses with feelings of anticipation, pride, and profound relief. Forty-one out of the original 55 delegates present at one time or another during that summer were in attendance.

The session began with the Convention’s secretary, William Jackson, reading aloud the full text of the Constitution. The preamble specifically affirmed that this was indeed a constitution—a statement of fundamental principles of government and not merely a collection of articles in a treaty defining the terms under which the sovereign states would enter into a union. By the standards of most constitutions, that of the United States is remarkably short. But after nearly four months, the task of listening to every word of every article, section, subsection, and clause—many of them debated and amended many times over—may have seemed an unnecessarily time-consuming one, clocking in at 32 minutes. Each of the delegates had his copy of the Report of the Committee of Style and, depending on his diligence over the course of the previous few days, could compare handwritten emendations with those read aloud.

That task completed, “Doctor Franklin rose with a speech in his hand,” which, James Madison [whose writings are the main primary source for the delegates’ deliberations] noted, “he had reduced to writing” in order that he could choose his words carefully. Franklin had spent at least some of the weekend composing the speech. His vanity—a minor vice cheerfully acknowledged in his autobiography—may have led him to hope that his would be the final words spoken at the Convention. Whatever his own impulses, it is also likely that Franklin’s Pennsylvania colleagues—especially James Wilson and Gouverneur Morris, but perhaps Virginia’s Madison as well—may have approached Franklin and encouraged him to give the Convention’s valedictory.

Franklin’s very presence at the Convention, along with Washington’s, had given the gathering a weight and legitimacy that it otherwise would have lacked. Washington, who had not delivered a single speech during the formal proceedings in the Assembly Room throughout the entirety of the summer, nevertheless played a crucial role as president of the Convention—guiding the deliberations and making important decisions about whom to recognize and whom to ignore in the give-and-take of debate. In spite of his poor health, Franklin had attended virtually every session from May 28 onward; he had been fully engaged with the proceedings and had spoken frequently. He had gone to the mat on several important occasions, as when on June 30 he presented a version of what would become the Connecticut Compromise, defending it with a wonderful combination of Franklinian insight and simplicity. But he had also allowed himself more than a few moments of self-indulgence, discoursing off the point or offering historical examples not always germane to the issue at hand. His fellow delegates respected and admired him, but at times they must have rolled their eyes heavenward as he launched into one of his digressions.

Franklin rose but then handed the speech to James Wilson, who would read it for his friend and senior colleague. Looking back over the nearly four months of debate, disagreement, and occasional outbursts of ill temper, Franklin observed that whenever “you assemble a number of men to have the advantage of their joint wisdom, you inevitably assemble with those men all their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interests, and their selfish views. From such an assembly can a perfect production be expected?” The wonder of it all, Franklin asserted, was that the delegates had somehow managed to create a system of government “approaching so near to perfection as it does.” Franklin acknowledged there were “several parts of this Constitution which I do not at present approve,” but, he added, “the older I grow the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment and pay more respect to the judgment of others.” And in that spirit, Franklin announced, “I agree to this Constitution with all its faults, if they are such, because I think a general government necessary for us … I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain may be able to make a better Constitution.”

Franklin then appealed to the delegates’ sense of humility and fallibility. “If every one of us,” he warned, “in returning to our constituents were to report the objections he has had to it, and endeavour to gain partisans in support of [those objections], we might prevent it being generally received, and thereby lose all the salutary effects and great advantages resulting naturally in our favor … from our real or apparent unanimity.” He then asked that “every member of the convention who may still have objections to [the Constitution] would, with me, on this occasion doubt a little of his own infallibility—and to make manifest our unanimity—by putting his name to this instrument.”

Franklin’s appeal to the delegates concluded with a formal proposal that “the Constitution be signed by the members [in] … a convenient form, viz. Done in Convention, by the unanimous consent of the states present the 17th of September … In Witness whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names.”

The “convenient form” Franklin proposed—that of asking each delegate to sign the Constitution in recognition of the “unanimous consent of the states present”—was a ploy conceived by Gouverneur Morris “in order to gain the dissenting members.” The dissenting members were not being asked to signal their own approval of the Constitution, but merely to acknowledge that their state delegations had approved it. Morris hoped that this strategy, “put into the hands of Doctor Franklin,” might be sufficient to produce at least the appearance of unanimity.

