The Mourning of Mario Lanza, Chubby Checker’s twisting rise and fall, a race riot in North Philadelphia and the Phillies’ 1964 “nervous breakdown.” Memories of a boyhood in the city.

By Gerald Early |Photos from Temple University Urban Archives

In the fall of 1955, my mother became a school crossing guard for the St. Mary Magdalene di Pazzi Catholic School, located on the northeast corner of Seventh and Christian streets in South Philadelphia. My father died in early 1953, when I was about nine months old, and since his death, my mother had been doing work of one sort or another, none of which she found satisfactory. She then went on welfare. Her options were few, as she had not finished high school and could not take a job that would keep her from her children all day or all night. (At the time, my oldest sister was nearly six years old and just starting school.) She did not like being on welfare and desperately searched for another job. It took more than six months for her to get the school crossing-guard job. This job was ideal for her situation, because it was part-time but spread out over the day. No particular segment of the day—the morning opening bell, the lunch hour (children were sent home for lunch in those days of truly neighborhood schools), the afternoon dismissal—required more than 90 minutes of her time. In effect, she didn’t need a baby-sitter.

The job had two drawbacks. First, welfare rules at that time required that if she took the job she would have to reimburse the government for the amount of relief she received. Second, the school for which she was to serve as crossing guard was an Italian-Catholic institution that did not admit blacks, or indeed anyone who was not Italian-Catholic. Indeed, her employer, the police department of the city of Philadelphia, was hesitant about placing a black woman at that school and would have preferred having a white woman there. I suppose they could not find one. Both of these conditions gave her momentary pause, but she took the job, anyway. In two years, she paid back the government. She kept the job of guiding Italian-Catholic children over Seventh Street and Christian Street for over 20 years. She was never fully aware of the fact that she was, in her way, a civil rights pioneer. In her own minor way, she broke a significant barrier in race relations.

My mother carried herself with a great deal of dignity; she is very black-skinned and felt she had to. She couldn’t fall back on providing white people the visible comfort of being light-skinned and, thus, from the point of view of the herronvolk, just slightly removed, as it were, from being “one of us,” or at least clearly better than “the rest of them.” Because she wore a uniform—a cap that looked very much like a policeman’s cap, a long, double-breasted blue coat in the winter, a blue jacket, white blouse and gray skirt in milder weather—the Italian kids in the neighborhood called my mother “the lady cop.” The uniform, I think, intensified the dignity my mother brought to the job and made the Italians respect her all the more. As a boy I was certainly proud of her every day I saw her on that corner. She glowed with what I can only call a kind of African nobility transfigured to an American frequency, looking a great deal like her father, who was very black-skinned as well. Surely, the fact that she had the job and was such a success in it had a significant impact on my life. It made it possible for me to grow up among Italian-Catholics, people who under most circumstances loathed African Americans with a passion that took on the grandeur of an artful design. Generally, I liked the Italian-Catholics I lived with very much, even though I knew they were very racist, with the typical resentments and narrow-mindedness of a patriarchal working-class culture that in many ways resembled the black working-class culture that I knew but in some important, vital ways did not. I had learned enough about the Italian-Catholics to know that I did not ever want to be one or to be like one. By the time I was a teenager, I knew I never wanted to be an ethnic.

However racist they were, their racism was never directed at me. It always went around me, and I was indulged in ways that no other blacks in the neighborhood were. I was always a pretty bookish, studious boy, and far from resenting it or feeling threatened by it, the Italians were extremely supportive of my timid intellectual ambitions. “Jerry, you go to school and make something outta yourself. Don’t be like these bums around here. You a smart boy and you can grow up and be a great man,” our Italian landlady, Mrs. Curci, said to me all the time. They all said that to me—the shop owners, the fruit-stand merchants, the parents of the kids my mother crossed, the kids themselves I played stickball and softball with. I don’t mean to say that I did not have some unpleasant moments with the Italians, but they were very few and they did not bother me much, not because I did not take these racist moments seriously but because I had seen them in other guises and understood, or at least could fully sense, the remarkable complexity of their humanity. My life with black people, both then and subsequently, would have been a great deal easier if the racism of the Italian-Catholics had been more directed at me, or if those few unpleasant episodes had been greater in number.

