At a campus lecture, a New York Times editorial writer recalls his harsh introduction to the “otherness of being Black.”

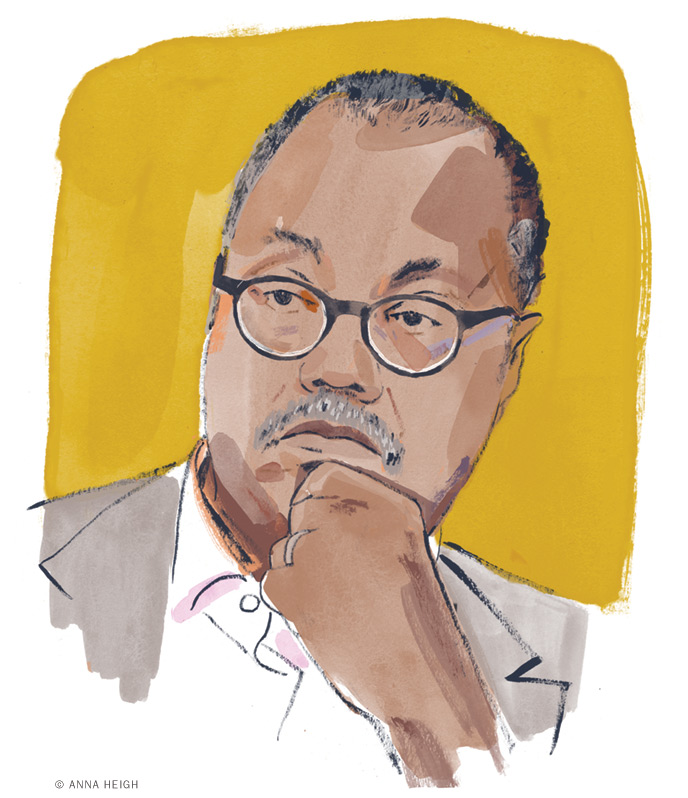

“I thought for a time that I was going to be in the professoriate,” said author and New York Times editorial board member Brent Staples, “but then I got a taste of directly engaging the public with my writing.”

Staples, author of the memoir Parallel Time: Growing Up in Black and White and winner of the Pulitzer Prize for editorial writing in 2019, was on campus in late February to deliver the inaugural W. E. B. Du Bois Lecture in Public Social Science in an event hosted by the Department of Sociology in collaboration with the Annenberg School for Communication and the Center for Africana Studies.

In conversation with Tukufu Zuberi, Penn’s Lasry Family Professor of Race Relations, Staples reflected on his first time being aware of the “otherness of being Black” and its role in shaping his writing career. His remarks have been slightly edited and condensed. —JP

“I grew up in Chester, Pennsylvania, right down the road [from Philadelphia]. It was a steel and shipping town. When I was growing up, there were 66,000 people there. It was, in fact, quite a lively place, and at its peak the shipyard in Chester employed 40,000 people in a town of 66,000. And as shipping disappeared, you know, 40 became 30, became 20, became 10, became none. So as a young person growing up there and absorbing the inevitability of that, I thought to myself, You know, you must leave this place.

I got into a small college called Widener; it’s a university now. I didn’t really have a specific mission, but I knew I wanted to write, and I knew this was going to give me a chance to write. When I got close to graduating, I applied for some doctoral fellowships—once again, not with a big plan, but my idea was to project myself into the world. I ended up at the University of Chicago.

I had grown up in a town where everybody knew me. My father had three brothers there, and so everybody knew us all. So the first time I went to a place where I was unknown was in Hyde Park in Chicago. I’m 22—that’s pretty old, actually, to find this out—and I was walking down the street at night, and I began to notice that people who saw me would cross the street. Or when I crossed in front of a car at a stoplight the people would hit the door locks—not power locks like you have now, they had to hit them. Thunk, thunk, thunk, thunk.

It was my first kind of belated awareness that people saw me as dangerous. You know, this big Black guy walking in the street—doing nothing, really, but the people saw me as dangerous. And I started to process that and work with that idea, and years later I wrote an essay entitled “Black Men and Public Space.” In some books published it’s called “Just Walk on By: A Black Man Ponders His Power to Alter Public Space,” and that’s in, I don’t know, four or five million copies right now. It’s really all over the world. But what it’s about is trying to grasp and understand the experience of being perceived as a monster, as a dangerous person, when in fact you had no ill intent toward anyone. That experience in the new white world, I think, launched my writing career—because I really needed to actually get that down on paper and wrestle with it to some degree, understand how it made me feel, and how the other people were feeling. So that was sort of my introduction to the otherness of being Black.”