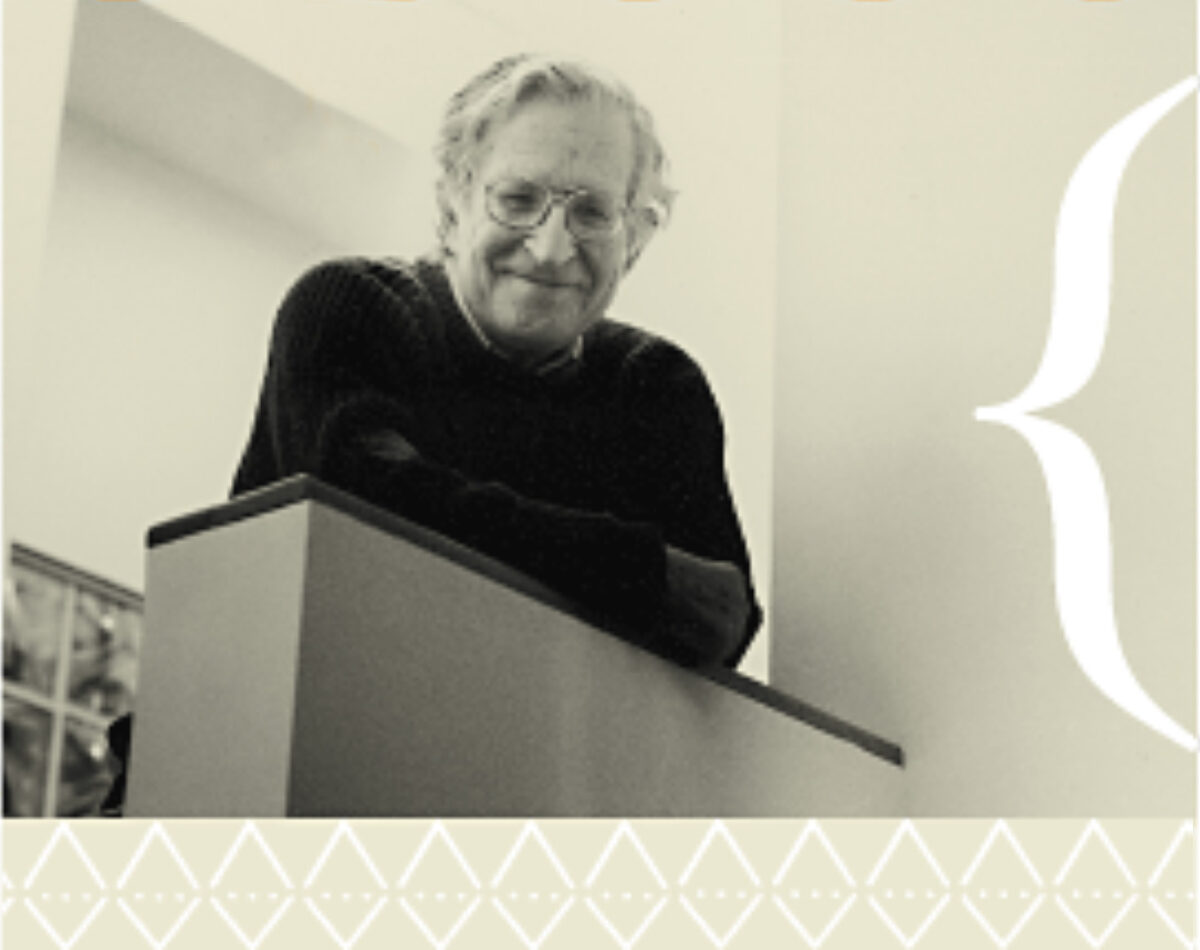

More than a half century after he nearly dropped out of Penn, Noam Chomsky towers over the field of linguistics and the politics of dissent. What would have happened if he hadn’t met Zellig Harris?

By Samuel Hughes | Photography by John Soares

Sidebar | The Way They Were (and Are)

Not-not-not. A hand raps lightly on the office door.

It’s the universal grammar of Knuckle, a language that goes deeper than human speech. Dr. A. Noam Chomsky C’48 G’51 Gr’55 Hon’84 glances over his shoulder and emits an utterance to the rapper: “OK, just a minute,” which turns out to mean something like, “Come back in five or 10 minutes and try again.” Then he revs up his language module and the quiet torrent of words resumes, his discourse segueing effortlessly from the structure of cognitive systems to the degradation of classical liberalism to Eugene Debs and the crushing of the labor movement to Richard Nixon’s dismantling of the Bretton Woods international economic system to the World Trade Organization’s next meeting in Qatar to the totalitarian nature of corporations to—

NOT-NOT-NOT. The meaning of this second Knuckle discourse is clear even to someone who has never heard the dialect before. Chomsky again says that he’ll be done in “just a minute,” which this time I translate to mean, “I know this chowderhead is taking advantage of my generosity, but since he came all the way up from Philadelphia, let’s cut him a little slack.”

