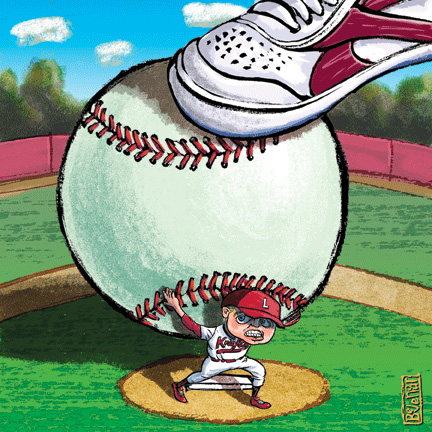

Our adult obsession with youth sports isn’t just unsettling. It’s tradition.

By Mark Hyman

Meet Louis J. Castellano Jr., perhaps the only Little League Baseball coach ever to ask the Supreme Court of New York to save his job.

Castellano coached the Orioles of Hempstead, Long Island. On opening day, one of his star players did not arrive for the game. The team lost. Castellano was peeved. The next time he saw the boy’s grandmother, he gently broached the topic (or vigorously argued the point—this is in dispute). The boy’s mother got angry and demanded that Castellano be fired.

More maneuvering followed. The mother transferred her son to a neighboring Little League. Castellano was accused of cheating when allegations surfaced that he’d suited up his 7-year-old son (players had to be at least 8). Castellano eventually appealed his dismissal to New York’s highest court, which refused to get involved. It must have been an exciting season for the Hempstead Little League, what with lawyers hovering and board members checking their liability coverage.

This sounds like one more sign that misguided adults are taking youth sports way too seriously, and it is. But there’s something different about this particular cautionary tale. It happened 40 years ago.

We tend to regard the shortcomings of youth sports as a modern-day problem—if not created by our generation, then perfected by it. No doubt, we have done our part. Our culture abounds in organized games that are shaped more by adult ambitions than the needs of kid players. My brain is forever imprinted with images of the overheated Illinois father who, in 2008, ensured his 11-year-old-son’s defeat in a wrestling match by leaping onto the mat and attempting to pin his startled opponent. But youth sports dysfunction isn’t new. Nor are the warnings that, for our kids’ sake, we ought to lighten up.

When I started work on a book about the evolution (or devolution) of organized sports for children, I had no illusions about being first to the party. I knew that experts had been saying for years that kids games were becoming too serious and too competitive for the good of the little people in uniform. I was wrong, though—laughably wrong—about how long the warnings had been coming.

I figured they might have begun in the 1970s. That decade was a tipping point for youth sports. The supremacy of play-for-fun neighborhood leagues had begun to slip. Travel ball and elite club teams had gained a toehold. For the first time, it was possible to send your child to a private tutor to learn how to become a lacrosse goalie.

I wasn’t far into my research when I realized how mistaken I was. I was digging into sports specialization, a subject much debated these days on youth sports fields and in pediatricians’ offices. Kids who play and train in the same sport year round are often terrific talents, with skills far more polished than those of past generations who changed sports with the seasons. But there’s a powerful downside. Kid specialists are far more vulnerable to injury than kids whose parents insist on variety, moderation, and breaks from organized sports. If all your 8-year-old does is kick a soccer ball, expect a sore knee one of these days—or perhaps a ruptured anterior cruciate ligament.

I was confident that I would find no discussion of specialization before about 1975. Instead, I came across an impassioned editorial on the topic written during the Hoover administration. “Not only does [premature specialization] deprive the young athlete of the opportunity to brouse [sic] around and find his interests in the various sports and various positions, but it causes him to lose his adaptability,” opined the editor of the Journal of Health and Physical Education in 1932.

That was typical. The deeper I dug, the clearer it became that the issues troubling doctors, psychologists, educators, and ex-pro athletes about youth sports today are eerily similar to those that framed the debate 75 years ago: Youth sports were too competitive. There’s too much pressure. Talented players got all the glory while weaker ones rode the bench, never developing their skills.

In 1952, the National Education Association issued a 46-page booklet titled Desirable Athletic Competition for Children. Inside was a three-year study that read like a double-spaced demolition of youth sports. It panned the entire enterprise, concluding that “highly organized competition, patterned after high school and college sports, gives youngsters an exaggerated idea of the importance of sports and may even be harmful to them.” The report urged leagues to do away with “high pressure elements” in their programs, including all-star teams and media accounts of games that included “individualized publicity about good players.” It recommended a total ban on tackle football for children not yet in the ninth grade. In short, the NEA seemed to be telling the organizers of Pop Warner, Little League Baseball, and other leagues to pack up their equipment and go home.

