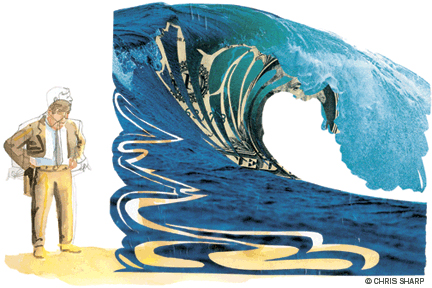

America’s economic system is facing ugly weather—but there’s still time to avoid it.

By Laurence Kotlikoff

Imagine the United States in the year 2030:

The country’s collective population is older than Florida’s today. There are twice as many retirees—but only 18 percent more workers to support them.

The government is in desperate trouble. It’s raising taxes sky high, drastically cutting retirement and health benefits, slashing defense, education, and other critical spending, and borrowing far beyond its capacity to repay. Tax evasion is rampant, inflation is high and rising, the underground economy is growing and the currency is depreciating rapidly. Political instability. Unemployment. Labor strikes. Rising crime rates. Record-high interest rates. Financial markets in ruin.

In short—a future in which America is plunging headlong toward Third World status.

Think things can’t get that bad?

Lots of people, particularly those running for reelection, would agree. Their tranquilizing view runs like this: “Yes, the nation will be older, but our fiscal affairs and the economy will be just fine. The country’s deficits are modest relative to the size of the economy and will decline through time. Social Security has some problems, but the system is close to 75-year actuarial balance. The same holds for Medicare. The government can always cut fat. Technological change will bail us out. And we can always bring in more immigrants to pay our bills.”

These and other comforting ways of resolving the nation’s aging dilemma are either wrong or small potatoes when set against the fiscal imperatives of 77 million Baby Boomers’ outstretched hands. There is no economic or demographic magic wand. Bad things do happen to good countries, and we are heading into one God-awful fiscal storm.

There’s still time, however, to get out of its direct path and avoid the full brunt of its impact. Doing so will require major sacrifices, real statesmanship, new ideas, and, above all, a consensus that we’re facing a grave economic danger.

The U.S. has a deficit of $51 trillion, and we are making matters worse by cutting taxes, expanding Medicare benefits, and growing the government sector, particularly the military, much faster than the economy as a whole. None of those trends is likely to change. Our only real hope lies in reforming Social Security and Medicare, whose combined unfunded liabilities account for almost all of that red ink.

Social Security, which accounts for $7.2 billion of the fiscal gap, was established in 1935, smack dab in the middle of the Great Depression. The program’s primary objective—securing the economic welfare of the elderly—was and remains a perfectly laudable goal. But the program had very serious design flaws, exacerbated over the years by patchwork provisions and piecemeal reforms: It systematically provides benefits to certain individuals who neither need nor deserve this support, generates major work disincentives, leaves workers with little idea of what they are getting in exchange for their tax contributions, and cannot guarantee the payment of the benefits it calculates.

Fixing these equity, incentive, information, and risk problems, as well as securing Social Security’s finances, are objectives that any reasonable person should support. When it comes to Social Security, however, our politicians aren’t particularly reasonable. Republicans would repair Social Security by eliminating it, while Democratic politicians react with abject horror to the system’s potential “privatization” and sic AARP’s 35 million elderly voters on anyone who breathes the words “Social Security reform.”

Nevertheless, financial reform of Social Security is imperative, and structural reform is long overdue. To this end, my colleague Scott Burns and I propose what we call the personal security system. We think that this is the system most Social Security experts would choose were we able to set up the system from scratch.

The PSS plan is short, with 11 provisions that fit on a postcard (which seems to match the attention span of most politicians). The second thing to note is that the plan shuts down, at the margin, the retirement, or Old Age Insurance (OAI), portion of Social Security. Current retirees continue to receive their full OAI benefits, and current workers receive, in retirement, all the OAI benefits owed to them as of the date of the reform. But once the reform is implemented, the accrual of additional OAI benefits is history.

