A new permanent exhibition of Etruscan, Greek, and Roman artifacts is both a loving restoration/update of the University Museum’s classical galleries and a dramatic exploration of the links among these key civilizations of the ancient Mediterranean.

It’s a new world at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology—in fact, three of them.

The March opening of “Worlds Intertwined: Etruscans, Greeks, and Romans,” was the culmination of a $3 million, 10-year effort to create a suite of modern galleries to display the Museum’s rich collection of objects from these cultures and to enlighten visitors on the histories and links among the great classical civilizations of Greece and Rome and the lesser-known Etruscans, the first rulers of central Italy.

Added to the Greek World gallery, which opened in 1994, the new spaces are bright and open-feeling—a reasonable approximation of the sunny climate of the Mediterranean—thanks to a combination of modern lighting and design and the restoration of some original building features obscured over the years, such as vaulted windows and a skylight that had been covered over. The artfully displayed objects are organized around thematic concepts—daily life, childhood, trade, etc.—and augmented by maps, videos, and wall-mounted texts designed to give visitors “a better sense of who these ancient classical peoples were—and how their vision of the world continues to influence us today,” in the words of Dr. Donald White, curator-in-charge of the Museum’s Mediterranean section.

In all, there are some 1,000 objects on display, including marble and bronze sculptures, jewelry, metalwork, mosaics, glass vessels, gold and silver coins, and pottery. To give readers some sense of what the galleries have to offer, we asked Dr. White and the other curators involved in organizing the exhibition to select and describe some of their favorite artifacts.—JP

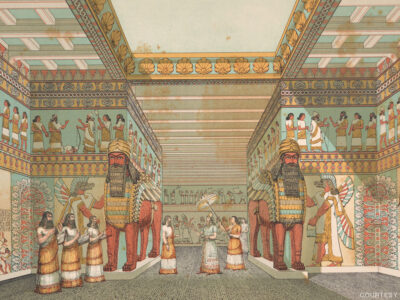

The Etruscan World

early seventh century B.C.

Footed Bowl From Narce

One of the strengths of our Etruscan collection is a series of tomb groups that came to the Museum in the mid-1890s. Especially noteworthy are those from the site of Narce, in the area known as the Faliscan zone, between southern Etruria and Rome. The Faliscans were Etruria’s near neighbors, and their culture was distinct from but closely related to that of the Etruscans.

This footed bowl, dating from the seventh century B.C., is from a wealthy woman’s tomb, one of three of our Narce tomb groups included in the Etruscan gallery. On its rim stands a man between horses, and the composition displays the angularity and abstraction that is characteristic of much Etruscan and Faliscan art, and it is really appealing to the modern eye.

One can learn a great deal from complete groups of grave goods, and in this case we can tell something about the woman who owned this bowl. She was probably the wife of the warrior whose tomb contents are also on exhibition, for the warrior’s tomb contained a footed bowl clearly made in the same workshop as this one. The only difference is that while her bowl shows a man between horses, the warrior’s vase is decorated with the “mistress of horses”—a woman between horses. It is possible that the two vases were exchanged in a betrothal or wedding ceremony.

—Dr. Ann Brownlee, co-curator and senior research scientist, Mediterranean Section

An Etruscan’s Helmet

The businesslike, Etruscan “Negau” helmet isn’t from Negau in Slovenia, but the type’s namesake was found there. It looks plain, but the pot-shaped, cast-bronze helmet (made circa 500 B.C. in an armory in the city of Vulci) in a way symbolizes the whole of Etruscan culture. The culmination of the aspirations of the Etruscans’ Iron Age warrior ancestors, it tells of the zenith of Etruscan society, technology, and history, and foreshadows their political demise that consigned them to the histories written by Greek and Roman enemies. Two similar helmets now in the British Museum were fished out of the River Alph at Olympia, where they once formed part of a trophy erected by “[king] Hieron and the Syracusans,” who took them from Etruscan marines defeated in 474 B.C. by a Greek-Roman coalition in the naval battle of Cumae off the Bay of Naples. Etruscans had dominated central Italy and the Tyrrhenian shipping lanes since about 700 B.C., but after Cumae, they would be absorbed city by city as Rome grew. By the first century B.C., they had become tame citizens of Rome.

