Class of ’87 | Michael Tiemann EAS’87 is a dreamer, but a practical one. If you ask why he sank several million dollars of his own money into building Manifold Recording—a lavish, state-of-the-art studio in rural North Carolina—he has a ready answer.

“There are so many artists whose music I love, but I hate their records,” Tiemann says with a laugh. “So this represents an opportunity to step in and try to come up with a different or better way to make something better that’s not been done to my liking.”

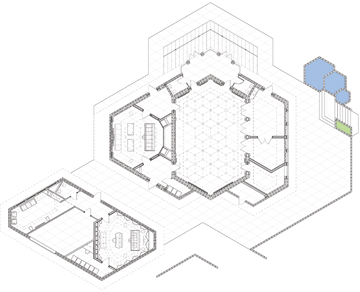

Manifold looks as amazing as it sounds—a geometrist’s dream, with the golden ratio, the Fibonacci sequence, and other mathematical constructs coming into play. All the grids created by shapes and angles on the floors, walls, and ceilings line up and interlock with perfect symmetry. The studio’s wooden floor has a diamond pattern, and each diamond consists of 12 slats to symbolize the 12-note scale of Western music.

“When you meet Michael, you instantly realize that he’s serious,” says Wes Lachot, whom Tiemann commissioned to design Manifold. “He’s fun, very brilliant, and it’s clear he’s not fooling around. He was ready and willing to do something radical, which I liked the sound of. So I took some chances on the design that I would not have taken with the average client. It was a fairly radical step forward. But Michael was the right kind of client, with the stomach and creativity for it. He’s interested in giant leaps forward.”

Tiemann has always had a visionary streak, going back to the early days of the Internet and his work with open-source software. As his most ambitious project yet, Manifold is a way for him to combine various passions. Tiemann has been interested in music and recording since childhood, when he sang in New York’s famed Saint Thomas Choir at age 10. And his open-source mindset gives him a unique perspective on the music industry.

“I wanted to build something like 30th Street Studio in New York City, which was the crucible of the jazz scene up there,” Tiemann says. “Miles Davis used to bring in a few dozen people to have audiences for live recording sessions there, and 30th Street is where Glenn Gould recorded the famous ‘Goldberg Variations.’ Gould also wrote ‘The Prospects of Recording,’ and said that recording would someday completely replace live performance. That was in 1966, and it hasn’t happened yet. But I want this studio to be something that’s a hybrid of recording and performance.”

Before plunging into the studio business, Tiemann made his mark in the high-tech field. He came to Penn as a business major and quickly realized that Wharton wasn’t for him, whereupon he switched to the School of Engineering and Applied Science, focusing on computers and software. After graduation, Tiemann went to work for Modular Computer Company in Texas “with a plan to change the world through computers,” and it kind of worked out that way.

It was the late 1980s, and the Internet was just beginning to take shape. Tiemann was doing a lot of work with open-source software—free software designed to be easily modified by other users. In Tiemann’s experience, open-source software was “magic,” far superior to the proprietary equivalents on the market. But it wasn’t clear how one could make money from open-source software until Tiemann hit on the idea of giving it away and selling support services. While that seems obvious now, it was a radical notion at the time.

“I knew this free software was magnitudes better than anything else,” Tiemann says. “But the idea of building value by giving it away, nobody had figured out how to make that work, not even me—until I realized, ‘Nobody thinks this will work, so there’s no competition.’ The freedom of no competition made me feel like there was no way we could fail.”

Thus was born Cygnus Support, which took on the motto: “Making free software affordable.” Unlike most startups, Cygnus caught on immediately and was profitable from the start; its annual revenues nearly doubled in each of its first five years. By its fourth year, 1993, it had enough cachet to make Fortune magazine’s list of “25 Cool Companies.”

“Cygnus was one of those rare early open-source companies that was completely bootstrap,” says Danese Cooper, who is now chief technical officer of the Wikipedia Foundation. “They had no angel funding, just pulled it together, and they turned out to be one of the few really successful entrepreneurial open-source companies.”

By the mid-’90s, a North Carolina company called Red Hat was making waves with Linux software. Tiemann wanted to buy Red Hat, but he couldn’t talk his Cygnus partners into it. Five years later, the tables were turned and Red Hat had become big enough that it bought Cygnus. But Tiemann took it well, relocating from the San Francisco Bay Area to North Carolina. He also began appearing at open-source conferences wearing a red fedora in honor of his new employer.

“Michael was a really polished guy and he always wore a suit at the conferences, which made him a complete weirdo,” says Cooper with a laugh. “But because he cleans up well, he plays nicely to business. The open-source world is full of people who look kind of crazy, like you should be afraid of them. Michael was the guy who looked like somebody you hoped your daughter would date.”

After the merger, Tiemann became Red Hat’s chief technical officer, and both he and the company thrived as Red Hat ascended, joining the S&P 500 in 2009. Tiemann is now the company’s vice president of open-source affairs, and serves on various boards, including the Open Source Initiative Board alongside Cooper. In both capacities, he is one of the most avid and visible proponents of open-source software.

Red Hat was what brought Tiemann to North Carolina, where real estate was affordable enough for him to build the studio of his dreams—despite the fact that the recording industry has been in a decade-long downward spiral, music sales have plummeted, and high-priced studios have been closing at an alarming rate. Since any room with a laptop computer can pass for a studio nowadays, it seems like exactly the wrong time to build a palatial recording facility that costs $2,000 a day to rent.

But Tiemann envisions more than just a studio for major-label projects. With its large recording room, it can accommodate scores of people interested in watching live recording sessions—which will eventually be broadcast, if all goes according to plan. For Tiemann, who envisions a North Carolina equivalent of Austin City Limits, the seeming impracticality isn’t much different from, say, open-source software.

“People said the idea of giving away software and selling services to new markets would never work,” he says. “That worked out fine and this can, too. What would it be worth to provide a path to sustainable success in the music industry? And what would it be worth to make North Carolina the new place on the map for building a viable and sustainable artistic community? I think that’s worth a lot. The conventional music business is no longer able to fund talent development or the sort of recording that it did 20 years ago. But in that tragedy is an opportunity.”

—David Menconi