We pay off what we owe, but that’s it.

For workers close to retirement, their accrued Social Security retirement benefits are very close to what they’d receive under the current system. But for today’s young workers in their 20s and 30s, their accrued Social Security benefits are fairly small. This means that over time (about 45 years), the aggregate amount of Social Security benefits that will need to be paid each year will decline to zero.

The plan doesn’t mess with either survivor (SI) or disability (DI) benefits, leaving in place the payroll taxes needed to finance these two programs. It does eliminate the OAI payroll tax, but workers would contribute the money to PSS accounts instead while a new federal retail-sales tax would pay off OAI benefits during the transition. Since the total amount of OAI benefits would gradually decline to zero, this tax, which would start out at roughly 12 percent, would also phase out through time, although not to zero.

Before anyone starts screaming that a sales tax is regressive and will hurt the poor, remember that sales taxes are in part wealth taxes because when rich people spend their wealth to buy caviar, BMWs, yachts, and facelifts, they end up spending part of their wealth on taxes. Also, the elderly poor living solely off Social Security will be completely insulated from its effects. When the tax raises consumer prices, the Social Security benefits of the poor—and everyone else—will be automatically adjusted because they are indexed to inflation.

The young and middle-aged poor will have to pay the sales tax—but they will be spared having to pay the OAI payroll tax. Ask yourself whether a minimum-wage worker would prefer to pay 12.4 percent of her wages in Social Security payroll taxes now, with the prospect of that tax rate doubling over time, or a 12 percent sales tax now, with the sure knowledge that the sales-tax rate will decline to around 3 percent as the accrued retirement benefits owed by the old Social Security system are paid off and head to zero.

Apart from the elderly poor, the tax hits everyone—old and young, and rich and poor. This is much different from the existing payroll tax, which is paid only by young and middle-aged workers and only up to a ceiling ($90,000 in 2005).

The PSS protects nonworking spouses, spouses who are secondary earners, the disabled, and the unemployed. Married workers would have to split the contributions fifty-fifty with their spouses, so each would end up with an equal-sized PSS account, while divorced spouses walk away with their own accounts. The government would make matching contributions to PSS accounts on a progressive basis. The new retail-sales tax would finance these matching contributions as well as cover contributions on behalf of the disabled and unemployed.

PSS account balances would be invested in the global financial market, but the government would insure the downside of this investment: It would guarantee that workers never lose the principal that they invest in their accounts. All account balances would be invested in a single security—a global index fund of stocks, bonds, and real estate. Foreign stocks and bonds are included for diversification. By investing abroad, the fund will lower the riskiness of the return of the PSS index without lowering its average return.

The PSS reconciles the minimum requirements of both political parties. The Republicans get a fully funded retirement saving system that’s invested in the market. The Democrats get a system that is equitable, as they define equity, and that protects workers from the downside risk of investing in volatile financial instruments.

Each participant’s account balances would be sold starting at age 57 and continuing each day for 10 years. By liquidating PSS balances in this very gradual manner, there is much less risk of selling when the market is temporarily low. Participants would receive inflation-projected pensions (annuities) starting at age 62 reflecting the proceeds of all account balances sold prior to age 62. Finally, all nonannuitized PSS account balances would be bequeathable.

The PSS puts everyone in the market and limits the downside risk of investing. It precludes huge Social Security payroll tax hikes. And it distributes the burden of paying off benefits owed by the old system fairly and squarely.

There is a way out of the storm. It involves fundamental reforms of Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid; the enactment of a new retail-sales tax; the elimination of the unaffordable tax cuts; and restraining discretionary spending. None of these steps will be easy, but each is essential if we hope to preserve the American dream for our children, grandchildren, and generations to come.

Dr. Laurence Kotlikoff C’73 is a professor of economics at Boston University and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. He is co-author with Scott Burns of The Coming Generational Storm: What You Need to Know About America’s Economic Future (The MIT Press, 2004). This essay was adapted from the paperback edition, issued by The MIT Press in 2005.