The curator of a show of Roman glass now at the University Museum tells how the ancient glassworking industry reveals as much about the Romans as their architecture, thirst for conquest, or tendency to murder their emperors.

By Stuart Flemming

I was born and raised in South Wales. My brother and I often would spend weekend afternoons clambering over the remains of Roman camps as my father, an amateur artist, captured the charm of nearby villages in and around the Wye valley. I loved reading tales of how the woad-painteThe curator of a show of Roman glass now at the University Museum tells how the ancient glassworking industry reveals as much about the Romans as their architecture, thirst for conquest, or tendency to murder their emperors.d native people, the Silures, fiercely defended their — and my — homeland, holding at bay the better- armed Roman legions (though I also spent hours copying drawings of those Roman soldiers in their fighting gear, standing stoically beneath their eagle-headed standard).

It is Roman militarism, and a centuries-long tendency to solve political problems by murder rather than manipulation (thus, Caligula was stabbed to death by one of his Praetorian guard, and Claudius was poisoned by his fourth wife, Agrippina), that today most strongly color the popular image of the ancient Romans. Remnants of forts, city walls, and roads throughout the Mediterranean cannot fail to impress on any traveler how far afield war and political ambitions took the Romans over the centuries: Westward to Hadrian’s Wall in northern Britain, a place where you can be chilled to the bone by the wind even at the height of an English summer; Northward deep into the dark and mist-enshrouded German forests; Eastward across the baking heat of the Syrian Desert to the banks of the Euphrates river; and Southward to the deserts beyond the Atlas Mountains of North Africa and along the fertile course of Egypt’s Nile.

But there is another side of the Romans that we tend to overlook — their flair for good business. If ancient accounts are true to life, the streets of Rome itself hummed with activity in a way only matched today by the garment district of New York or the noisiest bazaars of Beirut. In Roman society, you were what you owned, so almost everyone was looking for some commercial opportunity that would improve their lot. During the late first century B.C., the industrialization of the glassworking craft offered just such an opportunity — a near-ideal one because, in modern parlance, the R&D had already been done for them, in the Hellenistic world of the eastern Mediterranean.

It has been fascinating for me, after a 30-year career that has mixed radiation physics and archaeology, to create the exhibition Roman Glass: Reflections on Cultural Changeand take a fresh look at the Romans via an aspect of their material culture rather than revive my youthful memories of their militancy. The exhibition, which opened this past September and continues through November at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, includes more than 200 glass vessels — bottles, bowls, cups, and jugs — dating from the late second century B.C. to the early seventh century A.D. and all drawn from the Museum’s Hellenistic and Roman collections. Most have never been displayed publicly before.

Back in 1991, as I began my research into the Museum’s Roman glass collections, I was struck by how certain shapes and decorative motifs cropped up all over the Roman World. This was my first inkling that I was dealing with the products of a full-blown industry, not a minor craft. I knew then that, in part, the exhibition would be a social study of the Roman middle classes and the poor in a way that would carry me far from many of the conventional textbooks on Roman lifestyles.

Meanwhile, I felt that strange tingling sensation on the back of the neck that all of us get when something tantalizing refuses to quite come into focus — in this instance, the fact that the Romans simply did not have a word for glass before about 60 B.C. Yet, through war and trade, they were in full contact with the Hellenistic World, where glassworking was flourishing as never before. I realized I could not move forward with any plan to explain Roman glassworking to the public without first jumping back a few decades in antiquity. Here is what I learned.

SOMETIME AROUND 70 B.C., in Jerusalem, someone realized that, if you took a glass tube — then the stock for mass production of beads — sealed one end and blew into the other, you could create a glass bulb. Blow hard enough and long enough, and you could make a small bottle. This was glassblowing at its most primitive. It is quite possible that, without further refinement, this moment of experimentation might have passed unnoticed. A couple of decades later, however, the introduction of a separate blowpipe, together with a tool-kit of variously-sized pincers and paddles, made it possible to blow and shape glass with much greater control, and with much greater novelty.

