Orwell says that at 50 a man has the face he deserves. And at 92?

By Nick Lyons

It’s not an unpleasant face, not to me. The flesh is furrowed, freckled, and the eyes squint. Decades have passed since the hair turned partly gray, mostly white, the beard likewise. There’s a keratosis in the middle of the forehead, black, the size of a half dollar. Now and again someone asks, “Is Ash Wednesday early this year?”

Others have wondered if I’m Indian or if the mark has some religious meaning, a cult perhaps. But it’s just there—only a skin blemish, not the melanoma that took my oldest son. It’s less potent than a basal-cell carcinoma, but more visible.

Orwell says that at 50 a man has the face he deserves. And at 92? Keratosis included?

It’s an old face and lived in, but not as profoundly worn and wise as a Rembrandt self-portrait, beseiged by pain and the knowledge pain often brings, and the mark great art sometimes leaves on its maker, and the losses age cannot forget.

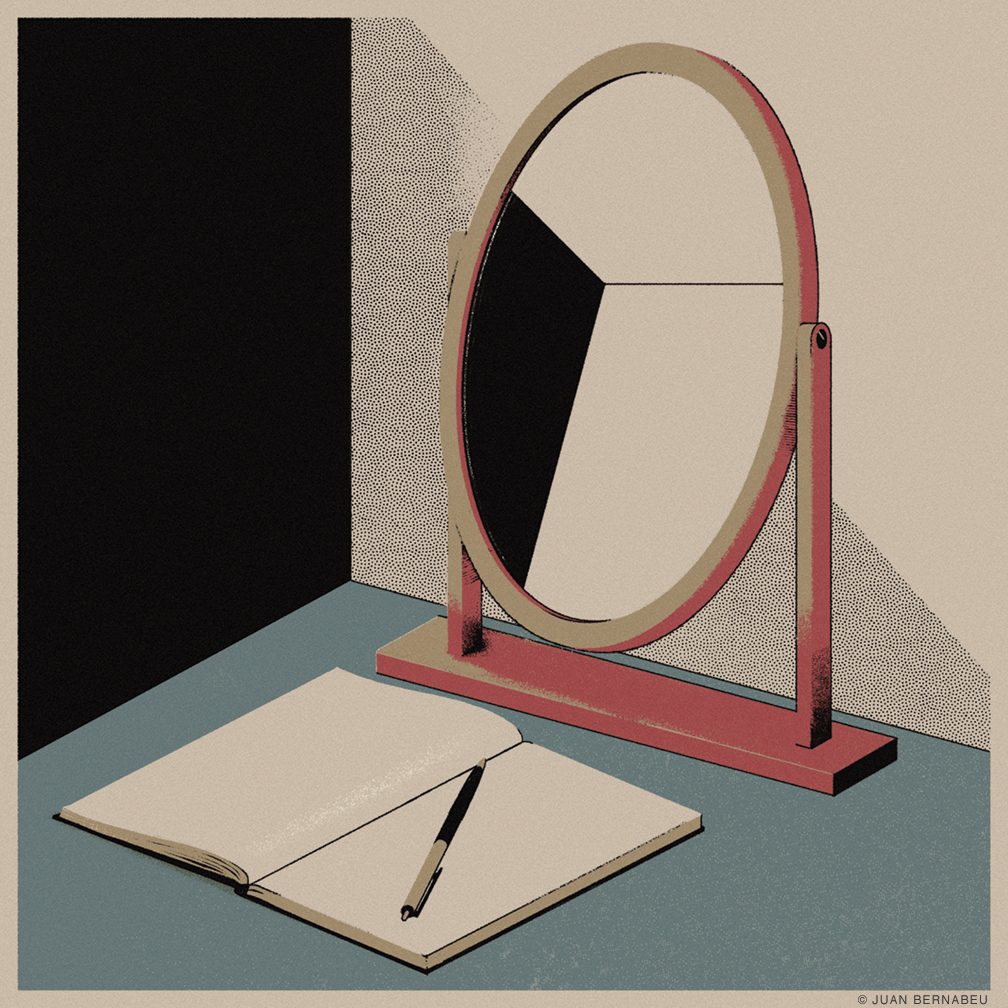

There is nothing there of Dorian Gray’s portrait—that monstrous painted home to his every nasty sin. But my portrait in the mirror says something, or is trying to do so, and I sneak a look at it now and then, to see if it’s in a mood for revelation.

