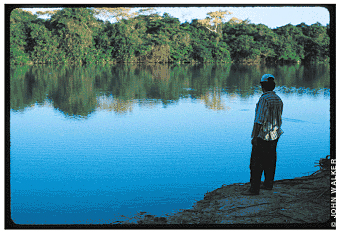

From flood to drought on the Upper Amazon.

By John Walker

The donkey and I have a difference of opinion about crossing the river. To me, the mighty Omi does not look like much of an obstacle, because in the dry season of July it is only about 20 feet wide and less than three feet deep; five months earlier, it was 100 yards across and 60 feet deep. My horsemanship limits me to dismounting and pulling him by the reins. I can’t hope to win a tug-of-war when I am outnumbered in the article of feet—and it would be unwise to encourage from behind, where two of those feet could come into violent action. Muttering, I tie the donkey to a tree and slog through the river toward a neighbor’s ranch.

I was directing an archaeological project in the Bolivian Amazon when the supply of charque, or salt beef, ran out. The owner of the ranch where I was staying was absent, and the employees didn’t have the authority to slaughter. Being the wealthiest person in camp, I was urged to solve this serious problem. We turned on the two-way radio for a consultation with our closest neighbors, some eight miles away. They were sympathetic to our plight, and so this morning I set out on the most tranquil mount available.

I offer money, but the neighbor scorns the concept that he would sell food, and insists that I take back two gunny sacks full of stiff slabs of gray, smelly, heavily salted charque (pronounced char-kee), as well as some fresh meat. He implies that my food-buying errand does not reflect on me, but on my host, who had perhaps neglected proper hospitality. Back at the river, there is no trace of shame on the face of the donkey, only perhaps a fleeting expression of curiosity or amusement, as I get my pants wet again. But he is steady (if slow), and two hours later we are home. I have lost a day of work, but the dynamic landscape I am studying doesn’t always respect my plans, or my preconceptions.

To the degree that it has fame, this country is known for mountain scenery. Bolivia’s capital is more than two miles high. Trekkers and climbers stream through La Paz on their way to Lake Titicaca and Cusco every year, but only recently have they begun to talk about the eastern lowlands. On the other hand, everyone has heard of the Amazon, where jaguars scream, anacondas lurk, and trees soar overhead like the pillars of a cathedral. Somehow, in isolated corners of this untouched wilderness, humans have survived by maintaining their connections to this unique ecosystem.

These romantic images fall short of the truth. Bolivia is more than mountains, and the Amazon and its history are more than forest. Only 10 million people live here, but in area Bolivia equals Texas plus California. Almost half of the country is a low plain that eventually drains to the Amazon, but this is not all forested. Much of it is a prairie called the Llanos de Mojos, which is contained within a state or departamento called the Beni. This huge area revolves between the arid month of August, and the floods of February and March. There are forests, but they are usually confined to high ground and the riverbanks.

Today, Benianos pursue the steady occupation of cattle ranching, but their economic history is a series of booms and busts: rubber, alligator hides, cocaine. Prosperity has never come to stay, only to visit. Political history is a series of footnotes: the Jesuits and the Portuguese, military advisors and Ché Guevara. But there is a vibrant economy that doesn’t depend on money, as well as an active political scene. (The latter is marked by steak-and-beer rallies and campaign theme songs broadcast by loudspeaker-carrying pickup trucks that start their rounds before dawn.) Even people who have reliable incomes know other ways to produce wealth.

In the town of Santa Ana, the family I live with does a brisk business in their front room, a pool hall. The first players arrive around 8 a.m., and the last leave after midnight. They only pay one boliviano (about 15 cents) for a game, but this provides a steady revenue stream. Nevertheless, one always looks for chances to buy low and sell high. To finance the expansion of the house into a hotel, my friend decided to sell his most valuable firearm, a pearl-handled revolver. He soon had a good offer of 12 yearling cows. After they were fattened on land near town for a few weeks, the cattle fetched a grand total of $1,200, about as much as billiards makes in three months. Today, the walls and the roof of six rooms are in place, including the room that we are going to use to start our regional archaeology museum.

The people of the Beni, and the abandoned fields and broken pottery that we use to study the prehispanic past, provide the material for anthropological study. It’s less clear what anthropologists provide them in return. Images of the people living along the Amazon, like Rousseau’s concept of the “noble savage,” have influenced western thought for hundreds of years. But satellite television, Internet cafes, and pirate DVDs show that ideas are moving in every direction. Many Benianos have moved to Italy and Spain in search of better jobs. When they return, they bring gifts like VCRs and espresso makers—as well as tales of the exotic lands beyond the curiche grande, or “the big swamp,” as the Atlantic is sometimes called. It used to be difficult to find a telephone in town, but this year my friends have a cell phone in the house. They are not waiting for landlines to be built in order to take advantage of the flood of information that modern technologies bring.

I am not a fisherman, but in the wet season, when we are not able to excavate, even I can be useful on a fishing trip. Piranha (or palometa) are only four to eight inches long but they have a mouthful of sharp teeth. Many groups of indigenous people use palometa mandibles to carve wood and cut other materials. When the fish get excited, you can catch one by throwing in a hook with a piece of red cloth on it, or even with no bait at all.

I have a visible reminder of my own tastiness earned while catching palometa from a lakeside. After flipping one onto the beach, I stepped on it with my rubber boot to keep it in one place. As I reached for my knife, my foot came up, and the fish flipped towards the water. Without thinking, I reached back with my off hand. Suddenly I felt a stinging, electric pain. The palometa had made a deep wound in the fourth finger of my left hand, almost gulping down a piece as big as a half-teaspoon. The large first- aid kit I had carried with me all over creation finally came into its own, and I kept all of my finger. But the scar is most gratifying, and I always think kindly of that fish as I crunch down its cousins, either grilled (with lemon and salt) or boiled (tomatoes and onions are good).

Using a canoe improves the catch, but you might need more equipment. Fishing in February you lose hooks in the trees below you. In July you can find them again, by reaching high above your head to pull them out of the branches. Each time I return to the Beni, I adjust to where the water has moved to now.

John Walker Gr’99 is a research associate at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. His first book Agricultural Change in the Bolivian Amazon(University of Pittsburgh) will be published this fall in Spanish and English (www.sas.upenn.edu/~jwalker).