If the script for the Constitutional Convention had been conceived and directed by a Hollywood filmmaker, Franklin’s speech would have been the final one of the Convention, with perhaps a few gracious closing words from Washington. But this was real life, and so other voices—some supportive and others dissonant—would have to be heard before the Convention could be done with its business. Nathaniel Gorham of Massachusetts now rose with a note of apology in his voice—as if he were aware of the inappropriateness of intruding on Dr. Franklin’s moment—and asked if it might lessen objections to the Constitution if the clause setting the ratio of representation from one to forty thousand was changed to one to thirty thousand. After his motion was seconded by Rufus King of Massachusetts and Daniel Carroll of Maryland, George Washington rose and, incredibly, made the only substantive speech he is known to have made during the whole of the Convention.

He noted that his role as presiding officer had “hitherto restrained him from offering his sentiments on questions depending in the House,” and admitted that the same principle “ought now to impose silence on him.” He nevertheless chose on this sole occasion to speak in support of Gorham’s resolution to reduce the ratio of representation. Washington’s speech was neither eloquent nor forceful. He merely “acknowledged that it [the one to forty thousand ratio] had always appeared to himself among the exceptionable parts of the plan.” Like many in the Convention, he believed that smaller congressional districts would ensure a closer relationship between representatives and their constituents, and he hoped that the proposed change might reduce the number of those opposing the Constitution.

Whatever the personal opinion of the delegates on the relative merits of the two formulas for representation, this was hardly a moment when anyone wanted to pick a fight with General Washington! Gorham’s amendment passed unanimously. It seems unlikely that any of the delegates—even the most disaffected—would vote against Washington on the only occasion on which he had voiced an opinion.

We are still left with the question of why Washington would choose to break his silence on this particular issue. The only plausible answer is that he knew this would be his last chance to speak on a matter on which his words might elicit unanimity among the delegates. He did not want to see the Convention end before seizing that one last opportunity.

But so much for unanimity. Edmund Randolph, plainly uncomfortable about rebuffing Franklin’s conciliatory speech, “apologized for refusing to sign the constitution, notwithstanding the vast majority and venerable names that would give sanction to its wisdom and worth.” He left open the possibility that he might, in the end, support its adoption during the ratification debates, but for the moment, he would refuse to sign because he believed that the people of the states would not accept the Constitution in its present form.

Gouverneur Morris rose to answer Randolph, reminding the delegates that they were being asked to sign the document not as an affirmation of their own individual appraisal but of the unanimity existing among the state delegations present. Echoing Franklin, he admitted that “I too have objections, but considering the present plan as the best that was to be attained, I should take it with all its faults.” The alternative, Morris argued hyperbolically, was the onset of a “general anarchy” across the nation.

The extent of Morris’s reservations about the completed draft remains a point of uncertainty. He is said later to have commented that “I not only took it as a man does his wife, for better, for worse, but what few men do with their wives, I took it knowing all its bad qualities.” That retrospective assessment no doubt contained a measure of truth, but it is likely that at that moment he felt considerable pride at the magnitude of his accomplishment.

Hugh Williamson and Alexander Hamilton echoed Morris in asking the discontented few to put aside their misgivings in favor of unanimity. Hamilton actually had no technical right to sign the Constitution, because the absence of his two naysaying New York colleagues, Yates and Lansing, meant that New York was not even entitled to vote on the document. This did not, however, stop him from making his own speech urging all of the delegates to sign and, when the time came, stepping forward and affixing his name to the document. Hamilton warned ominously that a “few characters of consequence by opposing or even refusing to sign the constitution, might do infinite mischief.” Acknowledging his position at the far right of the political spectrum, he reminded the delegates that “no man’s ideas were more remote from the plan than his own were known to be; but it is possible to deliberate between anarchy and convulsion on the one side, and the chance of good to be expected from the plan on the other.”

At least one delegate, William Blount of North Carolina, was brought into line by the strategy conceived by Morris and articulated by Franklin. Following Hamilton’s speech, Blount announced that though he had not intended to sign the document, “I am relieved by the form proposed and will without committing myself, attest to the fact that the plan was the unanimous act of the states in the Convention.”