But the potential of a technological idea will only come to fruition if its seed is planted in an encouraging cultural environment. During Rome’s Republican Era, in the dictatorial times of Sulla and Julius Caesar, such encouragement seems to have been lacking. In the Hellenistic world, the firmly established traditions of working glass — either by blending threads of it into closed vessel forms or by slumping glass over a pre-shaped model for open ones — were producing fine wares with which the infant technique of free-blowing could not yet compete. In the Roman world, however, pottery was still the material of choice for everything domestic, from fish platters to perfume bottles, and no one seemed to be in any hurry to change that situation.

Enter the Emperor Augustus. It is said that he had no love of foreigners; he viewed the appreciable numbers of them living in Rome around 10 B.C. as a potential source for the corruption of traditional Roman values. If I interpret his subsequent actions correctly, he wanted the Italian mainland to be far more self-sufficient wherever possible. So it was that Italian businesses in certain crafts — most obviously, pottery- and cloth-making — were encouraged to expand. The craft of glassworking now was adopted from the Hellenistic world with much energy and skill. An ancient Industrial Revolution was underway.

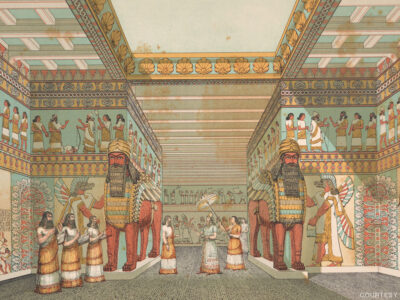

To get things moving, the Romans simply enslaved hundreds of skilled craftsmen in the eastern provinces, uprooting them from their homes and resettling them in the outskirts of rapidly-growing Roman cities. Pottery-makers were imported from Asia Minor, particularly from around Pergamum, and put to work at Arretium; Greek craftsmen were moved from Athens to Lyons and other cities in central Gaul; glassworkers were brought in from the provinces of Syria, Judaea, and Aegyptus — most likely from the cities of Sidon, Jerusalem, and Alexandria — and put to work in shops at Naples, Aquileia, and just outside Rome itself.

There was an immediate market niche for glassware in Augustan times. Like many ancient peoples, the Romans believed in an afterlife that was an idealized form of their worldly experience. According to its means, the family of each dead Roman was obliged to provide furnishings for the grave. Such furnishings always included regular domestic items — plates of food, flasks of wine, and so on — but it was also a tradition to include offerings of perfume. The Roman wealthy would put these offerings in bottles (unguentaria) made of silver or alabaster. The eastern craftsmen who brought with them the skill of glassblowing now offered the rest of the population an alternative in glass; to be sure, not something as elegant or colorful as might have been wished, but which everyone could afford. The free-blown unguentarium was one of the immediate and long-term successes of the newly emerging industry. Modern excavations have revealed many instances where a grave contains not just one or two but a couple of dozen of these, all mass-produced, each in a matter of minutes at most.

At the same time, glass captured the popular imagination by virtue of its translucency. You could see the color of wine in a beaker, or how well a bottle was filled even if it was sealed — which could not be said for items made of pottery, or indeed of bronze, silver, or gold. The production of wine glasses soared in the Augustan era, actually causing the demise of some of the pottery workshops that specialized in traditional beaker types. It was glass’s distinctive property of transparency that stimulated the Emperor Nero’s tutor, Lucius Seneca to observe that “ … Apples seem more beautiful if they are floating in a glass.” (Investigations in Natural ScienceI.6). And, from the middle of the first century A.D. onward, squared-sided glass bottles — typically with capacities in the half- to one-liter range — were used for a great deal of the short-range movement of liquids such as olive oil and the popular fish sauce known as garum.