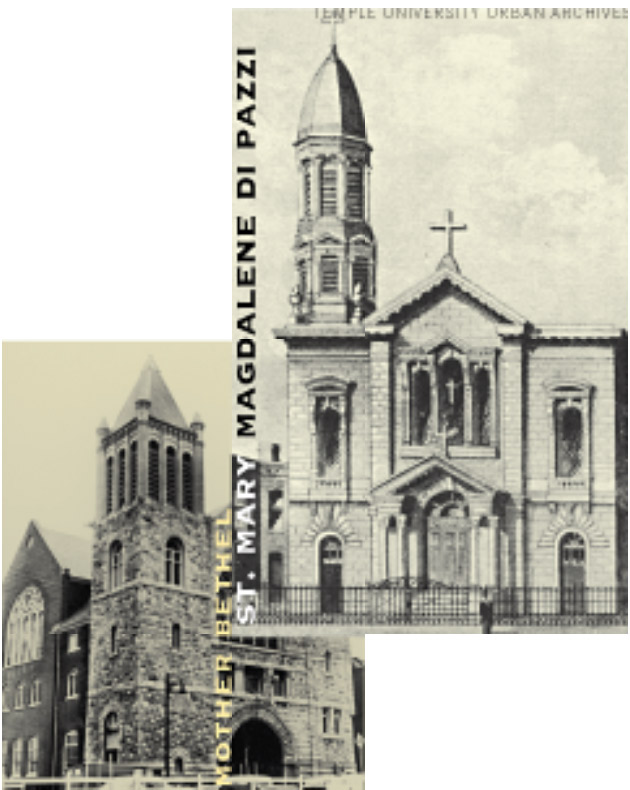

The St. Mary Magdalene di Pazzi Catholic Church is located on Montrose Street, one of the those narrow side-streets that Philadelphia is noted for, midway up the block, between Seventh and Eighth. It was founded in 1852 and is the oldest Catholic church in the city. It still sits, cathedral-like, massively medieval in its institutional glory, among the tiny, neat rowhouses as a kind of bulwark of Little Italy against the disorder and squalor, the heroic and rebellious chaos of the blacks who lived just a few blocks away in their own little rowhouses and in the Southwark Plaza Projects at Fifth and Carpenter streets. For that was the unofficial name of the neighborhood in which I grew up: Little Italy. Ironically, the oldest black church in America, Mother Bethel, founded by Richard Allen, is just six or so blocks from St. Mary’s. It is one of the strange facts of history that black people had actually been living in this ward longer than the Italians. People forget that Du Bois’s 1897 classic book, The Philadelphia Negro, was about the very ward that I lived in, anchored by the Mother Bethel Church.

When I was a boy, old Italian peddlers still delivered milk by horse-drawn carts, and there was still a great deal of Italian spoken among the older residents, although the kids resisted the language mightily and few could speak it, although many understood it. The most famous person who was ever a member of this church—St. Mary Magdalene di Pazzi—and who went to the elementary school where my mother was the crossing guard was a singer named Mario Lanza.

The house where Lanza was born and grew up, 636 Christian Street, is now a historic landmark. For a long time, during my boyhood, whenever I passed the house, in the front window was a huge picture of Lanza with a lighted candle on either side of it. He was born Alfred Cocozza, and I remember whenever I heard his grandfather, or a man I was told was his grandfather but it could have been his father, refer to him, he always called him Freddy. He was willing to talk about Lanza to anyone who was willing to listen, even his black newspaper boy. He told me Lanza was the greatest tenor since Caruso. He claimed he had heard Caruso and that Freddy was better. Who was I to dispute that claim? After all, by the time I was 12 years old and delivering the Philadelphia Inquirer to Lanza’s relatives who were still living in the house, I had seen Lanza’s most celebrated film, The Great Caruso, made in 1951, about three times, and was convinced that he was the greatest singer I had ever heard. He certainly made opera appealing, even sexy, a form of music I would normally not have listened to at all. I loved The Great Caruso and nearly cried at the end when Caruso dies, thinking, probably because I saw the film several years after Lanza died, that it was the story of his life rather than Caruso’s. Emotionally, I was sure that Lanza himself died at the end of the film, although intellectually, I knew better. But it was accepted in the neighborhood that Lanza was the American Caruso. Every Saturday, for many years, at Lanza’s family home, his records would always be playing, sometimes serenading the block. (Some people, naturally, preferred Caruso and played his records, but these were in the minority.) In this way, I associated opera with the Italians I grew up with in much the way I associated them with homemade wine when the block smelled of fermenting grapes every Friday and Saturday. I made this association even though nearly all of the Italian kids I knew hated opera, did not like Mario Lanza, and were ashamed that their parents made wine in their basements. I found all of this a comfort.

Lanza attracted a great deal of attention from the beginning. Everyone who knew opera and those who thought they did thought he had an exceptional voice. What struck many people was its natural, melodramatic quality, its over-emotional sensibility. These very elements struck audiences about Caruso’s voice, with his trademark sighs and cries that became tricks on evenings when he couldn’t feel the music or wasn’t up to performing. In other words, even during his student days, there was something about Lanza as a “natural singer,” as someone wrapped in the quaintness of his ethnicity, that captured the fancy of those around him. This image was to dog him his entire career, particularly as a central part of the criticism that he was not truly an opera singer at all. After all, the criticism went, if he were he would be singing in operas on stage. And there was more than a bit of the barrel-chested machismo of the inner-city ethnic in him. As he confided once to his close friend and personal trainer, Terry Robinson, “It’s all sex, Terry. When I’m singing, I’m scoring. That’s me. It comes right out of my balls.”

He was discovered in the army by Peter Lind Hayes, who was looking for singers for a production the army was putting on for the troops called “On the Beam.” Lanza did concerts for the rest of the war. One might say he sang his way through the conflict, much better than fighting one’s way through. Immediately after the war, he was signed by RCA Red Seal, the prestigious classical label, and eventually became its biggest selling artist by far. In 1947, he became a member of the Bel Canto Trio, an operatic group that earned huge popularity. It was at a Bel Canto Trio concert at the Hollywood Bowl in August 1947 that Lanza was discovered by Louis B. Mayer, an opera buff and head of the MGM studio. Lanza was not only never to become a true opera star; for some, he was never to be a true opera singer again. He permitted himself to be sucked into the vat of popular culture, always claiming he was doing more for opera in this way than if he were actually to perform in operas: a self-serving, dubious, but not altogether dismissive claim. Lanza was, unquestionably, an integrative figure, an integrative symbol. This was his power and his significance. His undoing was that what he unified was a set of commercialized fantasies which unraveled him both as an image and a person (much the same happened to Elvis Presley, with whom Lanza shares some fascinating similarities.) Two other things should be noted about Lanza by the time he signed with MGM: he married an Irish woman, which annoyed his mother greatly, and he did not want to return to Philadelphia, or Little Italy. While he always remained an ethnic, he felt he had outgrown the old neighborhood.