The eyes know more. They have definitely changed. Despite the squint they register some serious stuff and a touch of whimsy, and surely worlds they never knew when I was younger. They may not yet see a world in a grain of sand, and may never do so, but they know the difference between sand in an oyster and in an eye.

At the edges of sleep, when I first lie down and before I rise, my head often fills with images, scenes, remnants of events past—and words, so many words, words that want to be fashioned into phrases and sentences, words that want me to convert them into gold, like Rumpelstiltskin his straw. Much of this I forget but sometimes not. Does this transient dreaming appear on my face?

In those tense years when I only vaguely dreamed of transforming myself, when I found neither hope nor skill within myself, I often had a tired, bewildered look. I could hardly shape words, and never lingered with them. Friends wondered if I had wandered off the rails. One frank teacher advised me that saints with powers of levitation could not rise from the pit I’d dug.

I feel no compulsion to boast how I climbed out, how so many flaws and failings vanished and how something in me sparked and grew into whatever it has now been for decades, something self-sustaining, quietly stubborn, even proud of itself.

Friends my age, even younger, have finished their journey; one told me several times, “Nick, all I want is the ticket out of here.” Quietly, I don’t share that solution. Still, age has brought challenges: Sunday follows Sunday too quickly; my back pains erupt too soon after I begin to walk; reading a book takes hours longer; I need minutes to untangle even moderately complex thoughts, and most road signs take seconds to understand, seconds too long, so I’ve quit wheels.

Except for the black spot on my forehead, I sport few enough marks or scars of age. I don’t dwell on old grievances, false hopes, a multitude of regrets, painful losses. I write a lot and have cheated memory loss by writing very short essays. I can get my arms around these, see them whole, then fuss with them until they sound unfussed-with.

I keep wanting to write better. I like to hear good comments about what I write but I’ve grown such gnarled alligator skin that even a snotty or dead-wrong review might sting for 30 seconds but mostly only draws a smile. The writing is what counts lately, not what happens to it; making it keeps me on this side of senility.

My eyes wake fully when I see Ruth or any of my children, or one of my grandchildren. And I may have fewer friends now, but those left, and a few new ones, brighten my eyes. My best passions are still intact. My worst have mostly slipped downstream.

Today I’ve spent half an hour looking at the face. I don’t rate this narcissistic; I look at myself and write about myself because I worked so hard to save this person and know him better than all else. Something in the writing itself has a voice that is kin to my face—the swift craftiness of basketball, several thousand books, my improbable midlife shape shift, my wild and passionate love of literature, the satisfaction of having shared much with classes, a few years of ghostwriting in other voices, editing the work of hundreds of others, some raw experimenting, fathering, loving deeply and unconditionally, a smorgasbord of disparate occasions, even fly fishing.

My late wife often said that she loved self-portraits because she never had to flatter the model; I don’t want to cheat it.

“Peel your own image from the mirror,” writes Derek Walcott. “Sit. Feast on your life.” At 92 I try to live faithfully with who I now am. I dream of what the face might become—whatever the threats, the unfathomable future. In another five years, perhaps six or seven, how and how much will my image in the mirror change?

Nick Lyons W’53 is a longtime Gazette contributor.

An honest, profound piece of writing. And what a legacy–his talented family includes other accomplished writers, publishers, and literary agents and Nick’s wife, a wonderful painter who left some gorgeous work behind. May we all be that thoughtful about seeing what our face reflects at 92!

Great writing by my friend and classmate Charles Lyons’ father whom I new as a child.