In a church where victims were massacred, a team from Penn is helping Rwandan officials develop a plan to conserve the material evidence—bullet-riddled walls, blood-stained clothing—that bears witness to the country’s genocide.

BY JOANN GRECO

Photography by Randall Mason

Portrait by Candace diCarlo

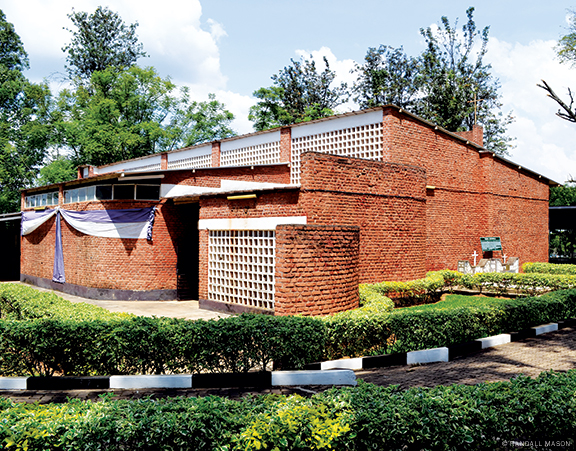

The church at Nyamata, a small market town about 20 miles south of the Rwandan capital of Kigali, is a striking example of African vernacular architecture that would catch the eye of any visitor. Designed by Swiss architect Bernard Jobin in 1980, it expertly blends Western and African stylistic influences in a low-slung structure made of local brick. Traditional Roman arches meld with modernist design touches, then interplay with the concrete grilles that serve as the building’s only ventilation. Inside, the hallmarks of the built iconography of Catholicism await—a baptismal font, a tiny sacristry, an altar. The pews, though, are rough-hewn, just wood boards on brackets. In homage to Notre Dame du Haut—an iconic creation by fellow Swiss Le Corbusier—a clerestory slit wraps the interior perimeter, allowing light to stream in. That gentle glow enhances the quietude, which is only broken by the intermittent chatter of birds high in the trees or the gleeful shouts of children from a nearby school.

Gradually, the visitor notices that the sun’s rays also filter in from the holes that pockmark the roof, left by countless rounds of bullets. And, again and again, the visitor spots the reappearance of the warmth of that red brick exterior—it’s there, in the blood that still stains the walls, and it’s everywhere, in the brick dust that has settled, like a film of memory, on the clothes.

The clothes. “I haven’t seen anyone who hasn’t stopped in their tracks when they enter and see the room just completely stuffed with clothes, all tangled together and strewn haphazardly,” says Laura Lacombe GFA’13, an architectural conservator with Harvard University’s Peabody Museum who is working at the site as part of a team assembled by Penn Praxis, a nonprofit that extends the research and educational mission of the School of Design by creating projects in which faculty and students from different disciplines can collaborate. “They almost look like they could be bodies.”

More so than the skulls and femurs neatly lined up in a downstairs crypt, she adds, the clothes “give you an idea of the scale. There’s a sense of individual loss.”

Gathered en masse, the 35 or so cubic meters of clothing would just about fill a standard shipping container. They lie on pews, lean against walls, slump on floors. People like Martin Muhoza placed them there, plucking them from the bodies of the 10,000 Rwandans who were killed at the site. In April 1994, Muhoza and his family came to the church for refuge from a massacre that marked the start of one of the worst genocides in history.

Most of the teenager’s family was killed; he was wounded and managed to leave the country. When he returned to his hometown months later, Muhoza, like many others, was drawn back to the church. He began volunteering to sift through the carnage, separating human remains for later burial in mass graves, then stuffing pots and pans, wallets, and rosaries into plastic bags, then piling up the clothing. As he and the others worked, day in and day out, they may not have realized that they were readying the site to serve as a memorial to the dead—and a holy reminder of the horrors of genocide to a world that never seems to get the lesson. So it’s fitting that Muhoza, now a grown man with a biology degree, oversees a small staff at the National Commission for the Fight Against Genocide (the acronym reads CNLG for Commission Nationale de Lutte contre le Génocide) charged with the stewardship of six official memorials to the dead. Among them are the church at Nyamata, another in nearby Ntarama, and a museum called the Kigali Genocide Memorial. That museum traces the country’s long history of ethnic conflicts and examines the world’s other major genocides. It also serves as the resting place for more than 250,000 Rwandan victims.