Thus the industrialization of glassworking in the Augustan era came about through the influence of three distinct forces: First, by virtue of certain historical events (Augustus’s rise to power and his promotion of craft-centralization on the Italian mainland); second, because of a technical innovation (the invention of glassblowing in one of Rome’s eastern provinces); and third, the social pressure related to fashion or taste (a traditional link between perfumery and Roman funerary ritual). Change in the Roman glassworking industry was always most dramatic whenever all three of these forces came together at one time.

I USE THE WORD industry to characterize Roman glassworking almost from its inception with due caution, mindful of the fact that it now conjures up an image of the relentless grinding of machinery and the turning-out of countless identical widgets. Roman glassworking was never as mechanical as that. Yet the scale of production does have a distinctly modern ring to it, as to some extent does the uniformity of its products. Let me move crabwise towards a quantitative view of this point by moving forward the ancient clock to the later Roman era and describing the new direction that Roman glassworking took in the eastern Mediterranean during the mid-fourth century A.D.

In A.D. 326, following a major political rift with the Senate in Rome, the Emperor Constantine moved the administrative heart of the Empire to the site of ancient Byzantium, and named his new city Constantinople. That move, as an historical event, was in itself sufficient to strongly influence the course of glassworking, simply by revitalizing the economies of the neighboring eastern provinces. But Constantine did far more than that. He specifically granted exemption from public service to many kinds of craftsmen, glassworkers among them, so that “ … they might become more skilled in their craft and see to the training of their sons” (The Theodosian Code XIII.4).

What an enlightened decision that was! No sooner was Constantinople dedicated in A.D. 330 than the process began of filling it with fine basilicas. By the middle of the fifth century A.D., there were at least 14 of them, all mixed in with 11 massive palaces of emperors and empresses. Most revered of all amid this new architecture was the Church of Holy Wisdom. Constantine’s version of it was destroyed during riots in A.D. 532. But it was rebuilt and reconsecrated just five years later, its newfound magnificence prompting the Emperor Justinian to declare, “Solomon, I have surpassed you!”

The aggressive imperial building campaign of the fourth century A.D. was sufficient to bring the force of wealth into play with some intensity. As the Roman nobility rushed to gain favor with Constantine’s successors, they donated huge sums towards the construction of more massive basilicas in other cities, including Jerusalem and Rome. Provincial goverment officials, not to be outdone by their urban counterparts and for much the same political reasons, followed suit in towns and villages throughout the Roman world.

As for technical innovation, that came in the form of the cone-shaped lamp. This had become part of the Roman glassworker’s repertoire sometime late in the third century A.D., the earliest of them being made of common green glass and probably used simply to light up domestic storage areas. The practical demands of the ecclesiastical building spree of the fourth century A.D. now encouraged the mass production of such lamps in colorless glass. We can get some sense of the scale of lamp production from an engraving of the inside of the Church of Holy Wisdom that was made by Giovanni Fossati late in the 18th century. All of the white “specks” that he rendered so carefully along the limbs of the eight-sided candelabra are individual glass lamps — close to a thousand of them, if I’m not mistaken, just to illuminate this one church alone.

I would not want this talk of emperors, be it either of Augustus or Constantine, to create a false image of glass’s place in Roman society. There was a quite strict hierarchy in Roman material. If you were in the imperial or senatorial league of wealth, you would eat everything — even your hard-boiled eggs — off only gold or silver; on the next rung down, among the more successful of merchants and government officials, your tableware usually would be made of bronze. For most everyone else, your dishes, water jugs, and wine cups were of pottery or glass. The same material distinction would be made for most domestic items, whatever their purpose.

A typical middle-class Roman household therefore would have glassware scattered throughout its rooms, from the dressing area where, each morning, the lady of the house would have her hair styled and her make-up applied by a personal maid, to the kitchen that came to life late in the day during the preparation of the evening meal. In a remote part of the house there would be an all-purpose room for the storage of farm produce and preserved foodstuffs such as grain and salted fish, and somewhere else there would be a cache of globular flasks that contained massage oils for use in the local public baths. In some instances, there wouldn’t be just one unguentarium or one pickling jar but several of them, each of different size and/or purpose. Conservatively, there were probably about 80 items of glassware used on a daily basis in any sizable rural household and perhaps half that number in any cramped city apartment.

