At the very end of the panel discussion on “Ethics and Integrity in the Historical Profession: Plagiarism, Business and the Media,” history-department chairman Dr. Jonathan Steinberg turned to his fellow panelist and said, “You have the last word. You started this.”

“No, I didn’t,” said Dr. Thomas Childers.

Since January, the Penn history professor has found himself thrust into the media spotlight following the revelation that popular historian Stephen Ambrose had plagiarized his work.

Childers, Steinberg, and a third history professor, Dr. Kathy Peiss, discussed the Ambrose case and related issues before an audience of about 60 people in Houston Hall in March. The event was sponsored by the University Honor Council, along with the offices of the president and provost, the School of Arts and Sciences, and the history department, in the hope that it will be the first in a series of campus dialogues on ethics.

Childers had known for some months that Ambrose had lifted passages from Childers’ 1995 book, The Wings of Morning, and used them in his recent bestseller, The Wild Blue. But the plagiarism didn’t come to wide public attention until a January 14 story in The Weekly Standard touched off a media frenzy. Both books are about bomber crews operating over Germany during World War II. Ambrose footnoted Childers, but neglected to put quotation marks around verbatim phrases in his book. Under media attack, Ambrose promised to correct future editions. And Childers, who had included The Wild Blue on the reading list for a course he taught this spring, said he would remove Ambrose from his syllabus next semester.

Following that initial revelation, the press eventually came forward with evidence that Ambrose had lifted others’ material in four more of his books, and also accused historian Doris Kearns Goodwin of plagiarism in her book The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys. (Goodwin, a Pulitzer Prize-winner for her 1995 book on Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, No Ordinary Time, and a frequent guest on the PBS “NewsHour” and other news programs, drew hundreds of Penn students to a talk she gave on campus in February as part of the Fox Leadership Series [see story, p. 23].)

Despite the charges leveled against two of its most noted practitioners, Childers maintained that popular history as such is not to blame for plagiarism. “I don’t believe at all that there is a problem with popular history,” he said, commending Ambrose, Goodwin, and John Adams biographer David McCullough for getting in touch with a broader audience and avoiding specialization. “Reaching out should be part of what historians seek to do.”

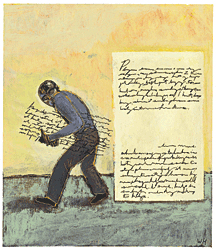

Nonetheless, Childers was hurt and disturbed by Ambrose’s actions and motives. “Your choice of words—that’s you,” he said. “That’s your personality. It’s your craft. It’s your art.”

Childers spoke of Ambrose’s methodology only towards the end of the discussion, quoting him in jest: “I’ll paraphrase this very closely—‘Look, I’m not writing a Ph.D. [thesis].’” That statement did not sit well with Childers. “This wasn’t a slip-up. It wasn’t working under pressure. It was a method.”

While he professed surprise at the media’s ongoing obsession with the story, Childers empathized with student anger, noting that he has received e-mails from undergraduates across the country. “All universities have strict honor codes,” he said. “Students have a right to be outraged over this. One can’t flunk Stephen Ambrose for the course.”

Kathy Peiss, an expert on women’s history and the history of sexuality and gender in the United States, came to Penn in September after teaching at the University of Massachusetts for 15 years. Noting the proliferation of celebrity historians and talking heads on television shows, she said, “We’ve become content-fillers for news and entertainment.” She herself was the chief consultant earlier this year for the PBS documentary “Miss America.”

Peiss raised another moral issue concerning the uses made of scholars’ ideas. As the author of Hope in a Jar: The Making of America’s Beauty Culture (published in 1998), she finds herself regularly approached by businesses. Banana Boat is one of her suitors. “Is taking money for that tainting [my work]?” she asked, “Who owns the ideas once they are filmed?”

She described plagiarism as both a “property crime” and a “taking of reputation.” The word comes from the Latin for “to kidnap” and “to seduce,” she noted. “It suggests something of the body and the self is being taken.”

Steinberg admitted that there is a fine line between carelessness and plagiarism. For example, after having read an untold number of texts on Italian fascism, was his lecture that morning in “Europe: 1890-1945” purely his own wording?

“There’s a problem with what one actually remembers,” he said. “Slips of memory and data retrieval are understandable, so plagiarism’s a complex issue.”

The Internet facilitates other gaffes. On Blackboard—a Web-based course manager that lets students interact with professors from their home computers—he’ll pull a passage from the Columbia online encyclopedia, paste it on to his class notes, and forget to site the URL. “It’s easy to slip into bad habits. Information is now available in a way it’s never been before.”

If an Ambrose-type case turned up in Penn’s history department, what would Steinberg do? “Each case really is different,” he said. “This is not a copout. I guess you set up a committee of your faculty and you investigate. I think you have to behave as if you were a court of law. I can’t see any other way of proceeding. I think you have to follow due process.”

—Aliya Sternstein C’02