Since January 2016, CNLG has contracted with PennPraxis to help develop a conservation plan for Nyamata.

“Memorial sites and all other evidence of the genocide have enormous political significance, and the Rwandan government rightly cares a great deal about physical evidence, including buildings, sites, artifacts, collections,” says Randall F. Mason, executive director of PennPraxis and chair of the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation. “The government is still in the process of building up the capacity to sustain these sites, and our work training and giving advice is meant to advance their ability to do it themselves.”

Mason is leading a revolving team of experts in building, materials, landscape, and textile conservation that has been visiting the site every few months during the last year and continuing into 2017. The clothes have become a priority, but their conservation is governed by a vexing set of constraints. First, they cannot be totally cleaned because the government is reluctant to interfere with their metaphorical value as material proxies for the victims and literal value as evidence of the genocide. Second, Mason and his team are committed to retaining the building’s passive ventilation, meaning they will not enclose and air-condition it. Finally, national policy states that the textiles must remain on site, so although the team would prefer to store the great bulk elsewhere, that is not an option.

Determining which pieces to clean, how and to what extent to do so, and what to do with the rest daunts even Julia Brennan, an experienced textile conservator more used to handling couture gowns, antique samplers, and ethnographic treasures.

“This work represents a broadening of the field,” says Brennan, a PennPraxis team-member who pursued a master’s degree in art history at Penn from 1983 to 1985 but never completed it. Brennan designed a similar conservation plan for clothing salvaged from victims of the 1975 Cambodian genocide that has yet to be funded, and galleries at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington and elsewhere also acknowledge the poignancy and intimacy associated with clothing and shoes. “But, in general, I don’t have a blueprint,” Brennan says. “I did a huge literature search, and there’s nothing out there, no conservation body or publication that covers taking care of genocide clothing in tropical climates and open environments. I’ve even been consulting with forensics people—because this is a crime scene.”

Attempting to prepare for what she would find at Nyamata, Brennan read books about the genocide and interviewed survivors. “But this, it’s just an overwhelming sensory experience. This is birds swooping in and out and mice and termites and a kind of sweet smell of bio-deterioration that’s like the rotting stuff of your compost,” she says. “It all reminds you of just why this clothing has been left there, and it’s a really important part of the witness-bearing of what happened there.

“This t0pography of rotting clothing is like a terrain with rivers and valleys and hills. And when you start teasing it apart and taking pieces out of it, you see the different fibers and different items,” she continues. “I’ve been told that survivors have gone back and identified pieces of clothing that belonged to their relatives. It can break your heart—nothing suggests daily life more than a child’s T-shirt or a mother’s best Sunday dress.”

When the killing stopped, three months after it began, extremist members of the Hutu majority had murdered an estimated 800,000 to 1,000,000 of their fellow citizens and neighbors. Mostly, the dead were members of the Tutsi minority, but some were Hutus who refused to cooperate in the blood-letting. A new crisis emerged on the heels of the decimation, as a Tutsi-led military effort gained control, forcing millions of Hutus to leave the country for camps in Zaire (since renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and other nearby nations.

But many of those refugees eventually returned and the country rebounded to a remarkable extent, both economically and socially. Through a traditional community-based trial system known as gacaca, named for the grass areas on which they were held, thousands of perpetrators publicly confessed their crimes before survivors and judges—confronting and acknowledging what had occurred and providing a critical step toward reconciliation. UN figures put Rwanda’s population at 11.8 million—more than before the genocide—and its economy expanded, with GDP increasing by about 8 percent annually between 2001 and 2014, according to the International Monetary Fund. A new constitution eliminated all references to ethnicity, and genocide education and prevention was widely integrated into school curricula, including visits to the genocide memorials.

The Penn Praxis effort at Nyamata is a more extensive and formalized follow-up to a research project that Mason led at Ntarama after being contacted by Katherine Klein, the Edward H. Bowman Professor of Management and vice dean for the Wharton Social Impact Initiative in late 2013.