By 1955, when my mother began her career as a school crossing guard at his former elementary school, Lanza’s Hollywood career had already peaked, but between 1949 and 1953, he was MGM’s biggest box-office attraction. His first three films—That Midnight Kiss, The Toast of New Orleans and The Great Caruso— were among the top-grossing movies of the years of their release. The Caruso bio is now probably his most remembered film. It is certainly the most popular film about opera ever made in America. It is, of course, now a rather complex period piece about the time of Caruso as well as its own time, although it is not a good film, being much in the same vein as other biopics of the era like Houdini with Tony Curtis and The Benny Goodman Story with Steve Allen. These films ideologically were meant, in the 1950s, to symbolize something about American plenitude and the American Dream. The formula was struggling artist eventually makes good because talent will out in the end, marries some WASP woman, or some very WASP-ish looking woman, the biggest social prize the United States can offer a successful ethnic man, dies tragically if the life requires it or lives goldenly if the subject is still living at the time the film is made.

The Great Caruso does not seem to be about opera as much as it is a kind of technologically inventive opera in its own right about ethnic assimilation in the United States, mystifying the Italian-Catholic ethnic as magnificent divo who is not cultured himself but through whom high culture can be expressed and preserved. Lanza simply had to wear tight-fitting, opulent clothes that accentuated his barrel chest, look suitably cute as an ethnic, emote a great deal when singing, and try not to forget his accent too often. In effect, as Caruso, Lanza could personify desire while deflecting the audience from thinking about the nature of desire in general or Caruso’s desires specifically. Lanza was not a gifted actor, but he was a considerable presence, which, in the end, was all Hollywood hired him to be.

The very thing that made Lanza attractive to Hollywood was the source of his undoing in another way: he was a handsome young man who could make operatic singing sexy. Unfortunately for Lanza, he was a big man, weighing normally over 200 pounds. Photography is not kind to heavy people, and Hollywood seemed to have no other way of conceiving someone as sexy except as being relatively thin. When he would go on eating binges, which he did especially as temper tantrums, he could balloon up to as much as 250 pounds or more. Four weeks before the actual filming would begin, Lanza would record the soundtracks of his films. He would then be very heavy, as he, MGM, and the knowing ones of opera were all convinced that opera singers sang better, had better resonance, when they were heavy. But as soon as the recording of the soundtrack was completed, Lanza would have a few weeks in which to lose as much as 50 pounds in order to have the stereotyped appearance of a romantic lead. Lanza’s mad fluctuations in weight played havoc on both his appearance and his health. Toward the end of his career, he suffered from gout, phlebitis and hypertension. Despite rumors about Lanza having been murdered by Lucky Luciano because of a snub, it would seem more likely, until definitive evidence says otherwise, that Lanza died of a heart attack or heart failure as a result of intense dieting.

His death in the fall of 1959 sent Little Italy, Philadelphia, into spasms of grief that bewildered and frightened me as a boy. (Much as Caruso’s death at the age of 48 in 1921 sent the Little Italys of the world into anguish.) The white pop radio stations played nothing but Lanza records. The black stations we listened to most of the time ignored Lanza’s death like he never existed. They simply announced it on their news broadcasts without any commentary. This was my first vague lesson in how to measure the degrees of separation that existed between the worlds of each race. But it did not clearly register with me quite how racial difference worked, and I felt very bad for the bereaved Italians and did not clearly understand why all the blacks I knew did not feel bad themselves or bad for the Italians, too. The banner headline in the October 7, 1959, Philadelphia Daily News that announced Lanza’s death stunned me so much that I was afraid to even touch the paper, let alone look at the comics, which was all I could do with a daily paper at the age of seven. (The huge headline which, along with a picture of Lanza, took up the entire front page, read: MARIO LANZA DIES IN ROME; HEART ATTACK.) This death snapped the sense of stability, of serenity, of my world. Lanza’s death was as surreal and dislocating to me at that age as hearing about a child being raped or murdered, the news stories that most shocked and disturbed me in my childhood. Men and women were literally crying in the streets. Some women actually dressed in mourning. Although Lanza’s improperly embalmed, badly decomposed, bloated, stinking body was buried in Los Angeles, California, St. Mary Magdalene di Pazzi held a memorial service for him, perhaps at the request of some of his relatives in the neighborhood. The place was packed. There were so many long black cars and women and men dressed in black that I thought Lanza was being buried in Philadelphia. Nuns and parents openly expressed their sense of loss to my mother, who felt much saddened by it all, too, not because she was necessarily a fan of Lanza’s, but because these people she had come to know were taking his death very hard. Shortly after, the picture of Lanza and the two lighted candles were placed in the window at 636 Christian Street. I remember that more clearly than any other memorial or monument I saw while growing up in Philadelphia. As I told my wife, who was surprised by that assertion, I saw Lanza’s picture nearly every day for many years of my life. I saw the Liberty Bell only twice.

My

earliest memory of a home in Philadelphia

was an

apartment building where my family lived at 914 East Passyunk Avenue.

That block of Passyunk was entirely Italian except for the apartment building

where only blacks lived, right in the middle of the block. In the earliest

years of my memory, the apartment was filled with people. That is, the

apartments on all three floors were occupied. Each floor had a common

bathroom in the hallway. They were cold-water flats, and my mother always

complained about the lack of heat in the winter, about the general lack

of upkeep. By the time I was five, there were only three families left

in our apartment. One was the Mays, a single mother with six or seven

children. They were very noisy and dirty, although I did like playing

with them. That is, I liked playing with them until they broke my toys.

My mother hated them, thought they were wrecking the apartment building

and shaming the race in front of the whites in the neighborhood.

The other family

I remember from 914 East Passyunk Avenue was the Evanses. They moved to

open a dry cleaning store on the corner of Fifth and Christian streets.

I really liked their oldest son, Ernest Evans, who once risked severe

injury by crossing over one second-story window ledge to another to get

us into our apartment after our mother had accidentally locked us out.