Randolph, Mason, and Gerry would stand their ground. Randolph was obviously torn, and possibly repentant. As Madison recorded Randolph’s final words on that day, “In refusing to sign the Constitution, I take a step which might be the most awful of my life, but it is [a step] dictated by my conscience, and it is not possible for me to hesitate, much less, to change.” Elbridge Gerry, though admitting “the painful feelings of his situation,” was more combative in reiterating his objections. Gerry, along with Mason, was still clinging to his old classical republican fears. With the tumult of Shays’ Rebellion still in mind, he continued to worry “that a Civil War may result from the present crisis of the United States.” The source of that crisis, Gerry believed, was the clash of two opposing parties, “one devoted to democracy, the worst of all political evils, the other as violent in the opposite extreme.” It was for these reasons that he had supported the idea of a Convention, but he now concluded that the final result of the Convention combined some of the worst elements of each of the two extremes. Unlike Randolph, who seemed genuinely pained not to join Franklin (not to mention his fellow Virginian, George Washington, whom he had literally begged to come to the Convention), Gerry appeared to resent Franklin’s remarks, commenting acidly that “I cannot … but view them as leveled at myself and the other gentlemen who meant not to sign.”

Franklin’s speech had accomplished as much as it could, but no more. It had brought William Blount into the camp of those willing to sign the Constitution, but two South Carolina delegates, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Pierce Butler, “disliked the equivocal form of the signing” proposed in Franklin’s motion. On that note of mild discord, the delegates voted on Franklin’s motion. “Done in Convention by the unanimous consent of the States present the 17th of September … In Witness thereof we have hereunto subscribed our names.” Franklin’s motion passed, with 10 states in favor and South Carolina divided.

Before proceeding to the formal signing, the delegates spent several minutes trying to decide what to do with the official journals of the Convention that were kept, however haphazardly, by William Jackson. The delegates’ fear, as Rufus King expressed it, was that “if suffered to be made public a bad use would be made of them.” The two suggestions put forward were either to destroy them—a decision that would have made the scanty Convention record even scantier—or to deposit them in the custody of the president of the Convention. The delegates agreed to the latter scheme by a vote of 10 states to one, with the Maryland delegates objecting because they had been explicitly instructed by their legislature to report the proceedings of the Convention back to their state.’’

This left the “president,” General Washington, in a bit of a quandary. What was he supposed to do with the Convention papers, and what if members of the Convention asked him for copies? The delegates ultimately decided that Washington should hold the papers under conditions of strict secrecy until a “Congress, if ever formed under the Constitution,” could give him further instructions. Washington would officially convey the journals of the Convention to the Department of State in December 1796, just before he left office as president, and the Congress continued to impose a prohibition against publishing them until 1818.

Left unresolved was what the other delegates would do with their materials from the Convention. Nearly all of the delegates had, with varying degrees of diligence, retained copies of the various drafts and reports that had been produced by the Convention, and several had made notes along the way. The most thorough of these were produced by Madison, who had taken extraordinary pains to record the proceedings. Remarkably, given the size of the egos and the diversity of personalities present at the Convention, the delegates who had kept their own diaries and notes during the Convention kept their resolve as well, waiting until the Congress lifted its ban on their publication. From that time forward, bit by bit, various delegates—or their descendants—began to make portions of their notes public.

Again, Madison presents the most interesting case. He began to review his notes and make revisions, entering into an active correspondence with a number of key figures, soon after the Convention journals were published in 1819. However, he remained true to a pledge he had made to himself—to withhold the publication of his notes until after his death, in 1836.

“The members then proceeded

to sign the instrument”

With those simple words, Madison recorded the epochal event of the Constitutional Convention. At about three in the afternoon, beginning with the New Hampshire delegates, moving southward to Massachusetts, then progressing down the eastern seaboard, and ending with Georgia, the delegates moved to the table at the center of the east wall of the Assembly Room where Washington had presided, picked up the goose quill pen, dipped it in ink, and signed their names to the document. All of those who stepped forward to sign the fourth of the parchment sheets shared in varying degrees the same tentativeness and diffidence so eloquently (and cleverly) described by Franklin in his speech earlier in the day. They all believed they had framed a document that would create “a more perfect union,” but no one believed that they had achieved perfection.

Among the ardent nationalists, Gouverneur Morris still believed that too much authority had been left with the state governments and too much power within the new government had been given to the small states. Alexander Hamilton was of much the same mind. He no doubt thought the Constitution too republican and insufficiently British in its inspiration.