Klein first visited Rwanda as a tourist seven years ago and has returnedrepeatedly to explore the country’s history and its “remarkably peaceful transformation and very interesting path to reknit and move on,” she says. “There’s an overall sense of commerce, security, and pride.”

When Klein toured Ntarama, she was deeply moved, but as she took in the damaged buildings, the garments hanging from the rafters, the piled bones, and the limited signage, found herself thinking: “This place is so important for the world, and it ought to be preserved for future generations. How much longer is this clothing going to last out in the open like that? How can this site meet the needs of both the survivors who come here to remember and mourn and the needs of international visitors?”

She found Mason by googling historic preservation, Penn.

“We had coffee and talked for about an hour,” she recalls. “At the end of the conversation, I told Randy that I was going to Rwanda in a few months and invited him to join me. He said ‘yes’ right away.”

Mason and Lacombe, who had recently graduated but not yet landed her job at the Peabody, consulted with architect Sharon Davis on how best to conserve the site at Ntamara in the face of planned work on visitor facilities. “We completed a short study and presented our findings to the architect to help solidify her work and make sure that some basic preservation principles were in place,” Mason says.

Davis, a New York-based practitioner whose work in Rwanda and other developing nations has been widely praised, wound up leaving the project before it was finished, and a Rwandan firm took over. According to Mason, the results “were disappointing, and included the overly aggressive restoration of heritage buildings, the introduction of new building elements, addition of a parking lot, and the destruction of village buildings next to the site.”

But Davis remembered Mason two years later, when she heard that the American Embassy in Kigali had received an Ambassador’s Fund for Cultural Preservation grant from the US Department of State and was interested in applying it to the Nyamata site. Davis offered to supplement the effort with a grant from her own non-governmental organization, Big Future Group, and also redirected other grant money she had received.

With about a $250,000 budget and greater responsibility, Mason and his team are hopeful that this time they can make a real impact. “Our relationship with CNLG has been quite positive, and training the staff, none of whom have conservation backgrounds, has gone extremely well,” he says. “Decision-making about the site is still sometimes mysterious to us—other projects have materialized that affect the site we’re contracted to work on, and lines of communication take some effort to understand.

“After a lot of twists and turns, though, we’ve negotiated a pretty effective solution to the problems that have arisen. At this point, my team is planning to implement the last phases of our work—prototyping the textile conservation process and writing a conservation plan that addresses the future of the building, the site and the collections holistically—and we’re committed to continuing our training role with CNLG for the long-term. We also are developing a relationship with the University of Rwanda to integrate conservation training into its architecture program.”

The twisting and turning strands of this emotional and complex project interweave with Mason’s own research interests. There’s the question of sensitively and sensibly managing a site that is of interest both to a nation in the midst of healing and to tourists (Nyamata Church, for example, has more than 150 “reviews” on TripAdvisor, while about 70,000 visitors tour the Kigali museum every year). Not to mention the notion of preserving the kind of disturbing, but hallowed, place where grenades tore holes into walls and machetes amputated limbs.

“Memorialization practices, which are part of preservation, have been reshaped by the notion of negative heritage,” Mason observes. “It’s an awkward term, but it sheds light on a newly significant, emergent way the public has of relating to the past. Tragedies, disasters, violence, discrimination, et cetera—they are all deeply part of the human condition, of human history. We choose the places that we preserve because they meant something in the past and represent something important in history. But to me the real point is not to create an archive but to give these places relevance in contemporary society.”

In the last few decades, negative histories and heritage have moved into the center of public life, Mason adds, through scholarship, increased recognition of the value of cultural diversity, the design of memorials, and the narratives of terrorism that have dominated societies in recent years. “There has long been a substantial intellectual interest in the Holocaust, for example, but these other negative turns of history also demand our attention,” he continues. (In 2015, more than 1.7 million people visited the Auschwitz-Birkenau Nazi death camps, a record.) “What I’ve been trying to sort out is how we value these negative turns of history as representations or documentations of the past, and how we use them for social or political reasons in the present.”

Mason first began exploring the topic in research that he and several colleagues conducted for the Getty Conservation Institute about 15 years ago on the development and management of various heritage sites across the world.