He was my hero after that. He graduated from South Philadelphia High School,

where most of my family went except for me and my sisters. He worked in

a poultry store in the Italian Market on Ninth Street, near either Carpenter

or Washington Avenue. Ernest Evans was a chicken plucker, a very nasty

job that involved not only cleaning the chicken of its feathers in boiling

water but killing the chicken in the first place. Many black boys had

that job in the Italian Market. Places like Giordano’s at the corner of

Ninth Street and Washington Avenue was a popular place to work, if one

wanted that kind of job. It paid well, about $20 or $25 a week. Those

were good wages to a teenage boy from the working class. My mother began

to buy her chickens from the place where Ernest worked, Addio’s Poultry

Shop. Ernest also liked to sing. He very much wanted to be a professional

singer and hung around the offices of a local recording studio called

Cameo-Parkway. Henry Caltabiano, another poultry shop owner, introduced

Evans to Cameo-Parkway Records. Once in a while, in the summer time, on

the front steps, he would sing one of the latest rock-and-roll songs for

us kids grouped around. Only one house on the block had an air conditioner,

so during the summer, everyone was on the street all night. We thought

he was a very good singer; seeming so much older with his processed hair

and knit shirts. In truth, he was a passable singer with the strong appeal

of youth. In 1959, he had a decent hit record called “The Class.” He imitated

other singers very well. Indeed, he was doing an imitation of Fats Domino

one evening at the Cameo-Parkway studio when he got his stage name. Dick

Clark, then the host of American Bandstand, the most popular teen-age

dance show in the United States, taped in Philadelphia at that time, and

his wife were there. Clark’s wife, impressed or amused by Evans’s imitation,

suddenly gave him a new name, and it stuck. Ernest Evans became a rock-and-roll

star under the name of Chubby Checker.

The first record I heard by Chubby Checker was in the summer of 1959, not too long before Mario Lanza died, when he cut “The Class” for Cameo-Parkway Records. It was a modest hit, but all of us who knew him on the block were very proud. We used to sit on the front steps at night—my two sisters, Jimmy and Albert Barbera, who lived next door, Harriet Curci, and several other kids; my sisters and I being the only black ones in the group— and we would listen to a white pop station called WIBG or “Wibbage,” Radio 99. We would wait to hear Chubby Checker’s record. Sometimes, one of the older kids would call the station to make a request. “And this side goes out for the cool kids who hang out on Passyunk Avenue in South Philly,” the disc jockey would say, naming several of us, “A request for one of their own—Chubby Checker.”

I had heard a song called “The Twist” a year earlier in 1958. My mother loved a singer named Hank Ballard and bought all of his records: “Work With Me, Annie,” “Annie Had a Baby,” “Sexy Ways.” She bought a Hank Ballard record in 1958 called “Teardrops on My Letter.” On the B-side was a tune called “The Twist.” It got some airplay on the black radio station we listened to in the house, WDAS. It was not a big hit, but it became a popular dance among black kids in 1959. White kids picked it up from black kids. Dick Clark felt he could cash in on the Twist as a teen-age dance craze but, so one version of the story goes, not with Hank Ballard as the singer, as he was an R-and-B artist associated with lewd material and a lewd stage act. Chubby Checker was, essentially, not an R-and-B act; he was not associated with black popular music, so, in a sense, he was a kind of raceless black man. In any case, Checker made a hasty cover of the tune at Cameo-Parkway for Dick Clark’s American Bandstand show. In the late summer of 1960, the song, heavily promoted by Clark, hit number one on the charts. However the story goes, it turned out to be one of the most politically significant covers in the history of rock-and-roll music. For the first time one black artist covered another and turned a song into a huge crossover hit. And Checker became the first bona-fide black teen-age idol, a clean-cut image for white kids. White girls loved him, and the powers and princes of popular culture did not see this as a threat. For a few years, Chubby Checker was one of the most powerful integrative forces in American popular music. He was only 19 years old when “The Twist” went number one.

My mother was, at first, shocked when she heard Checker singing “The Twist.” “He sounds just like Hank Ballard,” she said. He did, indeed, every vocal inflection, every Ballard mannerism, every nuance. It was uncanny. How can he have a hit when he sounds just like Ballard? My mother never quite forgave Checker that bit of plagiarism and, on principle, always preferred the Ballard version of the song. We kids were proud of Chubby Checker anyway. We were amazed that someone we knew had a hit record, was a recording star. Another thing that amazed me when I grew older was that not a single white kid I knew I had heard Hank Ballard’s version or heard of it. Ballard’s “The Twist” was played on the local soul station, but Checker’s “The Twist” was played on both the local soul station and the white pop station. The Twist as a dance lasted about six months among the kids I knew, among my uncles and aunts, who were very young at the time. Soon after, kids were doing the Stomp, the Gully, the Crossfire and the Watusi.

Chubby Checker’s career might have ended right there as a one-hit wonder except that the Twist caught on as a dance for hip and not-so-hip adults. By the fall of 1961, the Cafe Society began slumming at places like the Peppermint Lounge at 47th Street and East Seventh Avenue. From 10:30 p.m to 3:00 a.m., one could find people such as Greta Garbo, Noel Coward, Tennessee Williams and Elsa Maxwell dancing the Twist, or simply listening to a five-piece band called Joey Dee and the Starlighters. Checker’s “The Twist” emerged again and became a number-one hit in early 1962. The dance was so big that a new wave of whites began slumming at places like Small’s Paradise in Harlem, owned at this time by basketball star Wilt Chamberlain, to Twist and watch Negroes Twist. More whites began going to Harlem nightspots than at any time since the Harlem Renaissance.

Meanwhile, stores were flooded with Chubby Checker ties, Chubby Checker belts, Chubby Checker towels, and even instructional records by Checker teaching the listener how to Twist. He was not only the first black teen idol. He was the first black to have merchandise marketed to the American public. In this civil-rights era, Checker was truly, though very inadvertently, a remarkable figure, something seminal in a political and sociological way. He made it seem very natural to me for blacks and whites to be together. He was the personification of integration, of the inclusive community. His estimated income for 1962 was a cool million. He released other successful records on Cameo-Parkway, like “Let’s Twist Again,” “It’s Pony Time” (my favorite Checker record even today), “The Fly,” “The Hucklebuck” (a Charlie Parker tune with vocals; Parker sold the rights to the tune in a recording studio lavatory for a drug fix), and “Slow Twisting” with another South Philadelphia singer, Dee Dee Sharp. What did all this Twist madness mean? “I don’t know,” Checker said, “People do it and they forget things.”

