The Penn Athletics Wharton Leadership Academy aims to turn varsity athletes into lifelong masters of team dynamics. Among the obstacles? Snowplow parenting, youth sports, self-reinforcing gender stereotypes, and the culture of leader-worship itself. Oh, and possibly a rattlesnake or a freak mudslide.

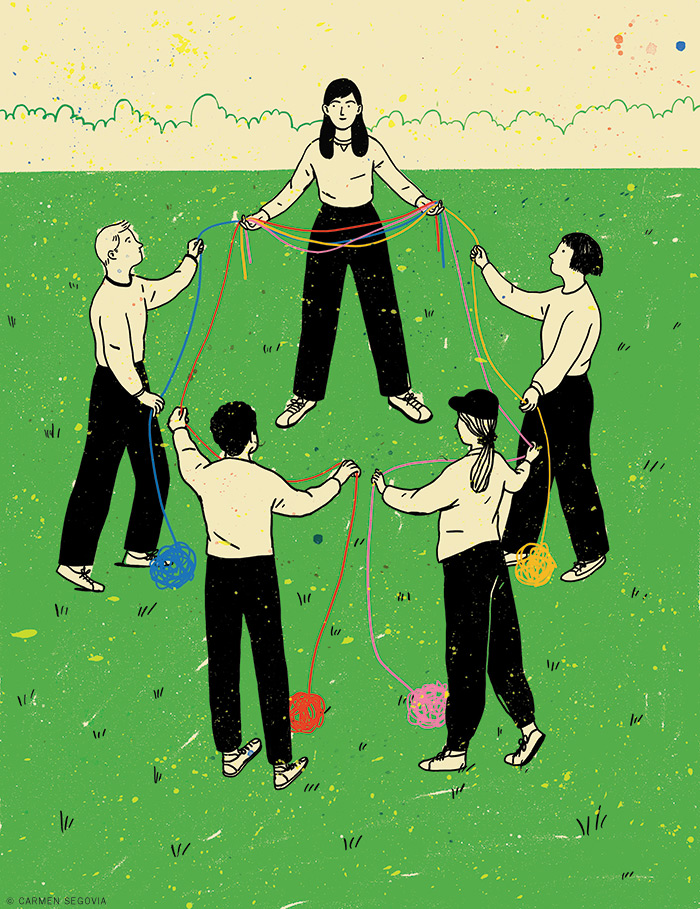

By Trey Popp | Illustration by Carmen Segovia

It’s definitely not going to rain.

That was the word going around a meadow below Shawangunk Ridge as a Wharton Leadership Ventures team prepared for the arrival of roughly 20 Penn student-athletes on a bright mid-August morning in upstate New York.

It passed from Jules Roy LPS’19, who spent 22 years in US Air Force Special Operations as a rescue specialist before joining WLV in 2015, to Dave Ritchie and Zak Shaw, two WLV partners who’d just touched down after roundabout journeys from their home base in New Zealand. Gonna be hot and clear, guys. Remember sunscreen. It bounced from Erica Montemayor LPS’20, who came to WLV from Outward Bound in 2016, to Kiko Guzman and Gabriel Becker, a pair of longtime program affiliates from Chile.

It reached your intrepid reporter around midday Thursday, as a mixed crew of wrestlers, rowers, gymnasts, and softball and women’s lacrosse players dumped their bags at the edge of the clearing. Not that I needed to be told. I’d seen the forecast. I’d even gone the WLV team one better and left my Gore-Tex at home.

The students had largely been kept in the dark about what the next 30 hours would bring. Their packing lists telegraphed the presence of deer ticks. They’d signed liability releases covering everything from fatal mudslides to “dangerous contact with rescue vehicles or aircraft”—but when’s the last time a sentient human actually read every sentence of an online waiver? What they knew is that their first two years in the Penn Athletics Wharton Leadership Academy (PAWLA) had been building up to this junior-year excursion.

They learned a little bit more after gathering in a big circle where Roy laid out the mission of WLV, which is housed in Wharton’s McNulty Leadership Program [“Gazetteer,” Nov|Dec 2016]. “Our bread and butter is to build programs where we bring people into uncomfortable situations,” he told the group. “So we get to go through this experience together, and then we get to talk about it. We pull out valuable stuff and then repurpose that stuff into our real lives—figure out how it fits, both on the field of play, and beyond the field of play when we leave Penn.”