The two Connecticut delegates still present at the Convention, Roger Sherman and William Samuel Johnson, had considerable cause for pride. Their intervention helped produce the compromise between large and small states, and they had successfully moderated some of the more extreme impulses of the most zealous nationalist delegates. For better or for worse, they had played a key role in brokering the compromise that provided protection for the slave states of the lower South. Yet Sherman, who had consistently argued for an executive authority that would merely be the agent of the legislature, must have still harbored fears about the overly powerful presidential role created by the Constitution.

William Paterson had left the Convention on July 23, and in spite of entreaties by his fellow New Jersey delegates to return, he had resolutely refused. He managed, however, to summon up the energy to make the short trip across the Delaware River from Trenton to Philadelphia in time to sign the document on September 17. Although he had grudgingly abandoned his attachment to his own New Jersey Plan and voted in favor of the Connecticut Compromise, he was still not wholly reconciled to the diminution of state equality and power inherent in the Constitution. As a testimony to how time, and success, can change one’s perspective, Paterson would deliver orations just a few years later in which he would take pride in his role in drafting the Constitution and praise it as “the ark of safety and the palladium of our liberties.”

As the delegates from the slave-owning states moved forward to the president’s table, they were hardly of one mind about the virtues and imperfections of the Constitution. Many delegates from both the upper and lower South continued to worry that Congress’s power to regulate commerce by a mere majority vote would work to the disadvantage of the agricultural-staple-producing states. But whatever misgivings individual delegates from the slave-owning states may have harbored, most of them had spoken consistently on the side of a stronger federal union. Moreover, the South Carolina and Georgia delegates—with help from some of their colleagues to the North—had managed to write into the Constitution protections for slavery that would work decisively to their advantage for years to come.

The two most prominent Virginia signers—James Madison and George Washington—were reserved in their assessments of the finished product. At the end of his life, looking back on the events of that summer, Madison would characterize the conduct and outcome of the Convention in extravagant terms, claiming that “collectively and individually … there never was an assembly of men, charged with a great and arduous trust, who were more pure in their motives or more exclusively or anxiously devoted to the object committed to them than were the members of the Federal Convention of 1787.”

Yet at the moment Madison stepped forward to sign the Constitution, his pride in his accomplishment was almost certainly tempered by the sting of at least a few defeats. He was disappointed that the feature giving the federal government a negative on state laws had been deleted from the Constitution, and he continued to feel deeply aggrieved about the compromise that had given the smaller states equal representation in the Senate. He persisted in believing that the Connecticut Compromise was a serious blow to the fundamental principle that the new government was to be directly representative of the people of the nation and not of the states. He was acutely aware that he had not achieved all that he had wished when he first set out to launch his revolution in government. But those misgivings notwithstanding, the real wonder is that he had achieved as much as he did.

George Washington, though a member of the Virginia delegation, had, as president, been the first to sign. His diary entry for September 17 tells us less about his feelings about the Constitution itself than about the arduousness of the process. After the Convention adjourned, he dined with the delegates at City Tavern and then returned to his lodgings, where, after receiving the Convention papers from William Jackson, he “retired to meditate on the momentous work Which had been executed, after not less than five, for a large part of the time six, and sometimes 7 hours sitting every day [except] Sunday … for more than four months.”

Dr. Franklin would, after all, have the last word. As the line of delegates waiting to sign the Constitution was nearing its end, the old philosopher-statesman looked up at the Chippendale-style chair Washington had occupied during that summer. Fashioned by a local cabinetmaker, John Folwell, it had a red leather seat and a high back—on the center of which was carved a half-sunburst—and was topped by a Phrygian Liberty cap on a pike, an ancient Roman symbol of freedom. As the final delegate—Abraham Baldwin of Georgia—added his name to the list of signers, Franklin’s attention turned to that sunburst.

Although too frail to rise from his chair, Franklin spoke in his own words on this occasion. He confided to the delegates that he had, “in the course of the session, and the vicissitudes of my hopes and fears as to its issue,” gazed at the sunburst on the back of the president’s chair “without being able to tell whether it was rising or setting.” With a note of deep satisfaction, Franklin announced that “now at length I have the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting sun.”

Excerpted from Plain, Honest Men by Richard Beeman. Copyright © 2009 by Richard Beeman. Excerpted by permission of Random House, a division of Random House, Inc.