At this time, I was in the same fifth-grade class as Chubby Checker’s youngest brother, Spencer. And his middle brother, Tracy, was dating my oldest sister. He would drive up in these fancy Cadillacs and Stingrays and the Italian-Catholics—kids and adults—would be very impressed. By the end of the 1962 school term, Checker’s family moved from the neighborhood to a big, $30,000 house in a very upper-middle-class, integrated area of Germantown. Tracy continued to date my sister for a while but that eventually petered out. One year later, my family moved from 914 East Passyunk Avenue to a small house around the corner at 918 South Sheridan Street, where I lived until 1975. Once Chubby Checker’s family and the Mays family moved, we were the only people left in the building. At this time, there was a great deal of talk about an Interstate being built that would run through this part of South Philadelphia. There was a great deal of worry among the residents and a good deal of resistance on the part of the Italians. The Crosstown Expressway, as it was called, never happened, but the threat of it changed the demographics of South Philadelphia and made it possible for a certain type of intense re-gentrification to take place that largely resulted in loading more black folk into projects or forcing them to other parts of the city.

The threat of the Expressway made selling the apartment more difficult but not impossible. My mother knew that very soon we would have to move. She had become very friendly with the Italian family down the street, the Curcis. Their home on Passyunk had a smaller attached home that fronted on a small side street right behind Passyunk called Sheridan. One of their sons had been the lodger, but he married and moved to New Jersey, so they were now looking for a tenant. My mother came back home one day, ecstatic with the news that the Curcis had decided to rent the home to us. I am not quite sure why they did, as this was, without question, going against the conventions of the moment. But we developed a very close relationship with this family over the years, at least as close as a relationship between blacks and Italians can reasonably get. All of the Curcis were especially fond of me, which was sometimes a cause of embarrassment when I was with my black friends. “How come them dagoes like you so much?” they would ask when we were out of earshot. We moved into the house in the late spring of 1963. We were the only black people in the immediate vicinity of Little Italy.

On the Thursday before Labor Day, 1963, a black couple, Horace Baker, a lab technician, and his wife, Sara, tried to move into 2002 Heather Road in a community called Delmar Village in Folcroft, Pennsylvania, a short drive outside Philadelphia. They were driven from the home twice that day by whites throwing bricks and bottles. That night, the whites pulled out all the plumbing fixtures in the home and wrecked the furnace and hot-water heater. The family finally moved in on Friday, but a mob of 1,500 whites stoned the house after they moved inside. Every window in the house was broken. The doors were virtually torn off the hinges. One hundred state troopers were required to prevent the mob from murdering or maiming the family.

On that same Tuesday, the school year started and my mother was back on the job crossing the Italian-Catholic kids. Many of the parents, the nuns, and priests, mentioned the Folcroft incident to my mother, out of a kind of nervousness, perhaps, as it was the age that put racial nerves on edge, or out of a sort of kindness or an attempt to reach some understanding with the only Negro most of them knew. Most were ashamed of what had happened. But many told my mother that this business of integration cannot be forced. “People can’t change overnight,” they would say. “Besides, not all families are like yours, Florence. Not all families can fit in. Some make trouble. I think this integration is going too fast.” My mother would simply nod. What, as a black person, could you say to a statement like that? After all, as my mother told me and my sisters privately, it was the white folks in Folcroft who were making all the trouble. The black family hadn’t done anything any of us could detect as causing trouble except move into a house or try to.

“As a black, I have been getting kicked in the ass by this country for centuries, but what’s a few more decades of getting kicked in the ass if it makes you white folk feel more comfortable with the fact that I might be a human being, too! Well, excuse me for living!” This was the common sentiment I heard expressed at the black barbershop I went to. “Don’t stop suffering,” I remember hearing Malcolm X say sarcastically in a recording of one of his speeches at the time. “Just suffer peacefully.” Or as another barbershop patron put it: “The Bakers got what they deserved. They ain’t had no business moving out there in the first place with them white folks. I say this: why should anybody think that my highest aspiration is to live next to these dog-like white folks. Let ’em keep their goddam neighborhoods and the sanctity of their white asses, too.” There was, at this moment, and for the rest of the time I lived among the Italian-Catholics, a certain, unstated, but very compelling and dramatic kind of stress, as if one represented one’s whole race all the time, was the sole testament to its claim of humanity. And yet there was a certain perverse, oddly ironic pride in being considered the exception. I could scarcely understand it, then.

It was near Christmas in 1964 and I was walking through downtown department stores with my middle sister, Rosalind. I admired Rosalind because she was older and smarter. She just knew and knew and knew. And what a reader she was! Her favorite expression was a line the congregation said during our church service: “As it was in the beginning is now and ever shall be, world without end, Amen.” She especially liked the idea of “a world without end.” “Do you know what that means, Jerry?” she said to me once. “It means the world goes on no matter what. God promised us the world and gave it to us. It’s up to us to live up to that promise.” Rosalind and I always spent a great deal of time together, and at Christmas particularly we would go around to the all the stores, Lit Brothers, Strawbridge and Clothier, Gimbel’s and Wanamaker’s, and gaze at the Christmas decorations, walk through the toy departments, listen to the choirs sing, get jostled by the huge crowd of shoppers on Market, Chestnut and Walnut Streets. It was a cold Christmas season as I remember it, and 1964 had been a strange year. In December of 1963, Chubby Checker married a Dutch woman, Catharina Lodders, Miss World of 1962. It came as a shock to everyone. The Italian kids I knew resented it tremendously and began to ridicule Checker. “He oughta stay with his own kind,” I heard them say. Mr. Addio and my mother spent the whole of 1964 talking about this marriage, about how Checker had ruined his career as a result. “The public’s not for that,” I remember Mr. Addio saying. “You can’t buck the public. And you know, Florence, the white kids made Chubby and now they’re gonna break him. He can’t do this. He’s not big enough. It almost killed Sammy Davis, Jr. when he married May Britt. And he had Sinatra behind him. These colored guys gotta marry in their own race. Why not marry a colored woman? What’s the matter with those colored guys? They ashamed of their race or somethin’? You can’t do this kind of thing. Have some white girl on the side. But don’t marry one. The public ain’t ready for this, Florence.”

