Practicing the craft of TV editing.

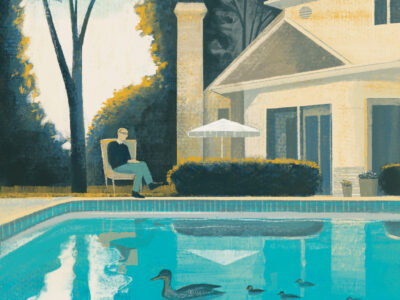

Since few people outside the movie and TV business understand what Kabir Akhtar C’96 does, he’s had to develop some more graspable analogies.

Cooking, for example. Writers craft a recipe; directors and actors gather the ingredients, and it’s the editor’s job to turn it all into a five-star meal.

“People can tell you what a camera operator does, what hair and makeup people do, what writers do,” says Akhtar. “What we do is like the dark arts of film production.”

Lately, he’s been stepping out of the shadows. After 15 years working as a TV editor, he landed an Emmy nomination for Netflix’s 2013 Arrested Development season. Since then, his high-profile projects have included two seasons of New Girl and some Emmy-winning work last year on the pilot of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. (He returned for the third season, which The CW Network unveiled last month.)

When he’s cutting an episode, Akhtar decides which takes were the strongest and which camera angles worked best for a scene. He checks to see whether an actor gave a funny look or delivered a line just right. Then he weaves the best of the best into a single, absorbing story. That zoomed-in view of the happy couple, the crowd shot, the jokes that arrived rapid-fire or the conversation that wound up getting re-dubbed—he’s the one who assembles them into an episode.

Skillful editing can cover up acting mistakes or subpar directing, but a shoddy edit can ruin an entire project, he says. “An audience is not really going to notice bad editing. They’ll just start feeling disconnected from what’s happening, or bored, or have a sense that something’s wrong without knowing why.”

David Novack EAS’86, a documentary filmmaker who teaches image and sound editing at Penn, agrees that if you’re thinking about the editing in a movie or TV show, it means there are major problems with it. “Editing and sound, in their most creative moments, work on the subconscious,” he adds. “They’re kind of unsung heroes that way.”

But Akhtar has always been content behind the scenes, even as an undergrad at Penn. He worked on the tech side of student theater productions with iNtuitons, Arts House, and Stimulus Children’s Theatre. One especially busy week he tallied it all up: he’d spent 70 hours in the theater and about six in the classroom.

When a friend suggested film school, Akhtar initially thought it was “such a dumb idea,” he recalls. “But all of a sudden it all lined up.”

In a sense, the roots of his career run very deep. Born into a long line of artists and poets, Akhtar has numerous relatives working in Bollywood, including an award-winning lyricist uncle, an aunt who’s won multiple acting awards, and two cousins who direct movies.

“Weirdly,” he says, “I’m in the family business”—a genealogy confirmed by headlines from Indian news outlets heralding his 2016 Emmy: “It’s an Emmy for the other Akhtar!” and “Shabana Azmi’s nephew … wins an Emmy Award.”

When he moved to LA in 1998, Akhtar figured he’d get a job as a production assistant (PA) or an editor.

“It was a pretty naïve lack of understanding,” he says. “One of them is a creative lead on a show and you’re working one-on-one with producers and directors and studio heads. And the other is PA-ing.”

His first job was in editing, and he was soon cutting episodes of the late-’90s cable juggernaut Behind the Music. Finally, after more than a decade of projects had filled his IMDB page, Akhtar scored a gig working for Arrested Development.

“Immediately afterward, all the doors flew open,” he says. One led to the pilot for a musical-style series that became Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. When Showtime passed on it, the family-friendly CW snatched it up. To make that transition work, Akhtar re-cut most of the pilot—which landed him an Emmy for Outstanding Single-Camera Picture Editing for a Comedy Series.

“We only shot two or three new scenes,” he says, “but still changed it from an R-rated Showtime pilot to a PG-rated Monday-nights-at-8 p.m.-CW show. That’s the power of editing.”

Since the series weaves original songs, sung by its leads and supporting cast, into each hour-long episode, Akhtar not only had to come up with an editing approach that married screwball comedy with tender moments; he had to do it in a way that made actors breaking into song look natural.

“Finding the balance is a constant challenge,” he says, crediting his years playing bass and singing in choirs with developing his ear. “When do we bring in the song? Should we take out a few bars at the top? How do we turn the corner from this dramatic moment into this comedic moment?”

Aline Brosh McKenna, the show’s co-creator, showrunner, and executive producer, considers Akhtar “one of the founding fathers of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend,” since he helped set its tone and pace from the beginning.

Among the cast and crew, he’s known as “a jukebox of Crazy Ex songs,” according to McKenna, because he knows every number by heart and will pop up with an apropos quote at any moment.

On top of cutting individual episodes, Akhtar is a Crazy Ex producer and the show’s supervising editor. As shooting started for the first season, he went to the real-life West Covina, California—where the series is set—to help find some scene-setting shots. At one location, he spotted a squirrel on the edge of a trash can and started filming. The camera-shy rodent quickly dove back in.

“Instead of turning off the camera, which most people would do, Kabir patiently waited,” McKenna says. “The squirrel emerged with a French fry and sat on the lip of the garbage can and carefully ate the fry. That squirrel interstitial is in a ton of our episodes, and that is a pure, 100-percent-Kabir gag. He has an eye for the unusual, found, quirky joke.”

McKenna and Bloom were so impressed by Akhtar’s skill and taste that they asked him to direct an episode in the second season. It wasn’t his first time in the director’s chair—his résumé includes short-format comedy and segments for 175 Unsolved Mysteries episodes—but he’s already slated to direct two more Crazy Ex episodes in the current season while continuing his editing work on the series.

“Cooking dinner with someone else’s ingredients for such a long time, you get to a point where you’re like, ‘I know exactly what ingredients we need to make a great dinner,’” he says, returning to the culinary analogy.

But he can’t imagine giving up editing entirely. “The goal is to be directing more, but editing is like a crack habit,” he says wryly. “I keep saying I’m going to stop, but I really like doing it.”

—Molly Petrilla C’06