Then the students heard from Rob Griffiths, a local guide tasked—for the moment—with alerting them to the presence of poison ivy, rattlesnakes, and copperheads. Thinking better of a crash course on species identification, he left it simple: “I would say just don’t try to pick up any kind of snake.”

After a few more icebreakers, the athletes formed five-person groups (engineered to split up as many varsity teammates as possible) to discuss some of their individual goals and fears pertaining to the still-mysterious “mission” awaiting them at dawn. Intricately structured by WLV facilitators, these exchanges doubled as training modules for the following month, when each junior would be handed a group of freshman athletes to induct into the multiyear program. They also served as brief, tentative bonding sessions ahead of a pre-mission competition whose results would influence the next day’s proceedings.

The crux of that contest was easy enough to guess from the sight of Dave Ritchie tossing tent sacks onto the grass. Just how foreign this form of shelter was to nearly every athlete on hand would soon be revealed. But for the moment all eyes had shifted to the sky, whose pale blue had been blotted out by a fat-bellied cloud that now tore wide open, pounding the meadow with a staggering downpour of rain.

The venture began at that instant.

If the students wanted to know who to thank for being summoned here in the precious waning days of summer, the chief culprit was Dave Pottruck C’70 WG’72, who catalyzed the establishment of PAWLA in 2017 with a $1 million gift. (Ben Breier C’93 W’93, the only three-year captain in Penn baseball history and at the time the CEO of Kindred Healthcare, was another key donor and supporter. In 2021, Pottruck contributed an additional $6.3 million.)

A three-year varsity football starter who also captained the wrestling team, Pottruck credits collegiate athletics for fostering the leadership skills that ultimately carried him to the CEO chair at Charles Schwab in the early 2000s. But he says it wasn’t until after he graduated—and worked as an assistant coach of the wrestling team while pursuing a Wharton MBA—that those lessons clicked.

“I saw my wrestlers excel or disappoint not because of their athletic skill but because of their mental preparation, or their belief in themselves, or their ability to get the most out of their athletic gifts,” he told me. “And I began to appreciate that this is the way life is. Life is not just about the gifts you’ve been given, but how to maximize those gifts—and how you maximize the performance of everyone around you.” Wrestling’s one-on-one nature lacks football’s explicit team dynamic. “But you can only be as good in wrestling as the quality of the competition you have every day in the practice room,” Pottruck pointed out. “You get better—or you don’t—based upon the contributions of your teammates. Because you don’t succeed on your own as a wrestler.”

Which isn’t so different from corporate life.

“In business, and in sports, you’re competing against other teams—other companies—but you’re also competing internally against other people who want to get promoted. There are eight guys doing a job in a department, and one gets promoted because the boss leaves for another role. And the question is: Who’s going to be promoted?” Pottruck said. “I wanted to be that one who got promoted. But how do you do that in a way where you’re doing it not because of your selfishness but because of your generosity? Not because of your ego but because of your graciousness? How do you distinguish yourself on the basis of those kinds of qualities as opposed to self-serving, self-aggrandizing qualities? That took some learning for me. It’s almost a Zen thing—that you succeed by lifting all of those around you, rather than just by trying to lift yourself. And good bosses will see that, and that’s the ultimate quality that people are looking for in leaders to be promoted within any organization.

“My initial training in that was as an athlete,” he concluded. “But my awareness of it was magnified when I stepped back from the field of competition and I was coaching. It was then that I really began to appreciate: Oh, that’s what’s going on, that’s how this works.” Why not make those lessons more explicit for current student-athletes, he thought, by tapping Wharton faculty who specialize in leadership and team dynamics?

PAWLA took shape around conversations between Pottruck, former athletic director M. Grace Calhoun, and her then deputy Alanna Shanahan C’96 GEd’99 GrEd’15, who succeeded Calhoun as athletic director in 2021 after a stint at Johns Hopkins University [“Sports,” Jul|Aug 2021]. Head women’s lacrosse coach Karin Corbett emerged as a natural choice as the inaugural director. Having led her program from the Ivy League basement to national renown since taking the reins in 2000, Corbett had already incorporated explicit leadership training—complete with assigned reading—into her coaching. Enough so, in fact, that a player named Lauren D’Amore W’17 had taken it upon herself to connect her coach with the professor of her required Wharton undergraduate gateway leadership course, Anne Greenhalgh, who is deputy director of the McNulty Leadership Program. By the time PAWLA got off the ground, Corbett had taken a couple Wharton leadership classes and told Calhoun that if Penn Athletics ever launched a broader initiative, she wanted in.