He may have been right, as Checker’s career began to slide steadily in 1964. But part of this was undoubtedly because he had hitched his artistic wagon to the star of teen-age dance crazes. This gimmick was bound to run its course in short order, and Checker had little creativity as either a singer or a songwriter. Amazingly, he had 20 Top 40 hits between 1959 and 1964. His marriage, which everyone talked about in South Philadelphia for a long time, probably just accelerated the slide a bit. It did not create it. Checker, from his very name to his imitative style of singing to the blatantly silly songs he sang, was too much of a pop novelty not to fade. In any case, when he married a white beauty queen, the black teen pop idol who had been a kind of raceless figure, or a black who had transcended the limitations of his category, suddenly and intensely, became very racialized and very much a category, indeed.

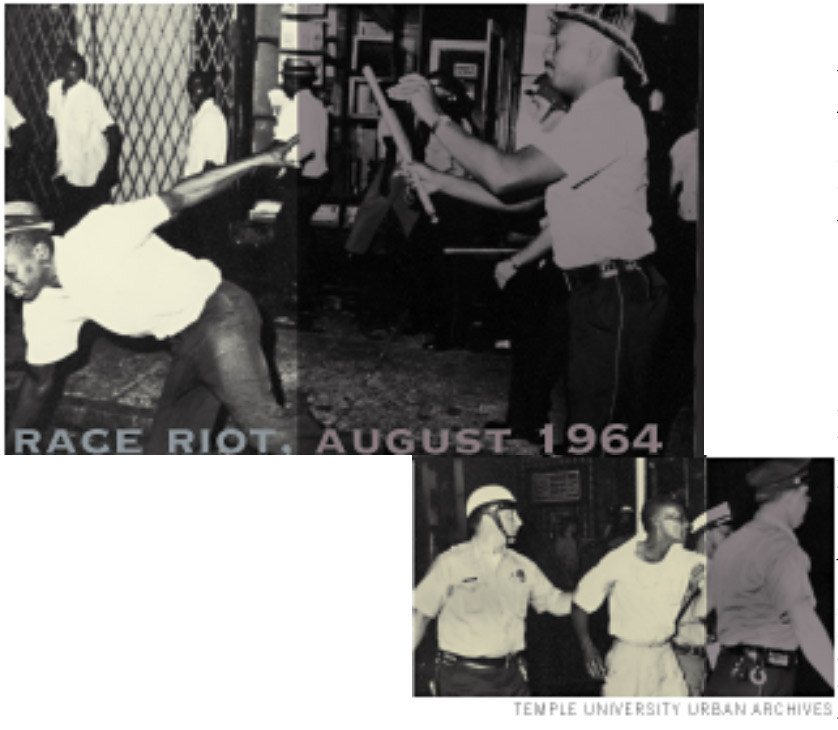

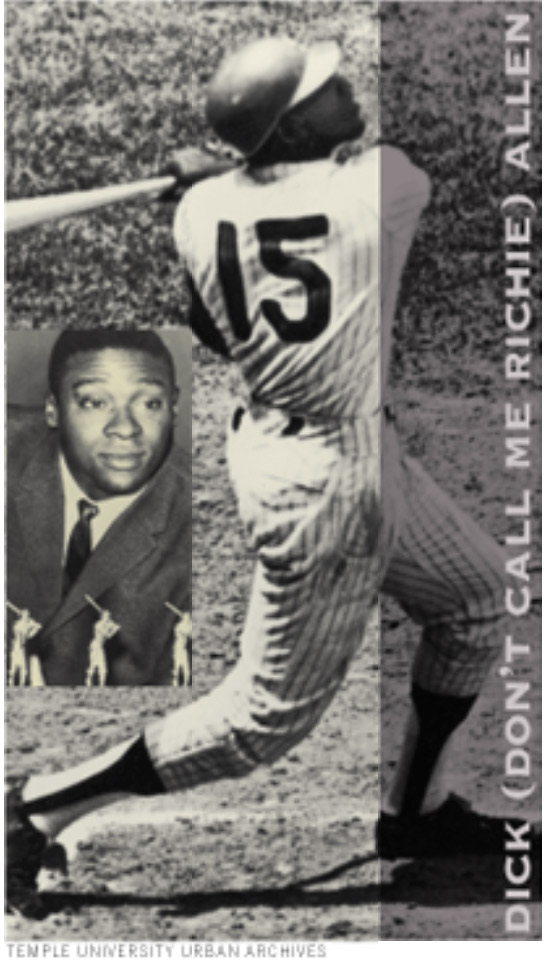

On the weekend before the Labor Day weekend in 1964, as I was all a twitter about the Philadelphia Phillies’ run for the National League Pennant, with their first Negro superstar, Dick (Don’t Call Me Richie) Allen, who was on his way to becoming rookie of the year, a race riot broke out in North Philadelphia, the biggest Negro ghetto in Philadelphia, a tough neighborhood that I avoided except on the few instances my sisters took me to see a rock and roll show at the Uptown at Broad and Dauphin or I went with some friends or my grandfather to a Phillies game at Connie Mack Stadium at 21st and Lehigh Streets, still a section of North Philadelphia with a fair number of whites at this late date of 1964, but they were leaving in droves.

