Cinema studies is a new major program at Penn, but the University’s involvement with the form goes back to Eadweard Muybridge and the earliest days of moving pictures.

By Susan Frith | Photography by Candace diCarlo

The job offer was still fresh in the spring of 2003 when Dr. Timothy Corrigan saw a couple of emails sitting in his in-box. Both were from Penn students. Having heard that Corrigan, then teaching at Temple University, might become director of a cinema-studies program at Penn, sophomores Wesley Barrow and Josh Gorin were eager to meet with him. Each had prepared a pitch about what a new undergraduate major in this field should look like.

“You don’t expect undergraduates to be in touch with you at that point,” Corrigan recalls with a laugh. “It was a nice surprise.”

The students were more than ready for a cinema-studies major, he notes. “It just needed some organization and someone to galvanize it a bit.”

Despite an early brush with film history—when photographer Eadweard Muybridge performed his famous human- and animal-locomotion studies at the University 120 years ago—cinema studies has taken a long time to make it to Penn’s big screen.

The College of Arts and Sciences introduced a film-studies minor in 1999 and cinema has played cameo roles in Penn’s curriculum since the 1960s, but until now there has never been a core group of faculty committed to teaching it.

Listed at the top of the marquee is Tim Corrigan, professor of English and cinema studies, who has taught at Temple, the University of Amsterdam, the University of Iowa, and campuses in Tokyo, Rome, Paris, and London. His research focuses on modern American and international cinema, and his books include A Cinema Without Walls: Movies and Culture after Vietnam; New German Film: The Displaced Image; Film and Literature: An Introduction and Reader; and A Short Guide to Writing About Film.

Last fall Corrigan sat at a table outside Cosí, a coffee bar and gathering place on University Square, giving his plot summary for the new major: It will stretch across the disciplines and collaborate “in as many directions as possible”—with the college houses, the Philadelphia Film Festival, The Bridge Cinema de Lux, and International House, to name a few—to build upon a burgeoning local film culture. Alumni in the film and television industries will help shape and bring visibility to the program, donating their time as speakers and offering summer internships.

“I want high-school students who are sitting around saying, ‘I want to study cinema’ [to be told,] ‘Penn would be the place you’d go … because of the quality of the courses, because of the other students, and because it is really a dynamic, intellectual place for the movies,’” Corrigan says.

With its focus on film history and theory, cinema studies at Penn is not a program designed to teach budding M. Night Shyamalans how to operate a movie camera. (Some film-production classes are available through the fine-arts department, however.) “I’m not so concerned about training the next generation of filmmakers,” Corrigan says, though he guesses “there will be plenty of Penn grads who will end up working in the business in one capacity or another. I think of this major in the broadest of terms—that it’s a really exciting major because we’re talking about what is at the center, for better or worse, of most people’s lives, that is the media, visual technology, and how it communicates ideas, perspectives, opinions. And I think that presence is true, whatever profession they go into. Whether they end up being attorneys … CEOs … educators … knowing what the media is about and knowing what visual technology is about is going to figure into their lives really importantly.”

The year is 1903. The setting, a Doric temple swiftly erected on Penn’s campus. Cameras are about to roll.

Sophomore and would-be-poet Ezra Pound C1905 G1906 is costumed in flowing dress along with the other Greek maidens in the cast of Iphigenia Among the Taurians. Following the production’s resounding success at the Academy of Music, the play’s business manager and the Gazette’s founding editor, George Nitzsche L1898, has convinced the Lubin film company to shoot it for a moving picture.

Enter Professor William Lamberton, of the Department of Greek. (Looking aghast.)

Lamberton: “Do you mean to take moving pictures of this beautiful production and have it hawked around ‘Nickelodeons’ in all parts of the country?”

Nitzsche: It would be “a splendid opportunity … of perpetuating a most notable … production.”

Lamberton: “Well you’ll take it over my dead body.”