“My work was theoretical, but also included some case studies, and it’s become an important part of the teaching and practical work that I’ve done since,” he says. “The findings were that conflict does happen at these sites between these different values, and we should have a management system that is nimble enough and flexible enough to take them into account.”

As an example, he cites a Canadian quarantine station associated with Irish immigrants who came and died in great numbers because of a typhus epidemic. Parks Canada, the government agency, was taken by surprise by the emotionally charged nature of the public hearings, as unexpected stakeholders stepped forward to demand inclusion and others weighed in with specifics on the focus and themes of the memorial. “Dealing with that kind of unforeseen shift in the values attached to the site can be catastrophic if you’re not ready for it, or if you’re very closed-minded and say, ‘We only care about the buildings,’” Mason says.

Complicating it all, he adds, is an expectation of “memorialization where everybody’s voice gets included,” which has its roots in what some refer to as the “conspicuous compassion” of fleeting roadside memorials to accidents, or the impromptu gestures that sprung up after the collapse of the World Trade Center. “That’s a relatively new and powerful aspect that has affected the official memorials,” Mason says. “I wouldn’t say that it’s good or bad, just that there has to be some acknowledgement of those voices.”

In some cases, those voices have led to a rather pro forma kit of parts in many contemporary memorials—the individualization of victims, name by name; the water feature; the eternal flame. But sometimes the public instead calls for a de-memorialization, an erasure. The home of the girl whose murder inspired “Megan’s Law” was razed shortly after her 1994 killing and turned into a park. More recently, the town of Newtown, Connecticut, tore down Sandy Hook Elementary School, where a gunman killed 26 children and teachers in 2012.

The desire to eradicate unpleasant aspects of history is a “challenge you face with negative heritage,” says Evan Schueckler GFA’17, a master’s candidate who, with Mason’s encouragement, is examining aspects of the topic for his thesis. “It all comes down to questions of: who is the memorial for, and what purpose does it serve? Is it to help others learn, or to help the most directly affected to heal?” Traditional monuments didn’t usually suffer this dilemma. “They are purpose-built to stand in for and honor what happened,” he says. “Typically, though, the monument-in-the-square doesn’t satisfactorily address all of the facets of an event, and maybe because of that they tend to fade into the background; after a while we don’t even notice them.”

Mason served on a team selected as a finalist to design the Flight 93 memorial in western Pennsylvania, and the eeriness of visiting the site stays with him. “While the human remains and the debris had been taken away, there was a spot where the plane hit the ground and everything was essentially vaporized,” he says with a catch in his voice. “Yet the hemlock forest still stands, and as we walked through it, it was snowing and the sound and just being there made a big impact on me. I can remember it clearly, and yet it’s sort of difficult to describe.”

The Nyamata project involves considerations not just of artifact conservation (in this case, the clothing) but architectural and landscape preservation. The latter is Mason’s purview, which he discussed during a class devoted to the subject that Schueckler was taking in the fall. After filling in the dozen or so landscape-architecture students on the background of the genocide and his work there, Mason pointed out that so far, the government has viewed each memorial as a separate entity.

“I’m a big advocate of linking them,” he told the class. The killing happened everywhere in this lush, hilly country, he adds, pulling up a screen shot of a topographical map. “Here are the extensive marshes at the bottom of a hill. The Tutsi would hide in them during the day and come back to rest at night in the church.” Another image showed a clearing in the forest and a path to the marsh line. Whether this is a “desire path,” something created by the tread of many feet, he doesn’t know, Mason said. Moving on to a shot of the remnants of a bridge, he spoke briefly about how these sites lie between Kigali and a planned airport. “How will the construction impact these landscapes?” he asked. “Our goal is to sustain the sites materially through the years—conservation first, not tourists first.”

But in providing the government with the tools of conservation analysis and planning, Mason wondered if he would be able convey the importance of refraining from “trying to fix” something that “looks damaged or dirty or broken.” That might be difficult, especially when part of the government’s mandate is to mend a society that’s been torn asunder.