Corbett had a specific motive. “Over time, I’ve noticed that the kids coming into our program have less in the way of leadership skills. And it seems to keep going down every year.” Indeed, before the rain squall, she had described PAWLA’s purpose to the big circle of athletes in those very terms. “I’m not going to blame you guys,” she said. “What I’m going to blame is a lot of youth sports.

“When we were growing up, we used to play pickup in the neighborhood,” Corbett explained. “We didn’t have cellphones, so you had to call somebody’s home phone and say, ‘Hi Mrs. So-and-so, is Johnny home? We’re going to have a wiffleball game.’ And you’d have to get Johnny to bring the bases, and then call around to everyone else, and get everybody there. And if Johnny forgot the bases, you’d be like, ‘Hey, you have to go back and get the bases or we have no game’—so you held a kid accountable at a young age. And there were no adults running any of it. So you might fight: Amy could slide into home and say she was safe, and you’d say she was out, and you’d argue about it—but how do you continue the game?

“And I really believe, especially as I now have a 10-year-old,” she went on, “that youth sports robs kids of owning the games: of setting it up, making the rules, picking the teams, getting kids out, dealing with the conflict, holding people accountable. Kids rise to the top of leadership because they’re comfortable in it … but I think youth sports has put an adult in your life” every step of the way: from the maximalist parents forever shepherding their children to club practices and showcase tournaments and the right prep schools—fetching forgotten cleats along the way—to the coaches who direct every drill and mediate every conflict that arises. “So the personal responsibility, the leadership of just stepping into a team when you’re little with nobody guiding you—you don’t get that opportunity as kids these days,” Corbett concluded. “So what I’ve found as a coach is, I’m expecting my seniors to know what they’re doing, and they don’t.”

Senior leadership is particularly critical in the Ivy League, whose limitations on official varsity practice time create a structural disadvantage relative to other Division I teams. “For us to compete nationally,” Corbett told me before the trip, “our kids have to practice. So we have captains’ practices. The kids run it—so they have to be able to run that where they come on time, and they have a standard for how they practice. And are they teaching?—because they’ve learned how the sport goes” at the collegiate level, where elements like shot clocks and more permissive physical contact changes the complexion of some sports, including lacrosse. Over the years, in various team contexts, Corbett noticed a worrisome trend among her seniors: “They’re saying less. And we’re asking too much of them because they don’t have the skills.”

Whether the blame lies with the intensification of youth sports, “snowplow parenting” that clears away obstacles, or the simple reality of hypercompetitive college admissions, it’s safe to say that the road to Ivy League athletics no longer runs through pickup wiffleball fields (if it ever did). Consider that no fewer than eight current members of the Penn men’s soccer team—not traditionally a national powerhouse—came up through Major League Soccer franchise development academies, whose rigidly structured training programs demand exclusive devotion to that single sport and whose best performers have ultimately commanded multimillion-dollar transfer fees to top-flight European clubs. “My Saturdays as a kid,” lacrosse player Maria Themelis told me on the bus ride up, “were like going to a soccer game in the morning, then a basketball game in the afternoon, and then a lacrosse practice or game at night.”

Adult-mediated sports loomed equally large in many of her peers’ memories.

“I absolutely think Karin’s onto something,” her teammate Sophie Davis reflected later. “And as much as I hate to say it, I think a lot of us are products of that.” Though Davis credited her parents with fostering her independence and characterized her own youth sports experience positively, “I had friends whose dad was their coach for 10 years. You’re just being handheld through everything.

“Our team had a struggle with that this past season,” she continued, reflecting on a rare losing campaign after two scuttled seasons (due to the Ivy League’s unusually severe COVID response) that sapped the squad’s leadership ranks and cohesion. A couple of the team’s stars transferred to other marquee programs, leaving a vacuum that may have posed a particular challenge for a women’s team. For in Davis’s view, adult encroachment into American childhood can be especially stunting for girls, who are already steeped in a culture that’s often hostile to female assertiveness.