One can hear the sighs of the Greek chorus as Penn misses its chance to host the first film with a plot made in America—an honor that went instead to The Great Train Robbery.

In some ways the scene above—described by former Penn English professor Emily Mitchell Wallace in Ezra Pound & William Carlos Williams: The University of Pennsylvania Conference Papers, edited by Dr. Daniel Hoffman, the Felix Schelling Professor Emeritus of English—symbolizes Penn’s past reluctance to embrace the medium that it helped to launch.

But the current buzz of film-related activity on campus and the 28 courses cross-listed with cinema studies this semester suggest that the University has come around. According to Nicola Gentili, associate director of the cinema-studies program, that’s nearly double the number offered last spring. Among the selections: “Screenwriting Workshop,” “The Road Movie,” “Copyright and Culture,” “Film and Art of the Russian Revolution,” “Japanese Cinema,” and “Fate and Chance in Literature and Film.”

“I think we all recognized that cinema is the great art of the 21st century and our students are increasingly in need of an education in visual literacy,” says Dr. Rebecca Bushnell, a professor of English who was recently named dean of the School of Arts and Sciences after serving as dean of the College for two years. “And we had students passionately interested in this field.”

The program has been “in the making for a long time,” she notes. For years film courses have been scattered across the University—at the Annenberg School for Communication, at the School of Design, and at SAS in English, Romance languages, Asian and Middle Eastern studies, and art history.

“About seven or eight years ago, the faculty came together to lobby for the development of a more coherent program,” Bushnell recounts. “So we spent some time searching to get the right people.”

In addition to Corrigan, two new members of the faculty have core responsibilities in cinema studies: Dr. Peter Decherney, assistant professor of cinema studies and English, and Dr. Karen Beckman, the Elliot and Roslyn Jaffe Assistant Professor in the History of Art department.

Beyond the classroom, the program organizers arranged a full slate of events last fall, from a screening at The Bridge by filmmaker Nathaniel Kahn of My Architect (the documentary about his father, architect Louis Kahn Ar’24 Hon’71) and a panel discussion on “Film after 9/11” at Kelly Writers House to colloquia on “Feminist Film Theory in the 21st Century” and “The Digital Cinema Revolution.”

In March Mary Sweeney, a film producer and writer who works with David Lynch, will present his films Mulholland Drive and The Straight Story in an event cosponsored with The Penn Humanities Forum. Cinema studies is working with the Philadelphia Film Festival to have more of the festival’s films shown in West Philadelphia and to boost faculty and student participation in the annual April event.

“We used to have only three or four film showings [around campus] a month,” says cinema-studies major Wesley Barrow, noting how Penn’s film culture has grown. “Now every week there are probably three or four. It’s getting a lot bigger.”

In the fall the cinema-studies program will host a conference that celebrates Penn’s film pioneers, including Eadweard Muybridge, documentarian Sol Worth, and avant-garde cinema promoter Amos Vogel as well as alumni who currently work in the industry.