The knuckles belong to Bev Stohl, Chomsky’s personable assistant and, um, temporal structuralist. She reigns supreme in the outer office of the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy at MIT, where Chomsky is the Institute Professor of Linguistics. Even legendary anarchists sometimes need a firm hand and a system to save them from their own discursive effusiveness.

A question: Given that he pretty much changed the course of linguistics and the cognitive sciences with his theory of a “language faculty” inherent in all humans, does it ever strike him as ironic that his own language faculty borders on the superhuman?|

“No,” he says mildly, twisting a small piece of paper in his fingers. “I don’t particularly like speaking. It’s one of those things which I never intended to do.”

Hmm. That would explain the barely audible voice and the initial hesitancy to accept yet another interview request. (His schedule is booked months in advance, and he turns down several interview requests each day.) But it should not be taken to mean that he stumbled blindly into his second career as a public intellectual and high-profile dissident.

“I remember very well deciding whether to make that move,” he says, pinpointing the decision to about 1960. “You can’t get into these things casually. If you get involved, it’s going to be very demanding, and more than a full-time life. You either do it seriously or you don’t do it at all.”

Chomsky, by any definition of the word, does it seriously. In Poland, some people assumed there were two Noam Chomskys: the seminal, prolific linguist and the seminal, prolific dissenter. The notion that one man could be both was apparently incomprehensible. Even now, this 72-year-old grandfather of four shows few signs of slowing down. Dr. Lila Gleitman G’72 Gr’75, the Steven and Marcia Roth Professor of Psychology and professor of linguistics at Penn and an old friend of Chomsky’s, may have figured out his secret. She thinks it’s “unfair that he has 30-hour days and the rest of us only have 24-hour days.”

Years ago, someone wrote in The New York Times that, “Judged in terms of the power, range, novelty and influence of his thought, Noam Chomsky is arguably the most important intellectual alive.” The line is irresistible for anyone writing a story about him, though Chomsky himself—a frequent critic of the Times (and most other mainstream news media)—likes to point out that the next, less-quoted sentence is: “Since that’s the case, how can he write such terrible things about American foreign policy?”

His own writing never appears on the op-ed page of the Times or any other mainstream newspapers, which helps explain why so many people vaguely recall his name but know nothing else about him. This doesn’t seem to bother him too much. Being relegated to the political margins is proof of his Propaganda Model—in which various “filters,” most of them economic, ensure that the mass media play a propagandistic role.

“In the United States, what I say should be marginalized,” he once said. “In fact, if I stopped being marginalized, I’d rethink what I’m doing.”

And yet: according to a recent survey by the Institute for Scientific Information, only Marx, Lenin, Shakespeare, Aristotle, the Bible, Plato, and Freud are cited more often in academic journals than Chomsky, who edges out Hegel and Cicero. “He is staggering in his productivity,” says Dr. Edward Herman, the emeritus professor of finance who has collaborated with Chomsky on books and essays about politics, including Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. “He’s also an incredibly generous man with his time.”

Search Penn’s on-line library catalogue under author: chomsky noam and no fewer than 98 titles appear. That includes a few duplications, as well as interview collections like Keeping the Rabble in Line (with David Barsamian), but it doesn’t include biographical works like Chomsky for Beginners (whose cover depicts the donnish professor as a superhero, complete with a cape and a red N on his chest) or Robert Barsky’s Noam Chomsky: A Life of Dissent(which can be downloaded off the Internet). Several massive Web sites devote themselves to his on-line output, including Bad News: Noam Chomsky, which modestly describes itself as “sort of a supplement to the far more essential Noam Chomsky Archive.” Various documentaries of his speeches and interviews are available on video, including Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media, a two-part video documentary which chronicles Chomsky’s efforts to impart some “intellectual self-defense” against what he sees as the power-serving manipulations of most news organizations.

Demonstrating a link between his linguistic theories and his political views is easier said than done. Some say that his generative-language theory emphasizes a common—and creative—human heritage, an honorable liberal notion. While he is politically a man of the left, I suggest, the notion of a genetic language faculty seems to run counter to the (usually) left-liberal view that environment, not heredity, is what most shapes humans.