“It can be hard for girls to be straightforward, be direct, to tell someone something they don’t want to hear,” she observed, “because then people are like, ‘She’s such a bitch.’ If a guy does that, no one cares—and that’s great, that’s how women need to be!” Davis exclaimed. “But that’s not how we were raised. And when you add: Oh, the coach is going to handle it—or, The coach, who is my dad, is going to handle it—make sure everyone gets equal playing time, and make sure so-and-so doesn’t get her feelings hurt,” there’s even less space for the players themselves to step up and try to influence the behavior of their peers. “And I think it creates a cyclical dynamic,” she added. “Because if you can’t say something to someone and be direct, then you also can’t receive it—when someone does do it do you, you’re like, ‘Oh, she’s being such a bitch, I would never do that!’

“And we find so much more validation in how our friends think of us,” she noted. “That’s why being on a team with your best friends in the world is scary, to then have to get over that hump of: Oh, the last thing I want in the world is for my best friend or roommate to think I’m being mean.

“I think I’m a very straightforward and direct person, but I still struggle with it,” Davis concluded.

The small-group sessions on the meadow revealed that fear of conflict—and anything that might trigger it—was pervasive, especially although not exclusively among the women. (It bears mention that female athletes outnumbered males four to one on this venture, due mostly to the heavy participation of women’s lacrosse players among PAWLA’s spring-sports cohort. The fall-sports iteration was split evenly.)

“I don’t want any situation to be misconstrued, and I think a lot of conflict starts that way,” said lacrosse midfielder Aly Feeley. “Also, our generation has a heightened sense of how other people are viewing you. I think it has to do with social media. I never want people to think of me in a bad way, or think I was trying to do something mean or something to upset them.”

Corbett—who is no stranger to gender double-standards—sees half of PAWLA’s battle as equipping student-athletes to overcome these kinds of discomforts, because they impede what she considers the lifeblood of any team or organization: the enforcement of accountability. If players can’t hold one another accountable—for executing game plans, for giving 100 percent in practice, for the state and mood of the locker room, for comportment off the field as particularly visible representatives of the University—then success will be rare and fleeting. The other half of the battle is making participants more resilient to failure, which is a first-time experience for many collegiate athletes who have only ever been the best on their youth teams. So PAWLA’s freshman-year programming breaks the big question—How can I get more playing time?—into practical steps: How can I identify my weaknesses? How can I formulate specific and effective goals? How can I manage my time to achieve them? How can I contribute to the team even from the end of the bench?

What struck me most while talking to Corbett was how seldom she deployed anything resembling the rhetoric of the Transformational Leader, that iconic figure who bends the will of everyone around them in feats of charismatic inspiration. Instead she continually emphasized concepts like responsibility, accountability, self-awareness, community, and trust—terms that are certainly germane to leadership but are more directly rooted in organizational dynamics. Interviews with PAWLA-affiliated Wharton faculty went the same way, centering scholarship on the structure, management, and performance of organizations.

“When we talk about leadership, notice that we actually don’t talk about ‘leaders,’” Anne Greenhalgh told me. “If you have a whole host of ‘leaders’ who all think they’re in charge, that is a recipe for disaster. But if you have a host of people who are committed to leadership—to the act—you have hope, I think, of a high-performing team. It is about stepping up—and it’s also about following: Knowing when to step up, when to step back, when to step aside.”

Dave Pottruck casts the mission in similar terms. “We don’t try to model how you become a celebrity CEO—how you give interviews to the Wall Street Journal that focus on your tweets and your grandeur. That’s not what we teach,” he emphasized. “Great leaders revel in team success rather than their own. Their own success is a function of how well the team does under their leadership. And leaders above them look for that kind of humility, that kind of graciousness, that kind of character: people who bring everyone along with them, not just beat their chest about how great they are.”

Most surprising was how frequently everyone—including the students themselves—talked about “followership.”

Within PAWLA, the chief proselytizer of followership is Jeff Klein, the executive director of the McNulty Leadership Program and a lecturer in Wharton and the School for Social Policy and Practice. Part of his classroom-based PAWLA programming, he told me, was informed by surveying coaches, captains, and underclassmen about how each group perceived the expectations of the others.

“One thing we found was that freshmen had an idea that they were supposed to put their head down and stay quiet, and follow directions,” Klein recalled. “But what we were hearing from coaches and team leaders is: We want your voices, we want you pushing the more senior athletes in practice, we want you engaging with them in the locker room, and we don’t want you hanging back passively.