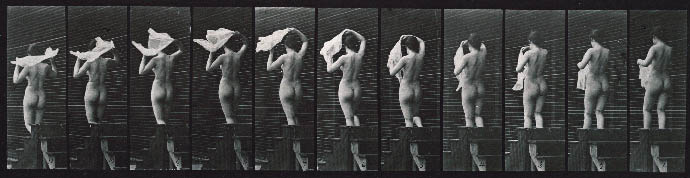

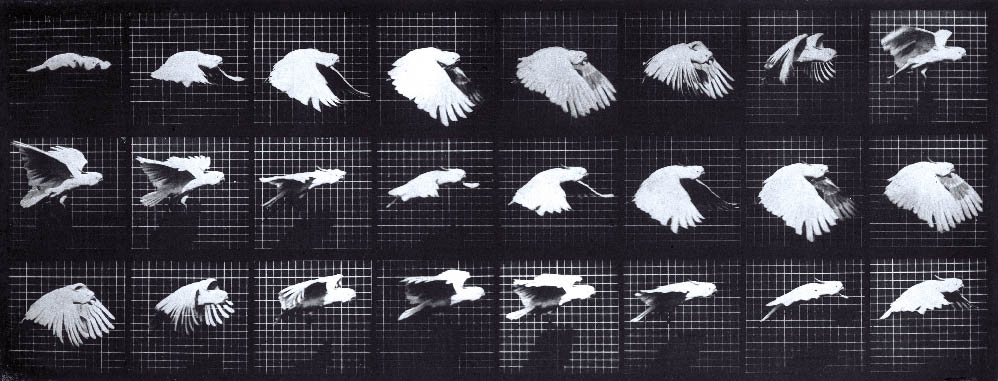

With a fishing pole slung over one shoulder, the woman steps gingerly from stone to stone, as if trying to keep her ankles dry while crossing an imaginary stream. She wears only a long braid down her back, but seems unaware of the gaze of three-dozen cameras around her and the fact that her split-second movements will become a part of history.

One of the photographic subjects in Eadweard Muybridge’s animal-locomotion studies at Penn, she joins a kinetic troupe of Philadelphia zoo animals, Penn student athletes, hospital patients, and art models who charge, pole-vault, limp, and waltz from one frame to the next.

We see them now in books and in special collections like those found at the University Archives and Records Center. But if you were in the audience for one of Muybridge’s American and European lectures more than a century ago, you would have been dazzled by a flickering series of images projected by the zoopraxiscope he invented.

“Muybridge’s work is generally considered one of the great watershed moments in terms of the transition from still photography to film as we know it,” Corrigan says.

University Archives and Records Center

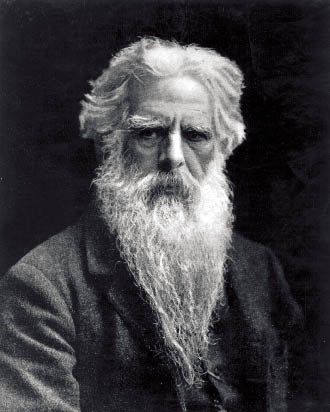

An English-born photographer with a white cataract of a beard, a curiously spelled name, and a mixed reputation, Eadweard Muybridge arrived on campus in 1884 at the invitation of Provost William Pepper C1862 M1864 and several Penn benefactors. He was reportedly given a $5,000 advance “for the prosecution of his work on the investigation of animal motion.” (Among those appointed to a commission to supervise him was the American realist painter Thomas Eakins.)

Muybridge had achieved fame in California several years earlier by proving with his instantaneous photography that when a horse gallops, at some point all four hooves leave the ground. Working on the property of Penn’s veterinary hospital, Muybridge set out to improve his techniques. He created an outdoor photo studio that consisted of a 120-foot-long track laid out along a black-painted shed, with banks of cameras set up to capture a subject’s every movement at three different angles. Their shutters were released automatically with electro-exposing devices.

Though he was known as an entertaining speaker, Muybridge’s colleagues at Penn weren’t always sure what to make of the man, according to Gordon Hendricks, author of Eadweard Muybridge: The Father of the Motion Picture.

For one thing, there was his fondness at lunchtime for maggoty cheeses bought on South Street. Then there was the matter of his unkempt appearance. Pulling Muybridge aside one day, Provost Pepper advised that he dress in a manner befitting his association with the University. “‘Take for example your hat; it has a large hole in it through which your hair is protruding,’” the provost pointed out. “Muybridge then looked at his hat and observed, as if for the first time, ‘Why it does have a hole in it.’”

Edward T. Reichert, a physiologist who helped Muybridge in at least one odd experiment—photographing the exposed, beating heart of a snapping turtle—described him as “the most eccentric man I ever knew intimately” and “very much a recluse.”