“That has been assumed, but I don’t think it makes any sense,” he says quietly. “For one thing, the idea that your cognitive systems are biologically unstructured is just insane. The only question is why anybody believes it, since it’s so obviously outlandish. And I certainly don’t think it has anything to do with the left. In Cambridge in the 1950s, the few of us graduate students who did not accept the prevailing, largely behaviorist orthodoxy were all on the left. And the ones who most advocated it were people who were extremely reactionary. I don’t draw any particular conclusions from that, just to point out it’s not a left-right issue.”

NOT-NOT-NOT. Three knuckle-strikes and you’re out, I figure, and shut off my tape recorder. As we get to our feet and step through the door leading from his office, I mention ruefully that we got to about half the questions on my list. “You can always send me some more by e-mail,” he says gently, and we shake hands goodbye. I take him up on his offer, which makes me part of the problem: some of his e-mails are almost 4,000 words long.

Noam Chomsky, in particular, says flatly and often that he has very little concern for language in and of itself; never has, never will. His driving concern is with mental structure, and language is the most revealing tool he has for getting at the mind.—Randy Harris, The Linguistic Wars.

It’s been more than 40 years since Chomsky first kicked open the door of linguistics with his theory of generative grammar and a human language faculty. Most of his work since then has essentially been refining and deepening that theory. (He now refers to the language faculty as the “I-language,” Istanding for internal, individual, and intentional.) And yet he remains the 800-pound gorilla in linguistics, the one whose work every student has to deal with, and whose dominance in the field is often compared to the relative dominance of people like Einstein and Freud.

“Doing linguistics for the last 40 years is a matter of agreeing or disagreeing with Chomsky—contributing to that program, or trying to contribute from a slightly different perspective,” says Lila Gleitman. “But he won’t go away. He set the agenda; he was a great technical contributor; and he was a great empirical contributor. So at many, many levels, he just dominated the field and pervaded the field.”

“He has transformed not just linguistics but the whole of cognitive psychology,” says Anthony Kroch, professor and chair of linguistics. “He hasn’t done it alone, and it will take a while for people to understand what was happening.”

Kroch, who received his doctorate from Chomsky’s department at MIT in the early ’70s but was not interested in becoming an acolyte, later performed an analysis of historical syntax in 16th-century English. He thought the data he was using would pose a challenge to Chomsky’s generative paradigm—until he analyzed it.

“The work I did in the early ’80s made me appreciate in a personal way what an impressive thinker Chomsky was, because I had started out to prove him wrong, and I had succeeded in proving him right—or at least the data made more sense if I believed him than if I disbelieved him. And that’s convincing in a way that no amount of just listening to somebody else could possibly be.”

Was Chomsky pleased with Kroch’s findings, I wonder, or was he indifferent because he knew he was right to begin with?

“I think the latter,” Kroch answers quickly. “You could say, ‘Well, arrogant son of a bitch,’ and so on. But remember what Einstein said when people went and measured the perturbations in the orbit of Mercury, and somebody asked him, ‘What would you have said if it had come out the other way?’ Einstein said, ‘I would have said that they made an error.’ That sounds very arrogant, but once you know something really deeply, you sort of know it. And I think Chomsky had reason to think that he had really got hold of something.”

The young man who would become arguably the most influential intellectual ever to graduate from Penn nearly dropped out his sophomore year. By then it was 1947, and Chomsky was commuting from his parents’ house in the East Oak Lane section of Philadelphia and teaching Hebrew School on the side. His father, Dr. William Chomsky, was the head of the Hebrew School system in Philadelphia, and a respected Semitic philologist who wrote a book on medieval Hebrew grammar.

In his spare time, Noam was running youth groups, “all involved in affairs of what was then Palestine.” He was a Zionist in those days, though it was a leftist stream of Zionism, one whose bi-nationalist outlook would be considered anti-Zionist today. (Chomsky then, as now, opposed the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine, believing that it would carve up the territory and marginalize its Arab population.)

The idea of moving to Palestine and joining a kibbutz was becoming more and more alluring—especially since he found himself “very disillusioned” by courses that had looked exciting in the Penn catalogue, but weren’t.

“I was about ready to quit,” he recalls. “That’s when I met Harris.”

That would be the late Dr. Zellig Harris C’20 Gr’34, the Russian-born linguist who founded and chaired the linguistics department at Penn (first in the nation), and whose books included Methods in Structural Linguistics, Mathematical Structures of Language, and Papers in Structural and Transformational Linguistics. Although his family and Chomsky’s knew each other slightly as part of the same Philadelphia Jewish community, it wasn’t until they began to talk at Penn—drawn together not by linguistics but by politics—that the neurological sparks began to fly.

“The primary teacher of Noam was Zellig Harris,” says Dr. Henry Hiz, emeritus professor of linguistics, who also taught Chomsky at Penn. “It’s very difficult to describe the profound influence Harris had on him—and on me, too.”