“It’s our job to help them understand the process behind how and why it’s deteriorating or performing badly,” he says, back in his office. “One of the maxims of conservation is: do the least harm. That’s a persistent point of our training. There’s a logic and a rigor that you bring to thinking about the issues and how to solve them. I often use medical metaphors, so you don’t go into the doctor’s office and say, ‘I want some surgery.’ You let the doctor collect data, analyze it, and apply his expert knowledge to make a diagnosis. Then you think about how to intervene.”

The clothes are a prime example, he says. “They’re grimy, they’ve been sitting out in the dirt and the dust for 20-plus years, they were never cleaned. So, the sort of common-sense approach would be to go in there and say, ‘Let’s wash this stuff.’ But if you wash it, you could be damaging, if not totally eliminating, important evidence of the genocide. There’s chaos represented in those clothes, and there’s blood and sometimes there are bone fragments.” In fact, he adds, some 40 percent of them are so tattered that they are no longer recognizable as garments.

To understand the deterioration and arrive at the best way to stop it, textile conservator Brennan has conducted all kinds of simulations, taking clothes and “getting them flat and wet and dirty, then letting them dry out and leaving them in a pile in my backyard where they’re subject to all different types of soiling,” she explains. “I’ve tested how they respond to vacuuming and surface cleaning, and looked at what kind of protective mesh allows me to remove what kind of soiling, from bird poop to mildew damage, but doesn’t remove all of the human information, like DNA.” The ultimate solution, she says, must be “sustainable, low-cost, low-tech, and duplicable.”

A further task will be to develop a system for storing and displaying the clothing. Although everything is up to the client, the current plan leans toward putting the semi-cleaned, recognizable garments back onto the repaired pews in the sanctuary. Severely deteriorated textiles will be packed in clear bins equipped with some sort of passive humidity system, such as drying beans used in seed-storage, then stowed at the rear of the sanctuary, which will be simply outfitted with a humidity monitor.

Enter Michael Henry EAS’77, an adjunct professor of architecture who teaches courses at Penn in building pathology and building diagnostics and is also part of the Praxis team.

“In any international project, we have to work to understand the culture of the place, the cultures of care, of remembrance and permanence and how the society looks at material culture,” he says. “And we have to consider the capacity and availability of utilities like electricity, information technology, mechanical equipment. We have to adapt our solutions and strategies to all of those factors.”

Henry is working on preserving the evidence of what happened there, such as the bullet-riddled roof, while stabilizing the building. But the main question has been “more about the environmental management of the textiles,” he says. “How do we manage them when they’re to be stored and displayed inside a naturally ventilated building?”

Meanwhile, Lacombe is thinking about possible materials and methods that might help protect the site.

“I’m looking into bird deterrents, dust mitigation, pest control, you name it,” she says. “I did the condition survey for the masonry, which was eye-opening. It’s a slow process of going through each brick and determining what damage was done by a bullet versus what’s the result of time just crumbling away at it. I’ve learned a lot—I’m still new to this. Even Michael and Randy would say that they are constantly learning, so to be along with them has been very inspiring.”

Another-game changer for Lacombe, despite the language barrier, has been the teaching aspect. “I really love being able to connect with people and feel like I’m turning on a light bulb. I’ve spent a lot of time with the CNLG staff just sitting and talking about preservation philosophy and how it can be applied to Nyamata. One afternoon we were discussing building conservation and how materials work together. They’re all trained in the sciences, so when we actually did run the tests and tried to figure out why, when you turn the light on at the same time every day, the humidity drops but the temperature rises in one spot, they got really excited about how to fix it. ‘Well, maybe if we use LED lights …’”

“The contemplative and craftsmanship-like nature of this kind of on-the-ground work, done by people in groups, is where cultural heritage protection needs to go,” Brennan muses. “Think of Syria or Afghanistan. If people can work together and do something constructive while taking care of their heritage, I think that’s going to offer them a lot of hope and connection.

“For the larger field of conservation of heritage,” she continues, “I hope it becomes embraced as a project that is about peace-building. I feel an ethical obligation to try to protect the remains of a horrendous piece of our shared humanity. I’m putting every ounce of my effort into putting together something that is going to work and have applications elsewhere.”

Frequent contributor JoAnn Greco is a freelance journalist in Philadelphia.