A fact that probably didn’t escape people’s attention was Muybridge’s previous legal troubles in California. Ten years earlier, his wife, Flora, was “on terms of criminal intimacy” with one Major Harry Larkyns, in the words of The Calistoga Free Press. Upon learning of her infidelity—as well as the true parentage of his infant son—Muybridge tracked down Larkyns at the Yellow Jacket Mine in Calistoga, permanently ending his rival’s cribbage game with a Smith & Wesson. A jury acquitted him of murder.

The problems Muybridge faced at Penn were mainly of a logistical nature. One was trying to secure permission to photograph “interesting cases” from Blockley Hospital for the Poor to illustrate abnormal locomotion. After initially rejecting his idea, the hospital’s board of guardians eventually consented and provided 23 models for the project, according to Hendricks. Supplementing that body of work was a “normal” model who voluntarily submitted to having artificially induced convulsions for the cameras.

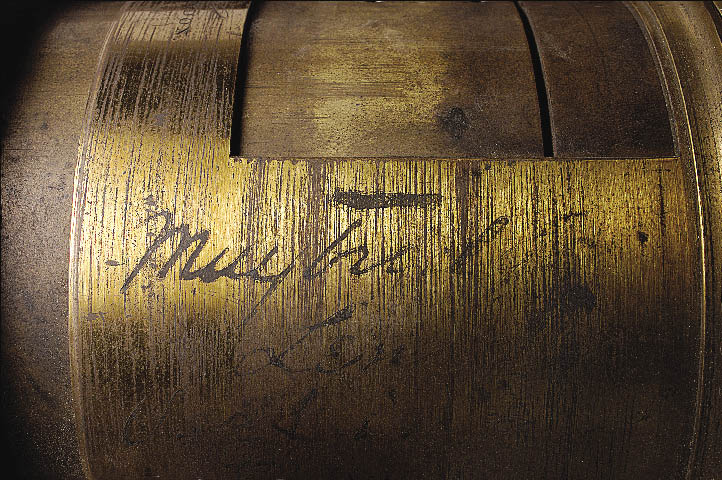

Thousands of photographs and $40,000 in expenses later, there were 781 plates ready for publication. Muybridge presided over his own prospectus and catalogue in a front room at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, helping subscribers choose and order 100-plate sets at a cost of $100.

Though Muybridge’s work made no money for Penn, his images impressed audiences from Turin to Oxford to Munich. “Had Muybridge exhibited his Zoopraxiscope three hundred years ago, he would have been burned as a wizard,” wrote George Augustus Sala in the Illustrated London News.

“So perfect was the synthesis [of Muybridge’s images] that a dog in the lecture room barked and endeavored to chase the phantom horses as they galloped across the screen,” the Berkeley Weekly News reported.

A set of photographs was even sent to the Sultan of Turkey, in the words of The Pennsylvanian student newspaper, “to soften his heart to the University and incline him to give her scholars permission to carry away with them what may be left of Babylon and surrounding country … ” A thank-you note in the Penn archives from the Premier Secretary of the Sultan graciously acknowledges the gift’s receipt.

The pictures were identified in Muybridge’s catalogue according to the level of undress they featured—fully clothed, nude, semi-nude, pelvis cloth, transparent drapery, draped, and bare feet.

“Care is taken that the nude series cannot be bought by those who do not intend to use such work for serious study,” reassured a March 5, 1888, article in The New York Times, headlined, “Wonders of the Camera.” The article went on to emphasize the scientific and artistic contributions of Muybridge’s work, including the fact that “those who study the photographs of men and animals in locomotion see positions in moving bodies which their eyes always refused to register before.”

“In the early days this kind of work in photography and motion studies was considered primarily a scientific pursuit,” Corrigan says. “There were people who tried to turn it into an amusement, and those became in some ways the twin poles that pressured cinema through even its early stages: Is this just a pastime, an amusement? Or is this a powerful tool for scientific and social investigation? If one wants to be schematic about it, you can sort of look at film history as struggling between those poles ever since.”