“Zellig was a primary influence on Noam, perhaps the primary influence back then,” agrees Carol Chomsky CW’51, who went by Carol Schatz until she and Noam were married in 1949. (See sidebar on p. 42.) “Noam admired him enormously, and I think it’s fair to say that Zellig was responsible, in so many different ways, for the direction that Noam’s intellectual life took then and later.”

The relationship between Harris and Chomsky appears to have been a complicated one. The two later parted ways, and while Chomsky downplays that and attributes it mostly to his own growing political activism during the 1960s, he also mentions “Zellig’s lack of interest in my work, which dates back to the late ’40s, when I was an undergraduate”—adding that “it was never of the slightest concern to me—never thought about it twice, in fact; seemed entirely natural, for whatever reason.”

He has acknowledged Harris’s influence on him, both personally and professionally.

“My formal introduction to the field of linguistics was in 1947, when Zellig Harris gave me the proofs of his Methods in Structural Linguistics to read,” noted Chomsky in the 1975 introduction to his own early work, The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory (a chunk of which served as his 1955 Ph.D. dissertation for Harris). “I found it very intriguing and, after some stimulating discussions with Harris, decided to major in linguistics as an undergraduate” at Penn.

Harris, says Chomsky now, “was a very impressive person in many respects, and one of the things that he was very much involved in at the time and attracted me instantly was the socialist, bi-nationalist ideas about then-Palestine. He was a leading figure in a group called Avukah, which was sort of a left-Zionist, anarchist, socialist group of young Jewish intellectuals. The core interest was Palestine, but it was broader than that.

“He never wrote much,” Chomsky adds, “but he was a very powerful personality, and he was very interested in encouraging young people to do things.”

Along with teaching him a “tremendous amount” about political matters, Chomsky recalls, Harris “just kind of suggested that I might want to sit in on some of his courses. I did, and I got excited about that.” So much for dropping out.

“In retrospect, I’m pretty sure he was trying to encourage me to get back in,” says Chomsky. “I started taking, at his suggestion, graduate courses in philosophy and math.”

Those included graduate-level philosophy courses with the late Dr. Nelson Goodman, and graduate-level mathematics with the late Dr. Nathan Fine G’39 Gr’46. He also studied Arabic with Dr. Giorgio Levi Della Vida, whom he has described as an “antifascist exile from Italy who was a marvelous person as well as an outstanding scholar.” And, of course, he took linguistics courses with Harris, though according to Chomsky, they usually didn’t meet in classrooms.

“There used to be a Horn & Hardart’s right past 34th Street on Woodland Avenue,” he recalls, “and we’d often meet in the upstairs, or in his apartment in Princeton. His wife was a mathematician; she was working with Einstein.”

Despite the linguistics courses, most of which were with Harris, Chomsky says he “never studied linguistics in a conventional or formal manner” at Penn. “The fact of the matter is I have no professional training or credentials. I could never get admitted to this department [at MIT]. It’s kind of a well-known fact in the field; it’s not a secret. I had a very idiosyncratic background, and was interested in other things.”

“Chomsky’s education reflected Harris’s interests closely,” writes Randy Harris in The Linguistic Wars. “It involved work in philosophy, logic, and mathematics well beyond the normal training for a linguist. He read more deeply in epistemology, an area where speculation about the great Bloomfieldian taboo, mental structure, is not only legitimate, but inescapable.” The reference is to Leonard Bloomfield, the linguist who dominated the field in the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s, and whose approach is now considered highly methodical, empirical, and behaviorist.

Henry Hiz was a visiting lecturer at Penn in 1951, and among the students in his advanced class in logic and linguistics was Chomsky, then a graduate student. “He was very aggressive,” recalls Hiz; “not only listening but commenting about my lectures. He was very good. And we talked outside my class a lot. I was very impressed.”

Chomsky’s undergraduate honors thesis, which drew somewhat on his father’s work in Hebrew, was titled “Morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew.” He later revised and expanded it for his master’s thesis, completed in 1951. That thesis “set the stage for some of his later work,” writes Barsky, his biographer, and “is taken to be the first example of modern generative grammar.”

That thesis didn’t have much impact at Penn, Chomsky suggests. “As far as I can recall, Henry Hoenigswald was the only faculty member who ever looked at my undergraduate or MA thesis, and no one (to my knowledge) looked at anything I did later.” (Hoenigswald, now emeritus professor of linguistics, says he “didn’t really know [Chomsky] very well,” though he does recall that he was “very brilliant at all times.”)

It was the U.S. Army that prompted him to get his Penn Ph.D., which he “never expected” to receive. In April 1955, having spent most of the past four years pursuing his own edgy interests as a junior Harvard Fellow (for which he was sponsored by Nelson Goodman), he got a draft notice.