SIDEBAR

Q&A with Richard Beeman

“What I so love about this book [is] it’s a great narrative, a great yarn, great personalities, but you’re not afraid of legislative minutiae.”

That’s what The Daily Show’s Jon Stewart had to say about Richard Beeman’s new book on the making of the U.S. Constitution, Plain, Honest Men, which is excerpted in this issue. Stewart concluded his mostly respectful April 23 interview with the Penn professor of history and former College dean by calling the book “a great and thorough telling of the story.” (On the other hand, he opened the show by pretending to think his guest that night would be “supervillain Bee Man—half man, half bee.”)

This summer Beeman also answered some questions, posed by Gazette editor John Prendergast, about how he came to write Plain, Honest Men, what the delegates to the Convention got right and wrong, and his “out-of-body-experience” on The Daily Show.

You say in the acknowledgements that, though you’ve been studying and writing on the Constitution for 40 years, this is the first book you’ve done on it designed for a wide audience. What was the impulse that led you to write it and why did you think such a book was needed?

The subject of the Constitutional Convention has fascinated me ever since I read Catherine Drinker Bowen’s popular account, Miracle at Philadelphia, more than 40 years ago. Bowen’s book is a terrifically good read, but as I have thought about the subject over the years, I have come to realize that her book tends to mythologize the Founding Fathers, to elevate them to the status of demi-gods, rather than portray them as the practical-minded, 18th-century politicians that they were. So I wanted to have my say on the subject. And though I have had the pleasure of teaching many hundreds of Penn students about the Convention over the course of my 41 years on the faculty here, my participation in the design and creation of the National Constitution Center—whose exhibits reach hundreds of thousands of American citizens each year—inspired me to try to write a book that would convey my thoughts on this important subject to a much wider audience.

You call Madison, Washington, and Franklin the “indispensable men” of the Convention. Madison and Washington’s central roles are clear, but can you talk about Franklin’s? In the narrative, he seems out of it much of the time, with the other delegates almost humoring him.

For much of the Convention Franklin’s intervention in the debates is uneven at best, and sometimes downright wacky (as in his suggestion that justices of the Supreme Court be elected by a vote of all the lawyers in the country). But on the final day of the Convention, in his speech asking the assembled delegates to put aside their sense of their own “infallibility” and to sign the completed document, with all of its perceived flaws, Franklin dispenses an essential bit of wisdom that could serve as sound advice for any group of politicians—particularly, perhaps, our national Congress today.

The book is basically a day-by-day account of the Constitutional Convention, from May to September 1787, and one of the strengths of that detail is that it becomes clear how much the document was created on the fly, so to speak. It’s not like the group convened to ratify something that had been worked on in advance—they really made it up as they went along. Can you talk a bit about the audacity of that process?

The “audacity” of the process occurs at the very beginning, when James Madison and a few key members of the Pennsylvania delegation cook up the Virginia Plan, a plan to scrap the Articles of Confederation altogether and to start over with a truly national national government, with a supremelegislature, executive, and judiciary. That plan called for a true revolution in the character of America’s continental government. Although the Virginia Plan did not survive intact, it did set the agenda for the remainder of the Convention, setting the delegates on a course not merely to amend the Articles of Confederation, but to establish an entirely new kind of central government. After that audacious moment (which occurred on May 29, when Virginia Governor Edmund Randolph presented the Virginia Plan) the process of constitution-making was less about either great flights of imagination or divine inspiration, but rather, was hard, often tedious work.

What were some of the disadvantages? In some ways, decisions seemed to be arrived at through exhaustion. But would more time have helped?

More time??!!! From the standpoint of the Convention delegates, that summer in 1787 seemed nearly endless. If anyone had suggested that they spend still more time confined to the Assembly Room of the Pennsylvania State House, the delegates would have shrieked with horror. As it was, when George Mason of Virginia, in early September, proposed that the delegates add a bill of rights to the Constitution, nearly all of the delegates ignored his suggestion, fearing that a discussion of such a bill of rights would prolong their confinement still further. As it turned out, that bit of impatience was a serious mistake on their part, for when the document was submitted to the people of the states for approval, there was widespread agreement that the absence of a bill of rights was a serious defect.

The Convention’s deliberations were kept secret—with a high degree of success, as it turned out. How did that affect the course of events?

