How debate instruction can bolster public education and revive democracy.

By Robert Litan

If there is one takeaway from the history of presidential debates that is beyond dispute, it is this: these are not real debates, but a series of well-rehearsed sound bites, a low standard that this election year’s debacle did not come even close to meeting.

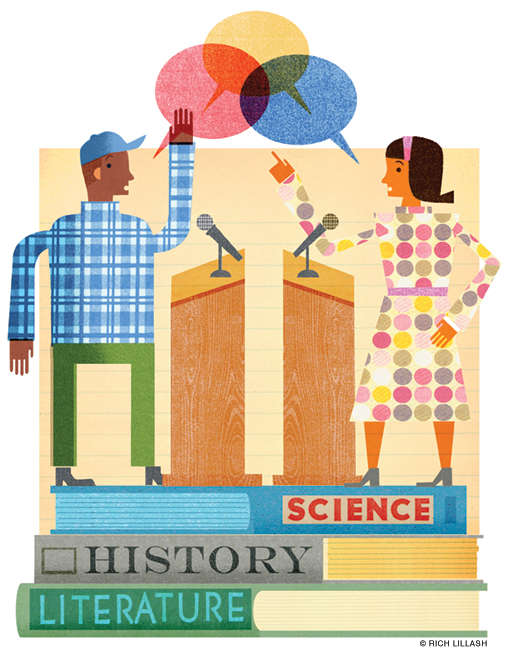

In real debates, the participants offer reasoned positions, backed by evidence, in civil discussion, without name-calling, in speeches that last longer than 60 or 90 seconds. Competitive debaters in high school and college not only learn how to do this well, but to argue multiple sides of a topic in different “rounds,” which forces debaters to appreciate that most issues are far more complicated than they appear on social media or cable TV.

I know, having debated competitively in high school and at Penn 50 years ago, that learning how to debate can be a life-changing experience. It was the only thing that ended my stuttering, while greatly improving the research and reasoning skills that have benefitted me throughout my career.

But it did not occur to me until two and a half years ago—when I read a newspaper article about high school students from my home state of Kansas winning the national high school debate championship—that the lessons learned in debate could be used to improve the quality of education more broadly, with some important side benefits: reducing the political polarization that threatens to tear our society apart while enhancing important workplace skills that can lead to higher-paying job and career trajectories.

Although it is not realistic to expect every student to become a competitive debater, everyone can learn at least how to speak clearly, logically, and with evidencein front of others, and do so with equal proficiency on two or more sidesof any topic. They can acquire these skills by learning debate techniques, not as an after-school activity, but as an in-classroom device in nearly all subjects in middle and high school.

This isn’t just a dream. It’s actually been happening in over a dozen middle and high schools serving primarily minority students in Boston and Chicago through the pioneering efforts of former debaters Mike Wasserman and his colleagues at the Boston Debate League (BDL) and Les Lynn in Chicago. Both independently have been teaching and mentoring teachers in “debate centered instruction” (DCI) for about a decade.

Here’s how it works. Typically, classes are broken up into small circles of six or eight people; asked by the teacher to consider a “claim” from literature, history, or science; and then charged with marshalling evidence and reasoning, drawn from assigned reading or elsewhere, to support or refute the claim. The teacher roams the room, listening to each group. Eventually, everyone in the class is required to participate orally in the discussion, and ideally to be able to refute critiques. Name-calling and ad hominem attacks are verboten. Students learn to speak respectfully, clearly, with evidence and reason.

I’ve seen how all this plays out in schools in both cities. The classes buzz with excitement, students enjoy the give-and-take, and even the most hesitant or shy ones eventually come out of their shells. Both BDL and Lynn have data showing that both test scores and measures of student engagement have risen substantially since the adoption of DCI.

Of course, more rigorous evaluations would be useful. A team led by University of Virginia education professor Beth Schueler is now conducting such a study of the hundreds of students who have passed through approximately a dozen schools, assisted by the Boston Debate League, over the past five years.

There are several reasons why more formal statistical studies should confirm the “before-after” improvements in student performance that the BDL and Lynn report. One reason is that learning by debating is a lot more fun for many students than listening passively to lecturers.

Another reason is that people of any age are more likely to understand and retain information that they must master and be able to communicate orally to other people than by regurgitating it on a test.

Studies of competitive debaters in Baltimore and Chicago show academic improvement, even controlling for “self-selection” (the stronger inclination of better students to engage in competitive debate). Moreover, because these studies concentrate on minority students, the same populations that are currently benefiting from DCI in Boston and Chicago, they suggest that broader exposure to debate in the classroom should help narrow persistent Black-white educational performance gaps.

There is also ample reason to think that the benefits of DCI would extend past formal schooling. Knowing how to speak with confidence, backed up by evidence, is a skill that employers consistently say is lacking in students coming out of high school and college. DCI would directly address that problem. Debate training would also be valuable for future entrepreneurs, who must be able to pitch their ideas to a variety of audiences—investors, lenders, potential employees, and customers.

Moreover, a citizenry trained in debate techniques would be very different from the one we have now. Imagine a nation of voters who can see through campaign slogans and misinformation, and appreciate the nuances of public policy challenges because they have been trained to seek out facts and advance reasoned arguments in defense of conflicting positions on multiple subjects. A body politic trained like this at a young age in turn would demand more of those seeking and holding elected office than the simple slogans or labels that show up relentlessly in political ads (most of them negative) and on social media. I believe our nation would be far less politically polarized, our politics would not be so mean-spirited, and our elected officials would be more inclined to compromise and get things done.

School districts throughout the country need not wait for all the evidence to come in before experimenting with this simple but powerful instructional technique, since enough is already evident. Even some basic college courses can benefit from the approach—with debates conducted in breakouts of large lecture classes led by graduate teaching assistants.

To be sure, many teachers, school superintendents, and local school board members are suffering from “reform fatigue” and may be hesitant to adopt yet another method of learning. But DCI instruction is not hard for teachers to learn. Initially, teachers without debate experience can be taught how to use the claim-evidence-reasoning paradigm in their classes through one week of summer instruction, using funds already earmarked for professional development. Once initial cohorts of teachers are trained, they can train others in their schools. If a school has a debate coach, he or she, with modest additional compensation, can provide ongoing assistance to teachers throughout the school year, as can the teachers interacting with each other in breaks during the school day, as I witnessed in both Boston and Chicago.

Our highly polarized democracy is in trouble. Our schools must do a better job of educating students—especially disadvantaged minorities and students from low-income families. And all students need a “want-to-learn” mindset, which they are much more likely to acquire if school were a lot more fun and engaging, so that they will want to continuously upgrade their skills to meet constantly changing employer demands. Debate centered instruction can help meet each of these challenges.

If you are the parent of a school-aged child, you can advocate for DCI before your local school board or your state education officials. By doing so, you can give the next generation the skills they can use throughout their lives, for themselves and to help save our democracy.

Robert Litan W’72 is a non-resident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, a partner at the law firm of Korein Tillery, and the author of the new book, Resolved: Debate Can Revolutionize Education and Help Save our Democracy (Brookings Press, 2020), from which this essay is adapted.