“I was 1-A,” Chomsky recalls. “I was going to be drafted right away. I figured I’d try to get myself a six-week deferment until the middle of June, so I applied for a Ph.D. I asked Harris and Goodman, who were still at Penn, if they would mind if I re-registered—I hadn’t been registered at Penn in four years. I just handed in a chapter of what I was working on for a thesis, and they sent me some questions via mail, which I wrote inadequate answers to—that was my exams. I got a six-week deferment, and I got my Ph.D.”

That dissertation, titled “Transformational Analysis,” was actually a 175-page section of a massive work titled The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory, which was so avant-garde that it wouldn’t be published until 1975, and then only in part. “I was writing mostly for myself, because nobody was interested in this long thing,” he says. “It was 500 pages, I guess. My wife and I ran it off on something called a hectograph. I don’t know how it worked, but it turned everything purple. The whole room was purple. We just ran off 20 or 30 copies of this thing for friends.”

The original copy of “Transformational Analysis”—typed in sober black ink and signed by Harris—is still in the Rare Book and Manuscript collection at Van Pelt Library. In his preface, Chomsky wrote that it was “carried out in close collaboration with Zellig Harris, to whom I am indebted for many of the fundamental underlying ideas.” In addition to citing Harris’s Methods in Structural Linguistics and an article in Language, “Transformational Analysis” was also informed by Henry Hiz’s then-unpublished “Positional Algebras and Structural Linguistics.” And in the opening pages, he stated that a linguistic grammar should answer such then-radical questions as: “How can a speaker generate new sentences?”

The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory was “written for Chomskyan linguists when there was only one, Chomsky,” says Randy Harris. Another linguist, H. Allan Gleason, later recalled: “A few linguists found it very difficult; most found it quite impossible. A few thought some of the points were possibly interesting; most simply had no idea as to how it might relate to what they knew as linguistics.” They would, soon enough.

Today, Chomsky says that if his hand had not been forced by the Army, his academic career might have ended. “Because I really had no specific intention of going on in academic work. I was fairly interested in what I was doing, but it wasn’t a field. That’s why I’m at MIT”—which in those days didn’t even have an undergraduate linguistics department.

His appointment was in MIT’s Research Laboratory of Electronics—the perfect spot for Chomsky, who says he didn’t know the difference “between a radio and a toaster.” (He also told the director that the machine-translation project to which he would be assigned had “no intellectual interest and was also pointless”—and got hired anyway.) But his research was open-ended and his appointment only partial, so in order to support his family he had to teach: German, French, philosophy, logic—and linguistics. “He taught hislinguistics,” writes Randy Harris, “and the lecture notes for this course became the answer to the rhetorical gulf between the audience for Logical Structure … and everyone else in the field.”

Those notes were revised and published in 1957 as Syntactic Structures. Once again, Chomsky noted in the preface: “During the entire period of this research I have had the benefit of very frequent and lengthy conversations with Zellig S. Harris. So many of his ideas and suggestions are incorporated into the text below and in the research on which it is based that I will make no attempt to indicate them by special reference.”

Syntactic Structures was “one of the masterpieces of linguistics,” says Randy Harris in The Linguistic Wars. “Lucid, convincing, syntactically daring, the calm voice of reason calling from the edge of a semantic jungle Bloomfield had shooed his followers from, it spoke directly to the imagination and ambition of the entire field.”

Chomsky, whom Harris describes as a “moody Hamlet” occupying center stage during the linguistic “border disputes,” is not terribly impressed by the dramatization of his professional work.

“I never paid attention to the ‘linguistic wars’ fabricated by enthusiastic postmodernists,” he says. “The stories are comical.”

Noam Chimsky couldn’t fathom the nuances of linguistics but Noam Chomsky can.

Semantically, there is a reason for that. Nim Chimsky was a celebrated chimpanzee. A researcher tried to teach him to put together words (using signs) to make sentences that adhered to the rules of grammar. It didn’t work. Chimps don’t have the I-language.

The nuances of linguistics couldn’t be fathomed by Nim Chimsky but can be by Noam Chomsky.

This time, forget the meaning, the semantic significance. The two italicized statements about Nim and Noam are “transformationally” related sentences, meaning that they are syntactic variations with the same meaning.

Transformational grammar was developed not by Chomsky but by Zellig Harris. (Or: Zellig Harris, not Chomsky, developed transformational grammar.) Chomsky later wrote that when he “began to investigate generative syntax more seriously” in the late 1950s, he would “adapt for this purpose a new concept that had been developed by Zellig Harris and some of his students, namely, the concept of ‘grammatical transformation.’” (“Generative” refers to the mental machinery for describing all of the infinite possibilities for sentences with a few “rules.”) For Chomsky, transformational grammar was not an end but a beginning.