“So when we talk about followership, we’re trying to share research by Robert Kelley and others that in organizational life, the best followers are the ones that show initiative and contribute their own independent critical thinking,” he explained, citing a Carnegie Mellon management professor who jumpstarted academic interest in followership with an influential 1988 Harvard Business Review article. “And those are the folks who really move the needle when we talk about performance within teams, when we talk about change efforts,” Klein said. “It’s a way of reminding every student and every teammate that they can contribute—regardless of where they are from a seniority perspective or a playing-time perspective. And they can be using that athletic experience to grow their own skills as a leader.”

Ventures like the junior-year excursion partly aim to shift participants away from thinking about leadership in hierarchical terms and toward a more expansive conception, said Klein. “We try to create situations where students can extend what’s happening in the classroom and really test their ability to display emotional intelligence, to communicate effectively, or influence people that they don’t have authority over.”

Among the several students who brought up PAWLA’s followership module unprompted, Grace Fujinaga spoke most articulately about what she gained from it—perhaps because she was the only walk-on member of the women’s lacrosse team in 2019–20. The Washington state native’s most vivid memory of scaling collegiate lacrosse’s learning curve was “failing every day” on the way to a seemingly permanent spot on the bench.

“That was hard getting used to,” she recalled. “I didn’t make that transition very well … I was super inconsistent. At the end of the year Karin said, ‘You know, you’d have one good day and then three really bad days, so we just never felt we could put you on the field.’ And that was pretty fair.”

Yet even so, she had an epiphany in a lecture where Klein screened a video depicting a lone dancer at a music festival, gyrating with a crazy fervor that drew snooty gawks from all directions—until one person followed his lead, and then another and another, until hundreds of people were suddenly dancing.

“They talk really specifically about the first person who joined in,” Fujinaga said. “Learning about followership as a freshman, it made me feel like I was contributing to the team,” she told me. “Not as much playing-wise—but as a member who was going to push people, who was going to ask good questions about why we were doing things. Not following blindly but buying into the system—and that’s what was giving our team leaders the platform to do what they wanted to do.”

After the two scuttled COVID seasons, Fujinaga emerged as one of only five players to start all 15 games in 2022. But now the challenge has shifted from tangible benchmarks of individual improvement to the subtler business of diagnosing and addressing deficiencies in team performance. Last season, in which the Quakers went 6–9 overall and 3–4 in Ivy play, was not successful. “And when we talked about why, it came down to accountability—and at the end of the day, approaching conflict,” she said, singling out the need for better reactions to critical feedback, and hence a more skillful delivery of it. This spring she expects to be part of the senior cohort charged with setting the tone, whether she’s a titular captain or not. “It’s a huge responsibility to make sure that things are going right, and that people are getting what needs to be done done … and it’s on all the seniors. At a certain point captains might play a very specific leadership role,” she said. “But who’s going to be the first follower among the senior class? Who are people going to look to, to hop on the train first and show everybody else how to buy in?”

As rain lashed the meadow beneath Shawangunk Ridge, this year’s junior cohort began to pivot in that direction.

After a freshman-year focus on followership and a sophomore year that’s heavy on building self-awareness and insight into different personality types through the use of psychological questionnaires, PAWLA’s juniors turn toward group dynamics and more recognizable mentorship and leadership skills. (Teams participating in PAWLA make it mandatory for freshmen, optional for sophomores, and require juniors to apply for a limited number of spots geared toward developing aspiring captains.) As the downpour tapered into a light rain, they launched into a contest that showed how much room for improvement they had.

The first part of it involved erecting tents. First Ritchie explained the components, from bottom to top: the ground cloth, the “innie” that forms the sleeping chamber, the skeleton that holds it up, and finally the “outie”—a rainfly that shelters everything below it. Then the students raced off to find suitable sites for the spectacle that ensued.

Caught between time pressure and the novelty of the task, three out of the four groups blundered their way into bizarre procedures. One team laid their innie perpendicular to the ground cloth—whereupon a gymnast crawled inside the limp fabric, flailing her limbs around as though unpredictable motions would somehow make it easier for others to affix it to the exoskeleton. Half of another team held their rainfly taut in midair, heeding one of Ritchie’s tips for keeping the tent-construction zone dry … even though the rain had stopped falling. Meanwhile, a third team stood in mute paralysis after layering their “outie” underneath their “innie” and wondering what came next.