Racial tensions had been high in Philadelphia all year, especially over the issue of police brutality. The Philadelphia Tribune, the city’s black newspaper, ran articles in virtually every edition on police brutality. White policemen who were brought up on charges were routinely acquitted.

The riot started on Friday night at 9:35 P.M., August 28, 1964, when a woman named Odessa Bradford, a 39-year old waitress (or 34-years old, depending on which source one consults), driving a vehicle on Columbia Avenue with her husband, Rush, got into an argument with two police officers, one black, Robert Wells, and the other white, John Hoff, after their car stalled at 23rd Street and Columbia Avenue (or 22nd Street and Columbia, once again depending on the source). When Mrs. Bradford refused to move the car, the police officer tried to remove her bodily from it. Mrs. Bradford resisted mightily. At this point, a crowd gathered, shouting, “You wouldn’t manhandle a white woman like you did this lady.” A melee ensued in which two police officers were injured and the Bradfords were arrested. Mrs. Bradford bit one of the cops who tried to remove her from the car. James Mettles, 41, a bystander, came to Mrs. Bradford’s aid and attacked the police officers. He was arrested. Rumor spread along Columbia Avenue and its environs that a pregnant black woman had been beaten to death by a white cop. This rumor was started by Raymond Hall, 25, a neighborhood agitator affiliated with no political organization. By nightfall, marauding bands of black looters smashed into stores on Columbia Avenue and cleaned them out. A few years ago, a black lawyer told me that when, as a teenager going to school, she walked along Columbia Avenue a few days after the riot, the smashed plate glass was nearly ankle-deep. It crunched under her feet like an icy snow. Policemen, severely outnumbered by the rioters, were ordered by Police Commissioner Howard Leary, who grew up in what had been the Irish Catholic section of North Philadelphia and worked his way through Temple University Law School at night, to do nothing. Frank Rizzo, who was to become, before the end of the 1960s, the police commissioner, and by 1971, the mayor, and was in 1964 the famous, most admired, and most hated, cop in Philadelphia, intensely disliked this strategy, feeling that a strong show of police force would nip the riot in the bud. He called Leary “a gutless bastard.”

By Sunday, the fury was all spent, but nearly every store on Columbia Avenue, the central shopping district of North Philadelphia, had been destroyed. The riot signaled the beginning of the end of North Philadelphia as a largely working-poor neighborhood. (It also signaled the rise of Frank Rizzo, the Italian-Catholic from South Philadelphia, drop-out from South Philadelphia High School, who was to wrestle control of the city from both the WASP patricians and the Irish.) Many of the stores never reopened, and the neighborhood began its descent into the chaos of an underclass realm. “If that policeman had only treated me like a human being,” Mrs. Bradford said afterwards, “none of this would have happened.” It seemed so far away from me, this riot. North Philadelphia seemed like another world. I only knew that many of the black cops my mother knew were working a lot of overtime that summer and seemed glad of it.

Nineteen sixty-four was my baseball year. I had mastered stickball, softball, and baseball so that I was considered a good player. Guys wanted me on their teams. For hours at a stretch I would throw a rubber ball against a wall, playing out whole games in my imagination while I strengthened my arm. I often played with Italian kids, as baseball and stickball were far more popular with them than with my black friends. On the occasions when the black boys got together a team to play the Italian kids, the Italians would insist that I had to be on their side because I lived in their neighborhood. And so, in the oddest of scenarios of integration, I would play, most of the time, for the white team against my black friends and the blacks did not mind at all. After the game, I would often go off with my black friends to play pinball, and no one would mention that I had just played against them. Sometimes I went off with the white kids to talk baseball. On Father’s Day of 1964, my baseball year, right-hander Jim Bunning of the Phillies pitched a perfect game against the Mets. It was the first game of a doubleheader that I watched on television. I thought it was an omen of things to come. No matter, it was not the Phillies’ year. With only 12 games left and a six game lead, the Phillies proceeded to lose 10 games in a row. The Cardinals won the pennant and the Phillies finished third.

Dick Allen was

one of the greatest athletes ever to play for a professional team in Philadelphia.

Old Number 15. He was, without question, the best offensive player, and

probably the best pure athlete on the 1964 Phillies. (He was a horrible

fielder in his rookie year: he made over 40 errors. He would never in

his career be anything more than an adequate fielder, at best.) In his

rookie year, he wore glasses, giving his face the appearance of a schoolboy.

His body was like that of a halfback. He gave me chills whenever he came

to bat. He was clearly indulged when he came to the Majors. He was a strange

man, for at times he seemed not to care about playing baseball at all.

He would disappear for several games. No one, not even his family, apparently,

knew where he was. He drank a lot, sometimes while playing. He smoked

heavily, often during games. It was difficult to tell from his habits

whether he was inattentive to his great athletic abilities or stressed

by them. And the fact that he was treated special, combined with his moodiness,

was a cause of great friction with the fans, especially white fans, during

his entire time in Philadelphia. Some of the Italian kids I lived with

felt Allen was a major reason the Phillies died down the stretch: “Colored

guys can’t take the pressure. They choke.”

“Them white guys

always talking about Allen choking,” said one of the black men in my barber

shop, “but they never ask themselves where the team would have been without

Allen. They would never have been fighting for a pennant at all.” Allen

gave black kids something to cheer about; it was unlikely they would have

paid the team any attention at all had Allen not been on it. The Phillies

had a bad reputation in the black community of Philadelphia since the

days of Jackie Robinson, when then-Philadelphia manager Ben Chapman needled

him so viciously.