“Chomsky is a very original mind, and made out of Harrisian ideas many new ideas, new directions,” points out Henry Hiz. “Harris was not writing about psychological matters; he was writing about formal properties of language. And Chomsky was writing that language was a mental process. And then, that it is the same throughout humanity. Languages therefore are different from each other externally only— internally they are the same.”

For Harris, says Anthony Kroch, transformational grammar was an important tool for analyzing and working with the data. “Chomsky said, ‘Don’t think about the data; think about the knowledge that the person has that allows them to produce the data.’ And that was mentalism—what’s in the minds of people. Psychology at that time was behaviorist, and linguists, to the extent that they thought about psychology, were behaviorist.”

In an epochal 1959 review of B. F. Skinner’s Verbal Behavior in the journal Language, Chomsky demolished the thesis that all language is learned behavior, dismissing as “quite empty” the “claim that all verbal behavior is acquired and maintained in ‘strength’ through reinforcement.” The fact that all normal children quickly acquire “essentially comparable grammars of great complexity,” Chomsky wrote, “suggests that human beings are somehow specially designed to do this, with data-handling or ‘hypothesis-formulating’ ability of unknown character and complexity.”

That was the essence of the Chomskyan revolution. The study of linguistic structure, he added, “may ultimately lead to some significant insights into this matter.” He was right—though as usual, the devil would be in the details.

The brave new world into which Chomsky had led linguistics was an alien one for his former mentor.

“Harris was a behaviorist in his own way, and so for him this was heretical and wrong-headed,” says Kroch. “And it looked like a big step backwards, because behaviorism was a kind of progress over the woolly-headed mentalism of the late-19th century. So from the point of view of 1950s psychology, it looked like Chomsky was saying, ‘I want to go back.’ But of course, it turns out that what Chomsky meant wasn’t a step back but a step forward.”

Penn’s linguistics department, Kroch adds, was “very badly damaged by the falling out between Harris and Chomsky. Not because of anything Chomsky did. But Harris was very angry, apparently, and since he was the kind of person who didn’t like polemics, he shut himself and the department down—in the sense that they sort of hunkered down and waited for the fad to blow over.” That never happened, of course, though Penn’s linguistics department has since recovered nicely.

Around 1980, the efforts of Chomsky and others to show that the “apparent complexity and variety of language was only superficial” crystallized in what is known as the “Principles and Parameters” model. That model postulated “general principles of the language faculty and a finite array of options” or parameters, he says, and it constituted a “major break from a tradition of some 2,500 years.”

Since the early 1980s, Chomsky started every linguistics class with the words: “Let’s see how ‘perfect’ language might be.” That attempt “always led into a maze of problems until about 10 years ago, when things seemed to me to begin to fall together,” he recounts. “That’s what came to be called the ‘minimalist program.’”

All these programs and models about language—sparked by flashes of insight, rigorously tested, vigorously debated—have grudgingly yielded results that resonate far beyond linguistics.

“It is possible that in the study of the mind/brain we are approaching a situation that is comparable with the physical sciences in the seventeenth century,” Chomsky told Randy Harris, “when the great scientific revolution took place that laid the basis for the extraordinary accomplishments of subsequent years and determined much of the course of civilization since.”

Zellig Harris, who retired in 1980, died in 1992. Five years later, Chomsky was the featured speaker at a Penn-sponsored conference that celebrated Harris’s posthumously published book, The Transformation of Capitalist Society, though his remarks focused not on Harris but on the problems caused by capitalism.

“It’s true that I had no contact with Zellig after about 1964,” says Chomsky. “Maybe a letter or two. Remember that by the early 1960s, I was head-over-heels involved in antiwar activities (as well as a host of other activist engagements).” As a result, he “rarely had any contact with people who were not similarly engaged.”

While losing contact with Harris was difficult from a personal point of view, he acknowledges, “it was nothing unusual at the time. Same with just about everyone who wasn’t involved in the activism that was taking over my life.”

When Norman Mailer was arrested for crossing a police line at the 1967 anti-war demonstration in Washington, D.C., he found himself in a jail cell next to Chomsky, who had been nabbed on a similar charge. In The Armies of the Night, Mailer describes him as a “slim sharp-featured man with an ascetic expression, and an air of gentle but absolute moral integrity.” After trying to think up an incisive question or two about linguistics for the “tightly packed conceptual coils of Chomsky’s intellections,” Mailer changed his tack and the two men “chatted mildly of the day, the arrests … and of when they would get out. Chomsky—by all odds a dedicated teacher—seemed uneasy at the thought of missing class on Monday.”