As I drew these ideas together, my physicist’s instincts urged me one step further. How many rural households and city apartments were there, Empire-wide? There will always be debates about such matters, but the consensus view at present is that, around A.D. 116, Rome’s subjects numbered close to 54 million. Perhaps as many as a third of them were slaves, and so not owners of property. That still left a free-born citizenry, however, that probably owned or rented about six million homes. If we allow that just three vessels were broken every year, then glassworkers were turning out a staggering 18 million items of glassware every year — production on an industrial scale indeed.

Every time I make that calculation, I check to be sure I’ve not added a couple of extra zeros; but no, 18 million it is. Small wonder then, that by the middle of the first century A.D. the Latin phrase vitrea fracti had taken on the proverbial meaning of rubbish. A comment attributed to the Augustan geographer Strabo, that “ … a glass drinking cup could be bought for a copper coin” (Geography XVI.2) also indicates that, although a kitchen slave might suffer a whipping for his or her carelessness, the buying of new glassware was not going to strain the household budget much.

If so much glass was being made every year, where is it all now? From modern excavations in urban areas and at the sites of Roman military camps, we know that a lot of it finished up as trash that would then have been crushed and churned over during later construction work. Probably just as much trashed glass was recycled, however — gathered up and bought for pennies to peddlers who then sold it by the sack-load to local glass workshops where it could be re-melted and re-shaped. In fact, broken and discarded glass — what we call cullet today — may have been the only stock available for glassworkers in the more distant provinces, since the importation of pre-made ingots or the raw ingredients for glassmaking from scratch would have been prohibitively expensive for them.

AN INDUSTRY THOUGH Roman glassworking certainly was, it was one that maintained a remarkable degree of dynamism over the centuries. The shape and decoration of two of its main products — the unguentarium and the wine beaker — were being modified every few decades, sometimes quite sharply, and there were many new items of glassware introduced that expanded the glassworker’s repertoire in significant ways. I believe that every one of these modifications or innovations was a response to some shift in Roman taste, and probably a match to one that was occurring among contemporary vessels in silver or bronze.

The way that the Romans committed themselves so heavily to the maintenance of good ports all around the Mediterranean coastline and of fine roads that criss-crossed the entire Empire on land was also critical for keeping the Roman glassmaking industry so dynamic. Of course, the main purpose of such maintenance was to assure the easy movement of troops from one trouble spot to another, and of administrative information from one city to another. But these ports and roads also allowed the movement of people and their ideas. Signatures and inscriptions in Greek indicate clearly enough that eastern Mediterranean craftsmen settled at various places in northern Italy and central Gaul; that north African and Syrian soldiers were conscripted to serve in the army in northern England, thereafter to settle there as tradesmen; and that businessmen of every background and philosophical persuasion traded wherever it was to their advantage to do so. Thus, every Roman city became a social melting-pot where technical innovations could be passed on, blending with or displacing old ideas, sometimes in the space of just a decade or two. The industrial activities of the Roman world responded accordingly, with a freshness of purpose and an ongoing rise in skill.

In the end, when I talk of glass reflecting the Roman culture, I really mean that it reflects the way the people behaved towards one another; people of all walks-of-life — tradesmen with clients, mistresses with maids, businessmen with slaves, and emperors with generals.

One day, two thousand years from now, another scholar will interpret our material culture in the same way as I have treated that of the Roman world here, and recognize within our domestic items an inevitable mirror of ourselves — in that instance, a reflection of our cultural changes to come.

Dr. Stuart Fleming is scientific director of the Museum Applied Science Center for Archaeology (MASCA). This article is adapted from his introductory lecture for the exhibition, “Roman Glass: Reflections on Cultural Change,” given for the membership of the University of Pennsylvania Museum last September.