Surely no one can be expected to pop up an unfamiliar tent flawlessly on the first try. Yet given these particular false starts—and the Ivy League minds making them—it sure seemed like novelty was less to blame than the simple reluctance of any one person to step up and point out a glaring misstep.

The competition’s second phase (which I will not spoil for future cohorts by divulging) ramped up the need for coordination, communication, and ideally the formal assignment of roles—but proceeded with levels of rhyme and reason that each team later deemed wanting. They passed these self-judgments in “after-action reviews” modeled on US military debriefings.

Indeed, both this preliminary challenge and the next day’s mission had something of a military flavor, reflecting not only Roy’s Special Forces background but WLV’s foundational DNA. It dates back to the late 1990s, when Michael Useem, the William and Jacalyn Egan Professor of Management who is now faculty director of the McNulty Leadership Program, was teaching an MBA cohort that happened to include a West Point graduate and two former US Marine F-18 pilots. Classroom instruction, he felt, worked well for many subjects, “but for leadership comes up short on the issue of moving ideas into action, theory into behavior.” So he had experimented with taking students to Gettysburg, where they engaged in role-playing exercises and analysis keyed to the pivotal Civil War battle. The three veterans in his class urged him to check out the Officer Candidate School at Quantico.

Useem took four MBA students to the base and was blown away. Working as a five-person “fire team,” they faced a series of intricately structured challenges that each required the designation of a leader. “So if I’m designated as team leader, I have to be very good at listening to my teammates, then weave the five of us together under enormous time pressure, to solve a seemingly impossible problem,” Useem recalled. “Typically, on the first few attempts the teams fail—so then the Marine officer will tell you how you messed up.” The feedback could be deceptively simple, from the body language of “the way you stood” to a hard-charging tendency to dismiss ideas without giving them a fair hearing. “And it was amazing,” he said: “As we went to the next station, and then the next after that, tangibly we as a team of five became better at making tough, hard-to-reach decisions under enormous time pressure.”

A quarter-century on, Wharton continues to offer MBA students intensive two-day programs at Quantico. Useem, who is also an avid mountaineer, adapted some of the underlying concepts for use in weeklong expeditions in places ranging from the Chilean Andes to New Zealand’s Southern Alps. It was participating in one of these that sold wrestling coach Roger Reina C’84 WEv’05 on the potential of adapting the model for undergraduate student-athletes. Reina liked how every day, two MBA candidates would be thrust into leadership roles with wide latitude (backstopped by expert guides to ensure no one fell into a crevasse) to determine camp locations, summit-attempt timetables, and the like. “And they could do it any way they wanted—by vote, dictatorship, whatever they chose … then at the end of the day they would get peer feedback,” Reina recalled. The combination of “really experienced facilitators in leadership development” and the “peer-to-peer feedback loop” created “incredibly visceral experiences” that seemed to transform the way every participant, himself included, thought about leading groups.

That combination was conspicuous out on the meadow, where the facilitators used virtually every interaction as a teachable moment. When it came time for Ritchie to introduce himself to the group, for instance, he strode into the big circle and reeled off a 30-second spiel in practiced but unpolished Maori—a familiar ritual in New Zealand that drew some puzzled looks here. Zak Shaw quickly used it to make a point about building trust within a group.

“Role modeling is a key leadership behavior,” he observed, slipping from good-humored affability into didacticism for the first of many times. “Dave role-modeled something which I think is essential to team development and culture within a team,” he continued, “and that is being brave, being vulnerable, and stepping into the space where you feel a bit socially nervous. I would argue that you won’t quite get the result you’re looking for if you’re not prepared to do that. It’s really key that you lean in, step into the space, and make yourself vulnerable.”

Later, facilitating a smaller group, Shaw deployed a tactic meant not to diffuse tension but to harness it. After failing to coax adequate reflection from his clutch of students in response to a query, Shaw posed it again and fell quiet, inviting another spell of silence to hang in the air just a little too long for comfort, before someone finally broke it. “Did you notice what I just did?” he asked soon after. If these juniors found themselves facilitating a group of clammed-up freshmen, he suggested, a purposefully awkward silence might be one way to untie their tongues.