Most of Chomsky’s activism does not involve hobnobbing in jail cells with celebrities. A lot of it is lonely, dogged work: speaking out at churches and universities on U.S. policy in places like Iraq and Indonesia; giving interviews to small magazines and radio stations; and churning out truckloads of articles and books. He is a draw, certainly—one of the very few among political southpaws—but the market for cerebral left-anarchist moral scourges has never been bullish. What drives him is a sense of outrage and responsibility: the “responsibility of intellectuals to speak the truth and to expose lies,” as he wrote back in 1967.

He’s been at this for more than 60 years, having written his first political article—about the Spanish Civil War—when he was 10. “It was about the ominous nature of Barcelona falling after Austria and Czechoslovakia,” he recalls, “and ‘you know what this means.’” He still gets a fond look in his eyes when discussing the Catalonian anarchist movement, which was crushed by communists and fascists. “I was always on the side of the losers,” he once said. (Given that he voted for Ralph Nader in the most recent presidential election, he still is.)

Chomsky’s own anarchist views have deep philosophical roots—though given the misconceptions generated by the word anarchist, he often uses libertarian socialist instead. He cites Adam Smith and Wilhelm von Humboldt as two “founders of modern liberalism” who believed in “what was later called a kind of ‘instinct for freedom.’” From those “fundamental rights” grounded in our nature, “many leading figures of classical liberalism drew very libertarian conclusions, which then fit into the anarchist tradition.” And most of those classical liberals, he maintains, “would be appalled by what’s called classical liberalism today.”

In keeping with that “instinct for freedom,” Chomsky encourages those dissatisfied with the American political system to organize themselves and get involved. “The dominant political philosophy with progressive groups is that people are stupid, ignorant, don’t understand what’s good for them,” he argues. “‘It would be improper to allow them to run their own affairs, so we just have to do that for them.’”

That outlook, he explains, “goes back to James Madison and the constitutional system, which is supposed to be not a democracy but what’s called a polyarchy in the political-science literature—a system in which those who call themselves the ‘responsible men’ or the ‘intelligent minority’ or something, rule. The role of the population is to observe and agree once in a while, to lend their weight to one or another member of the dominant group, and then go home and do something else. The little secret that’s not mentioned is that the ‘responsible men’ become responsible by serving external power.”

In a democracy, Chomsky argues, propaganda plays the same role that violence plays in a dictatorship. Those who control and benefit from the political system preserve it by marginalizing alternative political views (like his); by selectively reporting on the actions and consequences of American foreign policy (virtually ignoring massacres in U.S.-supported Indonesia, for example, while focusing on similar crimes in “enemy” countries like Cambodia); and by creating political apathy among the general population.

That apathy is achieved by all sorts of devious means, ranging from campaign contributions that exclude all but the wealthy to an over-emphasis on sports and other frothy diversions by media conglomerates. Corporate mergers among news organizations, he notes, contribute to the narrow range of views and the general climate of propaganda. And while he has been searing in his criticism of the U.S. government, he is even more concerned about the alternative power structure—the “major corporate system”—now on the ascendant.

“A corporation is about as close to a totalitarian institution as anything humans have devised—unaccountable, secret, hierarchic,” he says. “That’s where the decisions ought to go, according to the prevailing ideology.”

For those who find his worldview more suited to the X-Files, Chomsky would shrug and say that most Western intellectuals can’t allow themselves to even acknowledge the propaganda model, let alone buck the system. His views get a better hearing in Europe and even Israel, despite his withering criticisms of the Israeli government. (In his view, the Israeli press is both more honest and more open to divergent viewpoints than its American counterpart.)

One can—and many people do—disagree with his flagellating approach, but his own moral code is one of almost unbearably high standards. To him, there is little moral value in criticizing the actions of one’s official enemies, even if the criticism is factually correct.

“The moral significance of some human action is determined by its anticipated human consequences,” he says. “That holds true for condemnation as well as any other action. Thus, Soviet commissars and Nazi propagandists bitterly condemned U.S. crimes, quite often accurately. What was the moral value of that condemnation? In fact, it was negative: these were acts of depravity, from a moral point of view.”

“It’s kind of impressive that he has really always criticized his own side of things,” says Anthony Kroch. “He’s Jewish and he criticizes Israel; he’s American and he criticizes the American government. And people get really furious. But it’s not like there’s going to be a mass movement of people who are self-critical. Nationalism is pretty dangerous and murders people by the millions—and yet one guy who is consistently anti-nationalist gets everybody up in a lather.”

At one point during our e-mail exchanges, I ask Chomsky what keeps him engaged.