For a long time cinema studies was looked upon as a “soft” discipline, according to Corrigan, but “a huge explosion of scholarship and theoretical thinking” in the 1970s and 1980s improved its profile.

Films actually were used very early at some Ivy League universities, including Harvard, Yale, and Columbia, points out Peter Decherney. In his upcoming book, Hollywood and the Culture Elite, Decherney shows that collaborations between higher-education institutions and Hollywood in the 1910s and 1920s promoted an American national identity while conferring legitimacy to the medium of film.

He cites Columbia as one example. “By 1914, a screen in the the journalism school showed films for a wide range of courses from psychology to history to journalism,” Decherney says. A few years later, the first film courses were offered through its art history department. “Film was taught as art for its own sake rather than as an illustration of other subjects.” Columbia’s education division also used film in two ways: for “teaching values to, or ‘Americanizing,’ the children of immigrants” and teaching screenwriting as a vocation.

Even at Penn (despite Professor Lamberton’s obstructions), film was used as a publicity tool early in the 20th century, University Archives records show. Alumni groups around the country could request film reels of such momentous events as Penn’s Commencement and “the Annual Smock Fight between the Sophomore and Junior Classes in Architecture.”

IN the 1960s and ’70s Penn’s Annenberg students took on a more serious cinematic pursuit, learning documentary-making from Sol Worth. It was at Annenberg that the renowned painter and filmmaker developed the concept of the biodocumentary, “using film as a tool through which people, mostly young people, could [present] their world view,” says Dr. Larry Gross, who was the Sol Worth Professor of Communication at Penn before moving to USC’s Annenberg School for Communication in 2003. Gross recalls Worth as a close colleague and mentor.

“It’s important to remember that film technology then was much more cumbersome than it is now, so giving moving cameras to amateurs was not an easy thing to do. Now kids are doing Photoshop on their desktops and creating films—and in a way it’s sad that I can’t see how Sol [who died in 1977] would have responded.”

During his time at Penn, Worth put the same filmmaking tools in the hands of Native Americans living in Pine Springs, Arizona. The Navajo Filmmakers Project, which began in 1966, “was extremely influential because it was the first to do something that had been thought of but never implemented, namely seeing the world through ‘native eyes’ rather than outsider eyes,” Gross says.

“Today the idea that people can speak for themselves and make their own records and make their own voices heard is fairly commonplace, and I think in part this helped stimulate what became a major movement in anthropology—which was thinking of ethnographies as narrative statements rather than as objective science.”

According to Gross, the first “serious move” at Penn to introduce film analysis was a graduate course taught at Annenberg by historian Amos Vogel, whose Cinema 16 film society in New York was a showcase for avant-garde and experimental cinema from 1947 to 1963. Vogel also taught an undergraduate course through the College. (In terms of seriousness, Gross says, it was steps above a film-history course taught in the 1960s in the basement auditorium of the fine-arts building, where it was not unusual to pick up the scent of marijuana wafting across the back of the room.)

Dr. Paul Messaris, now associate dean of the Annenberg School for Communication, served as Vogel’s T.A. for one semester. “The more daring, adventurous, radical a movie was, the more Amos liked it,” he recalls, “and his courses were a dazzling showcase for his kind of movie.” Paul Sharits’ Razor Blades was such an example. “The only way I can describe it is by saying that it leaves the viewer feeling as if his/her eyes have been assaulted with a razor.”

In 1974 Vogel wrote Film as a Subversive Art, a book that Messaris says “reflected his interest in movies that challenge the social and aesthetic conventions of established mass-media cinema.”

Though his classes were popular with students, Vogel’s hiring was controversial, Gross says. “There was a great deal of resistance in the College, mostly in the English department, at that time. The prevailing view in much of the academic world was that film was beneath serious academic attention.”