So it continued all afternoon and evening, often emphasizing the arts of feedback: how to solicit it, how to articulate it, how to receive it. By the end of the after-action reviews, the cycle was in full swing—producing more than a few pained faces, at least in the group I was observing. It can be a little overwhelming, after all, to endure immediate critical feedback about the way you’ve just attempted to couch critical feedback.

But this was a crash course in the decision-making, coordination, and communication skills each team would need the next day. Their mission: navigate a series of backwoods trails—some better marked than others, and incompletely represented on the contour map—to locate a “precious cargo” (of who knew what size, shape, fragility, or tractability) to be ferried over rugged terrain, unscathed, to a delivery point. This was paired with an “intelligence gathering” task at once dead-simple and devilish, in that it freighted every step of the journey with a cognitive burden that could be shared but never escaped.

It was in one sense an artificial endeavor. “When I was in Special Operations, our objectives were people,” Roy told them. “But we have a saying in the military: We don’t rise to the occasion; we fall back on our training.”

Sophie Davis and Aly Feeley rose shortly before sunrise along with their teammates, gymnast Kiersten Belkoff, softball catcher Jill Kuntze, and wrestler Lukas Richie. They struck their tents; scarfed down a distressingly caffeine-free breakfast; filled backpacks with water, snacks, and a coil of climbing rope they’d won in a challenge the day before; and hit the trail in sneakers still wet from yesterday’s rain.

In the wake of the previous day’s muddled lines of responsibility, they’d divvied up roles of their own devising. Lukas and Aly would navigate. Kiersten would monitor everyone’s hunger, thirst, and physical well-being. Sophie didn’t want to be the team’s formal leader but was happy to serve as “team mom.” Actually no one had displayed eagerness to be designated the titular leader, until Jill relieved the social discomfort by stepping up to the plate.

I’m not going to say anything about the “precious cargo,” other than that I was happy enough to be its witness rather than its steward. For me, this was an invigorating ramble through a landscape that inspired painter Thomas Cole to launch the United States’ first major art movement in the early 1800s. Likewise, the “intelligence” the team was charged with gathering is not for me to describe. That’s partly because this excursion has become an annual ritual that depends on an element of surprise—but also because the team’s mission was ultimately theirs alone, and it was only through firsthand experience that they could gain anything from it.

There was, however, one particularly interesting passage on the way to their quarry: a literal passage, between stone walls that closed in around what looked like a narrow cave except for a hint of sunlight at the end of the darkened corridor. Having followed red trail blaze markers into this labyrinth of glaciated quartzite, the team pressed deeper in. Aly, fortuitously, had neglected to turn in her headlamp from the night before. Out it came. “Hey, I bet this is where we can use that rope!” somebody else exclaimed, spurring the group forward on all fours.

A few minutes of delicate maneuvering—“Watch out for that overhang” … “Put your foot there” … “Do you need light?”—delivered us into a steep-sided chamber piled with untrodden leaf litter. Another couple minutes of deliberation ended in a quick-and-dirty poll: point in the direction you think we should go. Every finger agreed: onward and upward, though quite how was hard to fathom.

Now Roy pivoted away from quiet observation. “Anybody see a red blaze?” he asked. No. “When’s the last time anybody saw one?” On the other side of the tortuous passageway they’d half-crawled through.

“Wait,” somebody groaned, “Does that mean we have to go back?”

Roy shrugged his shoulders and let the scene play out a little longer, then swooped in with some didactic reflections: about groupthink, and the common bias favoring forward motion, and the sunk-cost fallacy.

It’s one thing to encounter those concepts in a classroom, and another to confront them in an unfamiliar setting, having to manage the emotions of a group, under pressure to achieve a goal within a limited time frame.

“I’ve had teams of executives get to this spot and argue for 20 minutes about every option except retracing their steps,” he said, “even though that’s the only way you can get out of here.”

In the moment—and after retreating to discover that the team had veered off course partly because of an easy-to-miss turn into an even darker crevice—I marveled at the cleverness with which the WLV team had planned this route. But it turned out that none of the other teams made the same mistake. (Perhaps they’d created more space for dissenting voices to pipe up at tricky junctures. PAWLA students, Roy remarked, don’t typically veer into this particular dead end—although executives charge into it all the time.) This is what makes the wilderness a powerful learning platform. “You don’t actually have to make it contrived, or throw a lot of wrenches in,” Roy told me, “because an environment like that already contains a lot of ambiguity.”