Many others blamed

Gene Mauch—indeed, in my neighborhood, Mauch was virtually execrated for

the team’s demise. Allen, in his autobiography, Crash: The Life and

Times of Dick Allen, expressed this view: “The problem with Gene Mauch

as a field general in 1964—and it haunted him to his retirement—was that

he held the game too tightly in his hand. Mauch was a brilliant strategist.

I learned more about baseball as a chess game under Gene Mauch than I

did under anybody else in baseball. The man’s a master of the little game—when

to bunt, how to steal a sign, what base to throw to, all the ways to outthink

your opponent. But Gene Mauch never let us play the game instinctively—and

without that you can’t win enough baseball games to capture a flag … Once

we started to skid, Mauch became a wild man. After losses, he would close

the clubhouse door and start dressing us down, throwing things around.

After one particular loss in that ten-game streak, Mauch stood up on a

table in the clubhouse and began telling us what a good marriage he had

and how for the good of the team we should all follow his lead. I think

maybe Gene lost it at that point …” So, the blacks of North Philadelphia

had their nervous breakdown in August and the Phillies, led by Gene Mauch,

having caught the virus, had theirs in September. A cordon of police surrounded

Connie Mack Stadium during the days of the riot. There was a great deal

to think about that Christmas. So much had happened for a 12-year old

to understand.

It was perhaps

Christmas Eve or the day before Christmas Eve that my middle sister and

I were walking around among the stores in Center City, Philadelphia. The

song you could hear everywhere was “Downtown” by Petula Clark. By January

23, 1965, it would be number one. It was a special song of the city that

year, just like Martha Reeves and the Vandellas’ “Dancing in the Street”

was earlier that summer, a song that, ironically, took on a heavier political

significance than its singers or its composers ever imagined. During the

riot, “Dancing in the Street” became the song of the Revolution, the song

of the new dispensation. It seemed so strange to me that a song of such

happiness like “Dancing in the Street”—“all we need is music, sweet music”—was

connected with such an act of misery and anger. All of us in Philadelphia

felt good about the song because our town was one Martha Reeves called

out for special attention in the lyrics. Now, in December, August and

the riot seemed a long time ago. “Downtown” was a different song, for

a different time, for, in effect, a different city. I remember a colleague

of mine, a specialist in African culture, told me a few years ago that

that song had a significant effect on rural people in Tanzania when they

heard it. “It made city life seem so attractive that many of them simply

left the farm and crowded into the city, much to their own economic disadvantage,

as it turned out,” he said.

On that day,

right before Christmas, walking with my sister in the cold, helping her

buy her presents for everyone in the family, hearing that song made me

suddenly and achingly feel the glory and power of the city, this city.

For the city was the adventure of inadvertent contact, often meaningless

and sometimes irritating. But as we bumbled along in this huge anonymity

like so many estranged atoms we sometimes bumped and bonded. “And you

may find somebody kind to help and understand you/someone who is just

like you …” But what the song suggested was that the accident of finding

someone like yourself could not be predicated merely by a similarity of

appearance. For if it were outer appearance that truly mattered, only

the most tribal similarities, why leave the neighborhood? The city is

this ironic romanticism, this cheap but transcendent realism.

I was, as a boy,

blinded by the light show of the city, its magic, its aura, the fervent

hope that next year will be better. Next year the Phillies will win the

pennant. Next year the stores on Columbia Avenue will re-open. Next year

Chubby Checker will have another hit record. No road is more golden with

hope and promise than an innocent’s unobstructed view of the future. So,

I pinned my soul upon the wondrous architecture of this unstoppable, manmade

frontier of streets, and buildings, and parks, and people, pressed against

the magnificent firmament. O Heavenly City! “This is my city,” Frank Rizzo

always said, and I felt his same ownership. Our city, I thought, and it

means something to be from this city, to live in this city. How could

those black folk in North Philadelphia want to burn down their neighborhood?

How could they want to burn what was their city, too? This is what it

means to be an American, I thought as a boy, to live in this place and

to feel this way. And I was not to learn fully for several years yet what

it meant to be the particular type of American I was.

I could not imagine

anything better than this, the roaring buses, the lumbering trolleys,

the busy merchants, the fancy rowhouses of Society Hill we passed on the

way home, the downtown movie theaters. “The lights are much brighter there/

You can forget all your troubles/ Forget all your cares/ And go Downtown.”

We went to the Boyd theater or some other downtown theater that day and

saw a film. I cannot remember what it was, only that it must have been

wondrous and colorful. We stopped by our small church, St. Mary’s Episcopal

Church at 18th and Bainbridge Streets, an Episcopal parish mission started

specifically for West Indian and city blacks back in the 19th century,

to get my red cassock and surplice. I was an altar boy and had to have

my vestments cleaned and pressed for the midnight mass on Christmas Eve.

So we walked about Center City, I with vestments probably being mistaken

for a Catholic, and my sister with her packages, leading the way: Scout

and the sidekick, Old Red Ryder and Little Beaver, Zorro and Bernardo,

Don Quixote and Sancho we were. It was time when I was supposed to be

thinking of this other life, the baby Jesus, but there was no other reality

for me on these streets but these streets. I did not want that life, not

that new possibility of the other life. All I could think of was that

there could be no better life than this. It was all and everything for

me. There could be no other life. As it was in the beginning is now and

ever shall be, world without end! I was so wildly happy, so utterly and

completely filled by the possibilities of this life, the riches of this

city, so lushly endowed by the company of my sister and her shopping,

I turned to her and said with joy, “I want no other life but this one.

No other life.” And then I said to God, silently, “Please let there be

no other life. Let me live no other life but this one.”

Gerald Early C’74 is the Merle Kling Professor of Modern Letters at Washington University, St. Louis. This article is excerpted from a longer piece titled, “The Lights Are Much Brighter There,” which appeared in Three Essays: Reflections on the American Century, published by Washington University and Missouri Historical Society Press.