The medical establishment was nearly as outspoken. In June 1958, attendees at the American Medical Association’s annual meeting in San Francisco heard a rebuke of all “highly organized sports for children.” Dr. Fred V. Hein, an AMA official, told the group that structured sports leagues “shut out” boys who were not physically gifted, and girls of all abilities. The system of catering to the most talented players “helps to perpetuate physical unfitness among the rest of children,” he said.

Perhaps the harshest critic of youth sports in the last 50 years has been Joey Jay. For years, Little League Baseball pointed to Jay for validation. As the first Little Leaguer to graduate to the major leagues in 1953, Jay was living proof that the organization had, in a sense, arrived. Its former players were now grown men contributing to society and, in Jay’s case, pitching the Cincinnati Reds to the 1961 National League pennant. Yet when Jay signed up his 7-year-old son to play in a Cincinnati Little League in 1965, he was surprised to find neither his wife nor child happy. “My wife kept complaining that Stephan was coming home tense and exhausted. I went to one game and watched angrily while the coach made a tired 6-year-old who just couldn’t get the ball over the plate, go back to the mound and keep pitching until he was ready to collapse,” Jay recalled.

Jay wasn’t just angry about his son’s experience. In 1966, he wrote an article for True magazine titled “Don’t Trap Your Son in Little League Madness,” decrying the state of Little League Baseball everywhere. It was part commentary, part diatribe. Jay challenged the qualifications of coaches and the motives of parents. He questioned the health effects of Little League on young bodies. As Jay saw it, kids were far better off learning and enjoying sports on their own than being under the thumb of adult minders. “What happens today is that many Little Leaguers are burned out before maturity. I think this explains why Little League has had such limited impact on baseball, why it has failed to produce a gold mine of talent not only for the majors but for high schools and colleges as well. The fault lies in its concentration on immediate victories and premature glory, rather than on teaching basic skills and sound development … Championships seem to come first, the youngsters last.”

Who was responsible? Jay called out “idiotic fathers” who made being the star of a Little League squad “a new status symbol not far below a Cadillac convertible.” Mothers were similarly chastised for being caught up in the “Little Leaguer status race.” Jay (or more likely, his co-author Lawrence Lader) wrote: “I saw one mother shout at her boy as he left the field after an error, ‘Don’t embarrass me again before everyone!’ Mothers from opposing teams often trade insults in the stands over their sons’ prowess. Neighbors end up feuding with each other … In their mania for victory, adults can wreck the whole concept of sportsmanship.”

Jay was appalled by “how many coaches are frustrated athletes, hell-bent on producing winning teams to recreate their own dreams of vanished glory. Many fathers take over their teams and consciously or subconsciously push their sons’ careers. Their driving ambition has produced a new medical ailment, “Little League elbow.”

In the years since, not much has changed. Youth sports keep getting bigger and more serious. Thanks to ESPN, we now have a nationally televised high school basketball tournament modeled after the NCAA Final Four. Why haven’t adults objected? Simple answer, I’d say. We have too much invested in the status quo. I have my hand up, too. It’s fun to watch your kid score goals and swish baskets at the buzzer. And it’s irresistible to wonder whether your son might really be that one in a million to play quarterback at Stanford, or whether your daughter could someday cross the finish line ahead of the pack at the Penn Relays.

As Bob Bigelow C’75 [“Bob Bigelow’s Full Court Press,” May|June 2002], a former Penn basketball star and NBA player who now advocates for a more kid-centric approach to youth sports, puts it: “Adults want to win. Kids? They just want to play.”

Carl Stotz might have seconded that. A onetime bookkeeper and Venetian blind salesman, Stotz invented Little League Baseball in 1939. He drafted the rules, helped build the first Little League diamond, and coached one of the first teams in the central Pennsylvania burg of Williamsport. He remained at the helm of Little League until 1956, when he was ousted in a power struggle with a corporate sponsor.

Stotz never attended another Little League game. He became an especially sharp critic of the Little League World Series, the iconic youth sports spectacle held every August. He faulted it as being too intense for youth players. “I became utterly disgusted,” he explained. “Originally, I had envisioned baseball for youngsters strictly on the local level without national playoffs and World Series and all that stuff.”

Funny thing is, Stotz said that in 1964.

Mark Hyman C’78 is the author of Until It Hurts: America’s Obsession with Youth Sports and How It Harms Our Kids (Beacon Press, 2009; www.untilithurts.com).