Not to mention strangeness, difficulty, frustration, and exhilaration—especially for young people who’ve rarely set foot in a forest or boulder field. Lacrosse defender Vanessa Ewing may at no point have found herself dangling upside-down from a cliff edge attempting dangerous contact with a rescue aircraft, but she nevertheless called the excursion “the most dramatic thing I’ve ever done.” Post-trip survey responses frequently echoed that feeling of challenging novelty.

Refining their approach as they went along, my adoptive team found their precious cargo and managed to deliver it intact. They weren’t the fastest (nor the slowest), and they probably didn’t hit on the optimal strategy, compared to one or two other groups. But they functioned better than they had the day before, and when they hit their stride they shared common burdens with fluidity and even grace. Fatigue frayed their coordination toward the sweaty end, predictably. But even then, in one of the final pushes, I looked up to find Kiersten Belkoff reaching back to pass my own backpack forward through an especially tight spot.

And as exhausted as they were, they conducted their after-action review with considerably more facility than the previous day’s awkward iteration. Again: not perfect, but better. Roger Reina might have taken some satisfaction from watching his 133/141-pound wrestler Lukas Richie grow into the group.

“One of the key things I would like to see him come out of this weekend with—and I think he will—will be more confidence in finding his voice in group environments,” Reina told me. “He’s rounding the corner. I think he’s a great example of someone who can benefit from this program. I think he’s going to be exceptional in the field he wants to go into, which is medicine. And I think by developing his leadership skills and finding his voice in different environments, he’s going to be that much more impactful.”

Which goes back to what motivated Dave Pottruck to begin with: the fact that very few Ivy League athletes aspire to careers in sports. They put in the effort because varsity competition is “a vehicle to express yourself as a human being—to show commitment, to show energy, to show hard work and perseverance: all of these wonderful social and emotional skills we talk to children about today.” But the ones destined to make a mark will do so in realms as foreign to them now as any forest.

“This is going to sound really idealistic,” Anne Greenhalgh told me, “but I really hope that what PAWLA does is give them the opportunity to stop, pause, and reflect on their experience. They don’t need us to reflect. But I think we provide some scaffolding that gives them the occasion to reflect. And if they’re able to think deeply about themselves and their interpersonal relationships, and the way in which they work in a group and make a group work, they have the opportunity to contribute in the future—whether it’s in the context of family or community or the workplace—and make the most of the wisdom they’ve gleaned through the experience.

“We are about doing,” she added. “But I’m going to land on the being: who they are as people. My hope is they’ll be better equipped to make a positive contribution in their own lives and lives of others.”

About a month after the Shawangunk excursion I caught up with the juniors one evening in Steinberg-Dietrich Hall, just in time to witness an overwhelming wave of freshmen pour into a large lecture room, trailing the odor of football pads and weight room sweat. The juniors were there to meet the new student-athletes they’d be mentoring for the coming year, and to begin that process by helping their mentees set formal goals. By the time PAWLA’s directors had finished introducing the program, three things were immediately clear: the underclassmen were restless, ready for the day to end, and way outnumbered their elders. I would not have wanted to be given charge of any of them.

Yet within the space of a few minutes, there was Aly Feeley addressing a dozen strapping football players. “It’s important to set goals,” she was saying, “but before you can do that, you have to step back and ask yourselves a bigger question about your life: What do you want? So go ahead and flip over your sheets of paper…” she continued, and by and by she and Vanessa Ewing were moving from one guy to another—attention firmly under command—coaxing them to refine their first goals of the semester.

I’d been more anxious, however, on behalf of Sophie Davis—who along with two partners had been saddled with the men’s lacrosse cohort, who’d hammed it up with insouciant bids for each another’s attention in a rear corner of the lecture hall while PAWLA’s adult leaders spoke.

Davis was upbeat but matter of fact when I asked her about her assignment: “I don’t think they’re going to listen to me.”

But there was a reason she’d been chosen. I watched it as she led her freshmen through Steinberg-Dietrich’s lobby to a smaller classroom. Following her through the door, the boys made a beeline for the furthest row from the lectern. “Hey, no back row!” Davis exclaimed, firmly but with an invitingly bemused smile. “Come on, guys!”

With scarcely a word, the underclassmen filled the front row and the one behind it.

She was off to a good start.