A scholar pursues harmony—and gender justice—in Islam.

By Amina Wadud

I came to Penn in 1970 as Mary Teasley. My father, a Methodist minister, had named me Mary to recognize the sanctity of the mother of Jesus. By the time I graduated with a Bachelor’s of Science in education, my name had begun to change to reflect my acceptance of Islam.

Today I go by the name Amina Wadud. Aminah was mother to an ordinary Arab man whom Muslims believe was visited by God with divine revelation and a charge to establish truth, justice, and peace on the earth. He was Muhammad ibn ‘Abd-Allah. Allah translates as (the) God. Wadud is one of 99 descriptions of this single Ultimate Essence. It means “loving.”

Entering the religion of Islam in 1972 proved to be the greatest milestone in my life. I began my study of Arabic and Islamic Studies before I graduated and moved abroad with my husband and first child (now a third-generation Penn graduate). Since then, I have lived in two other countries and have traveled on behalf of issues of Islam and justice reforms, delivering about 200 lectures, presentations, workshops, and other consultations to challenge gender inequities practiced by Muslims, sometimes even encoded by stringent legal codes under shari‘ah, or Islamic law.

My scholarship and activism originate from the Divine revelations to the Prophet Muhammad in the 7th century, the Qur’an. Islam is a continuation and conclusion of the Abrahamic scriptural traditions of Judaism and Christianity. The three share a belief in one God. Like all religious traditions, they were practiced, interpreted, and developed by fallible human beings: God’s creation of free-willed human agents on the earth. Most, if not all of them male.

Liberation, feminist, and womanist theologies have challenged patriarchal notions with the larger perception of a Creator, unlimited by historical human constructs, in ongoing living realities of truth, harmony, and justice. I have played an important role regarding these reconstructions in concert with women and men, Muslims and non-Muslims.

My first major contribution was the publication of my dissertation research in a book, now called Qur’an and Woman: Rereading the Sacred Text from a Woman’s Perspective, Oxford University Press 1999 (with the earliest editions published in Malaysia in 1992). Unknowingly, I had written the first gender-inclusive exegesis of the Qur’an. Its publication and my simultaneous activities within the global communities of Islam have brought me international prestige as a scholar and activist.

Before the movement of Western colonialism, the Muslim empire was one of the most powerful and pluralistically integrated across vast geographical regions and a plethora of cultures, languages, and peoples. As the modern nation-states emerged, the inheritors of the Islamic tradition were ill-prepared to manage this transformation, especially as still dominated by a matrix of Western philosophical, epistemological, political, and economic constructs. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, seeds of Islamic modernism and reform were planted to eventually grow and sometimes mutate into the complexities of living Muslim realities.

When the most extreme forms of these mutations destroyed the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, the words Islam and Muslims aroused interest in many sectors of the global community, but especially in North America, taking on a force greater than the thousands of lives that ended in the rubble of these collapsed symbols of Western dominance and control. Once “Islam” and “Muslims” became the West’s Public Enemy Number One, the internal strife in the process of modern reconstruction was also laid bare. The erroneous and over-simplified conclusion was that “Islam” is unjust.

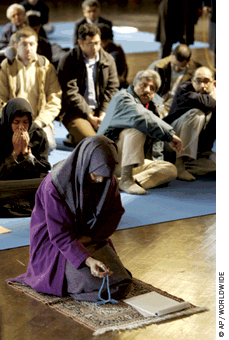

Since 9/11, my particular dedication to issues of gender justice from a pro-faith, pro-feminist perspective has been caught up in the frenzy and sensationalism of global mass media. On March 18, 2005, I stood in a hall of a New York cathedral before a congregation of Muslim women and men from different parts of the world and fulfilled the role of religious leader in the required Muslim daily prayer.

In the weeks that followed, my email inbox was inundated with messages of praise and rebuke, and anonymous threats made against me on the Internet had police tracking license plates near my home. Citing security fears, my university employer asked me to stay off campus for the semester and teach classes over a video link. Dozens of reporters pressed for interviews.

Conflicting tendencies and inclinations inside the Muslim world, as well as Western sensationalism have both held the issue of Islam and Women as one of several major agendas proving or disproving the legitimacy of a particular individual, group, community, country, even all of Islam itself. My own activism and scholarship became part of the divisive discourses over Islam and Muslims. We are divided—no: we are fragmented—as Muslims. In order to discover, unveil, and build the light of harmony that is reflected in these fragments, many challenges will have to be grappled with and peacefully resolved.

The mid-day Friday prayer, salat-al-jumu‘ah, is named for its mandate to be performed in congregation. Such congregations have been so overwhelmingly male for more than 1,400 years that it seemed to some as if my leadership on March 18 was a deviation from the “true” faith tradition. A closer look shows that no text in the Qur’an forbids women-led prayer. Centuries of Muslim (male) scholars argued for or against women’s ritual leadership—never reaching a consensus. The majority opinion against women-led prayer exists alongside important contestations of that opinion, both integral to the Islamic intellectual history. In fact, women have been leading mixed male-female congregations in prayer in discreet corners of the Muslim world since the 20th century. Indeed, I was previously invited to deliver the sermon before the congregational prayer, the khutbah, as early as 1994 at the Claremont Road Mosque in Capetown, South Africa.

The sensation caused by media coverage of the March 18th prayer however, leaves many questions unanswered for Muslims and non-Muslims. Bringing out the worst and best extremes, it leaves masses of Muslims in the middle to ponder the ultimate question: Is God, Allah, so powerless that one woman can dismantle His/Her or Its omnipotence in a single act?

For those working on the issue of justice and reform, the resounding answer is No. For Muslims, Allah is, has been, and will continue to be the Ultimate Reality and Principal advocator of universal harmony. Now, as it always has been, it is up to human beings to use our agency in creating a world in which that harmony and justice is practiced at all levels of global human activities.

Dr. Amina Wadud CW’75 is the author of Inside the Gender Jihad (OneWorld Publisher/Oxford), due out in June.