Dr. Robert Lucid, professor emeritus of English, recalls it a little differently. The resistance to funding cinema studies “has always been about money and there has always been competition for dough from other special programs,” he says. “No part of the University had any money in the 1970s. It was a crisis period financially on every front, and cinema was a new enterprise. Being stone-broke and funding new enterprises are just contradictory ideas.”

Lucid himself recalls the struggle to get a faculty appointment in cinema studies when he became chair of the English department in 1980. “Every year we were told, ‘No way,’ so we started teaching a lot of cinema through part-time people. We did it on the side and on the cheap for a long, long time.”

Rather than simply catching up, however, Penn is “actually on the ground floor of a new wave of film studies in American universities,” predicts Decherney, noting the creation of several new Ph.D. programs in this field around the country. (According to Corrigan, Penn has no plans for a Ph.D. program in cinema studies, but is working on a graduate certificate.)

“Not too many of our peer schools have cinema-studies programs in their schools of arts and sciences and liberal-arts programs,” Rebecca Bushnell adds. “We think we can offer something unique with a cinema-studies program based in a liberal-arts education.”

So far nine students have declared cinema studies as their major (another 20 are minoring in the subject). “I try to balance the desire for it to be popular with the desire for it to be a tough major,” Corrigan says. “People aren’t majoring in this simply because it’s fun, but because they feel it’s going to challenge them and they’re going to learn something by doing this.”

In cinema-studies courses this spring, students will explore, among other topics, the changing shape of the road-movie genre; ethical dilemmas confronted by documentarians; how copyright law has driven art and entertainment; cinema as an instrument for social change in India; how film constructs and reflects attitudes about racial difference; and the use of visual propaganda in the communist cultural revolutions.

“A university without a serious film curriculum and an integrated film curriculum is going to be left behind,” says Jon Avnet C’71, a producer and director whose long list of credits includes Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow and Fried Green Tomatoes. “The reach of the media with all of its tentacles is so ubiquitous that its impact has to be studied by people who are not in the film business—by sociologists and social-science people.”

To give one example of where such analysis is needed, Avnet points to a spate of historically inspired films—Gladiator, Alexander, Nixon, JFK—that provide “ridiculous interpretations of history. I think that has a big impact on people who are watching it. Not everybody gets a rigorous education. You have to counteract what you learn on television or the movies about [historical events].”

Avnet doesn’t have a problem with the lack of a production focus at Penn, noting that “60 minutes by fast train and 90 minutes by a slow one is NYU, a good film program in production. I don’t think Penn should be competing on a production basis. But there are things at Penn that don’t exist anywhere else, and taking advantage of that is smart.”

Marc Platt C’79, another alumnus who knows something about film, agrees. Platt served as president of production at Orion, TriStar, and Universal—helping to bring movies like Philadelphia, Sleepless in Seattle, and Jerry Maguire to the screen—before forming his own studio and producing such hits as Legally Blonde. “When aspiring filmmakers come to me, I say I think it’s best to get a strong liberal-arts education and to learn history and English and all the disciplines that intertwine with the development of making film as well as the history of film and film theory,” Platt says. “The [production training] you can save for graduate school.”

Both Platt and Avnet see the large number of Penn graduates working in the entertainment field as assets for the cinema-studies program.

Avnet believes he can help serve as a liaison between Penn and Hollywood, encouraging alumni—“many of whom are doing quite well out there”— to “bring it back as many ways as we can here.”

Platt believes that alumni who are successful in the film business “become sort of a walking commercial, if you will, for the University. I think there is also a lot the film community can do,” he adds. For his part, Platt tries to hire Penn students for film-production internships.

Corrigan would like to see more internships developed for Penn’s cinema-studies majors, though “academic and intellectual issues should be the centerpieces around which all of these other activities will make more sense and be more valuable.”

As the program grows, he also hopes to develop better connections with other parts of the University, such as the Annenberg School, the Digital Media Design program, and Wharton. For example, he says, “I think it’s really important for our students to get a good sense that [cinema] is a business, and that it’s not just an art and not just an entertainment.”