The rule of secrecy was enormously important to the success of the Convention. Over the course of that long summer the delegates disagreed, often vehemently, over many of the proposals put before them. The rule of secrecy allowed them to engage in spirited debate and disagreement, and then to go off that evening to the tavern, enjoy a cordial meal and a drink (actually, copious quantities of drink) together, putting aside their differences of the day, knowing that they would return the following day to try to reach consensus.

The rule of secrecy was of course totally contrary to our modern political ethic—it was both undemocratic and untransparent. But imagine if we were to hold a Constitutional Convention today, with each delegate staking out his or her own position, posturing before the television cameras, carefully prepared with his or her sound bites when confronted by the reporters from Fox News or MSNBC. The ability to “doubt a little their own infallibility,” so perceptively championed by Franklin, would be altogether absent. I shudder to think of the consequences.

A lot of the early controversies among the delegates based on small state versus large state issues seemed to be beside the point in the later history of the country. But the arguments related to slavery obviously continued to figure—and would ultimately nearly tear the country apart in the Civil War. Were the delegates’ attitudes toward slavery their greatest blind spot?

Absolutely. The delegates’ failure to confront the “paradox at the nation’s core” may have allowed them to move forward with their business, but by postponing the day of reckoning over that paradox, it added hugely to the suffering and bloodshed that would follow in the decades to come. The reasons for the delegates’ failure are complicated—too complicated to summarize in a brief paragraph. This is the point at which I ask, shamelessly, your readers to buy and read the book!

There are other elements that we are still arguing about—for example, the extent of executive power, and the notion of “original intent” in interpreting the Constitution. What would the delegates have thought

of that?

Americans have been arguing about how their Constitution should be interpreted since the day the delegates began debating the Constitution on May 25, 1787, and we continue to do so today—especially today. But unlike many contemporary jurists (Justice Scalia does come to mind here), they were extraordinarily humble about their accomplishments. They would have been loathe, I think, to demand that subsequent generations of Americans be bound by their conceptions of any of the particular provisions of the constitution they had drafted. Indeed, they knew full well the extent of the divisions that existed among them about the meaning of key aspects of their constitution—on the precise meaning of “federalism” or “executive power.” With all due respect to those who espouse either an “originalist” or an “original intent” doctrine of constitutional interpretation, I believe that the framers of the Constitution would have found either notion to be chimerical.

If you had to say, what would you judge as the main thing the Constitutional Convention got right, and what was the most important thing they got wrong—aside from their essential indifference to slavery, which is in a class by itself?

The delegates faced the same task that has confronted virtually every society since the beginning of time—that of devising a mode of government that would preserve public order while at the same time granting to individuals an appropriate measure of personal liberty. But that task was made particularly formidable by the very character of America—its geographic expanse, its ethnic and religious diversity, and the jealousies of each of the independent and autonomous states. In devising a system of government that provided both checks and balances within the new government and for a division of power (however vaguely defined) between the central and state governments, the framers succeeded brilliantly. But most of the framers of the Constitution were republicans, not democrats, and many of the features of the government they created—an indirectly elected Senate and the electoral college come immediately to mind—provide pretty clear evidence that they had succeeded only in creating a more perfect union, not a perfect union.

What would you like people to take away from the book?

A simple truth. Good government requires hard work—both in the creation of the government and in its execution. And it requires a good deal of humility—the ability to check one’s ego at the door and to not allow the perfect to become an enemy of the good. That was Franklin’s essential wisdom, dispensed on that last day of the Convention.

Finally, Plain, Honest Men has received a good deal of attention, including a positive review in The New York Times by Franklin-biographer Walter Isaacson. But for a certain segment of our readers at least, your appearance on The Daily Show was the only publicity that really mattered. What was that experience like for you, and what impact did it have?

I have described my interview by Jon Stewart on The Daily Show as an “out-of-body-experience.” I was terrified at the prospect and I honestly have little memory of what I actually said in response to his questions. But, somehow, all that information that I had in my head about this subject didn’t evaporate, the neurons in my brain seemed not to misfire, and I managed to escape without major public humiliation.

The effect of The Daily Show appearance was amazing. It is perhaps a commentary on the state of our republic that a highly favorable review in the The New York Times by a distinguished author caused book sales to increase slightly, but my six and a half minutes on The Daily Show caused sales to skyrocket! And, from the standpoint of Penn undergraduates, an appearance on The Daily Show seems to have had made a far greater impression than, say, if I had been awarded a Nobel Prize.