“I’m often asked that, and never understand,” he replied. “If you see a child being beaten to death in the streets, and try to do something about it, does someone have to ask you why you are engaged? The only sensible question is why I am so little engaged, and why many others choose to be even less engaged.”

The last word goes to Carol Chomsky, who has been involved in her share of political activities over the years—and who, presumably, knows him better than anyone. I ask her if she ever disagrees with her husband about politics.

“Sometimes I do disagree,” she replies. “Mostly I keep quiet about it, because one never wins an argument with Noam.”

SIDEBAR

The Way They Were (and Are)

When Dr. Carol Chomsky CW’51 accompanies her husband on lecture tours, she often finds herself surrounded by “very young and breathless” women, who inevitably ask her the same question: “So what’s it like to be married to Noam Chomsky?’” Her response, which took her some time to work out: “I’ll tell you one thing—it’s never boring!”

A mixed compliment, perhaps, but no small achievement, given that she’s known him since they were children and has been married to him for more than half a century.

Back in the old country—Philadelphia—she was known as Carol Schatz. Her family and Noam’s belonged to the same synagogue.

“His mother was my Hebrew School teacher, and his father was the principal of the Hebrew School,” she says in an e-mail interview. “Later, when I attended the Hebrew Teachers’ College of Philadelphia (Gratz College), his father was one of the professors.”

It’s hardly surprising that it took some time before she became romantically interested in a boy she had known since she was five.

“When we were early teenagers, I viewed him as an overly intellectual, undersized, ‘nerdy’ sort of kid,” she recalls. “In our early teens, he definitely wasn’t somebody I would have wanted to date.”

But by the time she was about 15, she found herself changing her mind. “We were heavily involved in Jewish cultural activities—Zionist youth groups (for Noam it was certainly not the standard ‘Zionist’ viewpoint), Hebrew-speaking groups, Hebrew-speaking summer camps, social activities. He knew more about these things than anyone else, and assumed a position of leadership. So he was very noticeable and admirable.”

They began to date sometime in 1947—the year she began at Penn, and the year that a disillusioned Noam nearly dropped out. Her memories of the University are a little warmer than Noam’s. “I loved it there,” she says. “I found my interests; had many excellent, even wonderful professors; and looking back, received a quite satisfactory intellectual grounding.”

But as for those first, heady years of college romance, well …

“My recollection is that Noam and I didn’t see all that much of each other at Penn, simply because we were so busy,” she says. “We were both working (teaching Hebrew School), and involved in so many things outside of school. Life was compartmentalized. You went to school during the day, did your homework, taught Hebrew School, and pursued the rest of your life in what time remained.”

Somehow, they found the time to get married in 1949, when she was 19 and he had just turned 21. Did she, I wonder, have any idea what she was getting in for?

“I think I did know what I was getting in for, but found it exciting,” she says. “One of his political ‘mentors’ took me aside and explained to me about his politics, the extent of his radicalism, and the dangers his views could come to pose over time. He wanted to make sure I was aware of how extreme Noam’s views were and what that might mean for the future. So I guess you could say I did know, in a general and overall sort of way.”

Two years after she graduated from Penn in 1951, the young couple moved to a kibbutz in the new country of Israel. While Noam was turned off by the “Stalinist” political leanings of the kibbutz, they both had some practical objections, too.

“The setup that we foresaw there would not have been personally acceptable,” she explains. “I would have lived in the kibbutz of our choice, and Noam would have spent the week in the city at a university job, coming home on weekends. This didn’t seem desirable to either of us. I think we never really regretted the decision not to return.” They now live in the Boston suburb of Lexington.

In the 1960s, Noam’s political activities were sufficiently intense that they decided that she should go back to graduate school to earn her doctorate. That way, if he were jailed for any length of time, she could support herself and their children, Aviva, Diane, and Harry. That never happened, though he has seen the inside of a jail. (See main story.)

She got her Ph.D. in linguistics at Harvard, and her work has been in language development and psycholinguistics. But don’t jump to any conclusions. “It’s a very different sort of ‘linguistics’ from Noam’s pursuits,” she says. “I always have to laugh when people talk about how interesting our dinner-table conversation must be since we’re in the same field.”

She taught for many years at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, in the Department of Reading and Language, and became involved in “educational issues of literacy and the like.” She has since “moved into educational technology, and developed software for language and reading.”

I wonder if she has any hopes or dreams of a quiet, disengaged retirement with Noam, now that he is in his seventies and a grandfather of four.

“I’ve given up on that one,” she responds. “He’ll never stop. Actually, it’s probably a good thing for him. So I settle for water sports in the summers, an occasional hour of television during the long, dark winters, and endless discussions of the grandchildren’s latest antics. Not too bad a deal.”