Putting the concept of academic boundary-crossing into practice, new faculty member Karen Beckman has been teaching a yearlong course in conjunction with the ICA on the use of film and video in the contemporary art museum.

Last fall her students traveled around the country looking for works to include in their own show. This semester they’ll be “learning the range of museum work, doing installations, getting works of art, helping with fundraising and publicity,” she explains. “It’s a tremendous opportunity for exposure to every aspect of the art world and some of the film world.”

For many college students, winter break is a time to see high-school classmates and unwind from exams—and maybe go to the movies. When Josh Gorin travels home to Pittsburgh, he catches up with old friends while making movies.

“It’s a three-week process, from concept to scripting to shooting to production to premiere,” says Gorin, a cinema-studies major whose quickly crafted group effort, Winning Caroline, was named Best Undergraduate Comedy in the Ivy Film Festival last April. “It’s certainly a tight schedule, but a lot of fun.” The College senior was speaking from Los Angeles last November, while on a semester’s leave for an internship in research and development with Walt Disney Imagineering.

One of the first students to contact Corrigan, Gorin was originally a Digital Media Design major, but the extensive course requirements didn’t leave him much time to take liberal-arts classes or focus on his interest in film. “I was looking into starting my own major, so I was happy to hear they were creating an official program [in cinema studies].”

One of the benefits of the major is that, “You’re forced to see lots of movies you normally wouldn’t seek out,” and in the process learn much about storytelling and interpreting “the messages contained in the media,” he says. Students enrolled in cinema-studies courses this spring can partake of a wide range of selections, from Mexican horror movies to adaptations of Jane Austen’s novels to Fellini’s contributions to postwar Italian cinema. Coming attractions include Mike Nichol’s The Graduate, Fritz Lang’s M, Luis Buñuel’s Los olvidados, and Ayub Khan-Din’s East is East.

“After you go to Penn or to any academic institution to study film, you’re not really satisfied going to the theater back home, where all they have is Shrek or Spider Man II or stuff like that,” says Wesley Barrow, a senior cinema-studies major from Houston.

In his spare time Barrow has reorganized a campus student organization called Talking Film, which combines formal events with casual biweekly excursions to the Ritz. The group also runs a listserv that functions as “kind of an open marketplace for kids interested in any aspects of film,” including those working on film projects who are looking for actors or cinematographers.

With 600 students on its mailing list, Talking Film isn’t limited to cinema-studies majors, Barrow says, pointing out that, “Some of the Wharton kids are the biggest film nerds we have.”

Before he even came to Penn, Barrow traveled around the country with a cousin’s band, getting his first taste of the entertainment industry. A highlight of his Penn studies was traveling to the Cannes Film Festival during the summer after his sophomore year for a non-credit course.

Through the film-production classes he has taken here, Barrow found that his talents lie in “picking out what would be more successful rather than making something successful. If I enter the film industry, it would be as an agent or producer,” he says.

Barrow spent last summer working at the William Morris talent agency; after graduation he’s thinking of pursuing one of the coveted jobs in the company mailroom, where some of the most famous names in Hollywood got their start. The minimum-wage assignment is a prerequisite for becoming an agent, he says.

Because the cinema-studies major wasn’t available when he first got to Penn, Barrow is now scrambling to gather the credits he needs to graduate in May. Last semester he was taking three courses in cinema studies, each of which required watching one film a week on top of attending classes.

Now that cinema studies is a reality at Penn, Corrigan is already hearing from high school students interested in pursuing the major. Last fall one of them asked him to watch a film he had made.

“A lot of [student] are already making their own [digital videos] or writing their own scripts.” Though some may dream of becoming the next great filmmaker, Corrigan says, “in general, I think they just find this a really exciting way to express themselves and to engage with the world. [Film] is where they find a lot of their ideas—if not presented, at least provoked.”