—Dr. Jean MacIntosh Turfa, consulting curator for the Etruscan Gallery

The Greek World

Greek Runners

This Attic black-figure lekythos depicts two runners racing in either the stadionrace (600 feet) or the diaulosrace (1200 feet) between two judges on the racecourse. The naked runners wear red fillets on their heads. The vase was made in Athens in about 550 B.C. and likely depicts an athletic event from the Panathenaic Games, a part of the largest religious festival of the city, including both musical and athletic contests held in honor of its patron goddess, Athena. The Panathenaic Festival was one of the largest and most famous local festivals in the Greek world in which athletic victors were given prize amphoras filled with olive oil. The vase, about 0.29 meters high, was excavated from a chamber tomb at Narce in Italy.

The two runners on this vase have been used as the model for a new U.S. postage stamp to be issued in conjunction with the 2004 Olympic Games.

Philip II and the Olympic Games

This silver tetradrahm, struck in Macedonia, depicts a walking horse and rider on its reverse side. The naked rider holds a palm branch symbolizing victory. The obverse side shows a bearded silhouette of Zeus, a portrait of the colossal gold and ivory cult image of Zeus by Pheidias that was housed in the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. The coin was manufactured by Philip II, King of Macedonia, to commemorate his victory in the horse race at the Olympic games in 356 B.C. The letters above and to the right side of the horse spell out, “of Philip,” referring to the victory.

The Roman writer Plutarch in his Life of Alexandertells us that Philip received three messages on the same day in the summer of 356. The first told of the victory of one of his generals, Parmenio, over the Illyrians; the second mentioned the victory of his race horse at Olympia; and the third told of the birth of his son Alexander. Clearly Philip was not at Olympia during this contest, nor did he come in 352 or 348 B.C., when his equestrian teams won two additional victories there. Later, in 338 B.C., Philip defeated the allied forces of the Greeks at Chaeronea to assume leadership of the Greek states.

—Dr. David Gilman Romano Gr’81, senior research scientist, Mediterranean Section

The Benghazi Venus

The malodorous salt-flats outside of the eastern Libyan city of Benghazi may have once marked the location of legendary Lake Tritonis and its island Temple of Aphrodite, today covered with a Moslem cemetery. This area is the place of origin of the Museum’s exquisite statuette of a naked Aphrodite daintily wringing the salt-water out of her hair while she rises from the sea—under the circumstances not unlike a gorgeous butterfly emerging from an ugly caterpillar. Carved from large-grain gray-white Parian marble, she rises less than 13 inches above her cut-off thighs. While some have argued that she might have been originally displayed standing thigh-deep in a pool of water, the angles of the cuts make her appear to be toppling backward. Perhaps she was damaged in antiquity, since laboratory analysis reveals no signs of her having been reshaped in modern times—nor clad in separately carved drapery below the waist for that matter. Her type ultimately derives from a famous lost masterpiece by the painter Apelles from the island of Cos. Goddess of physical desire and carnal sex, her raw physicality has been muted here by the figure’s refined carving and the slightly blurry, “veiled” expression achieved around the eyes by the deliberate crushing of the marble’s crystalline surface (unless she was over-cleaned with dilute acid before she came to the museum, a possibility one would just as soon overlook!). One of the smaller examples of the stone carver’s craft in the Museum’s collection, she is also one of our very finest, exemplifying perfectly the Greeks’ renowned abilities to create masterpieces in miniature.

—Donald White

The Roman World

inset: Detail of symbolic rope decoration.

The Museum’s Lead Coffin

Purchased in 1895 from a Newark, New Jersey, dealer with roundabout connections with the Museum, our third-century Roman lead coffin reveals its story in a symbolic language that is not easily deciphered. While both abundant and relatively cheap, lead carried for the ancients the stigma of being gold’s opposite. While gold was “noble,” lead was “base.” The gloomy planet Saturn, itself thought to be made of lead, was associated with decaying old age and death, while the life-giving sun was thought to be of gold. And if bright gold symbolized the perpetuation of life, its cold and dark opposite was used to engender destruction and death as the preferred medium on which to write curses and magic spells. The coffin’s long sides are covered in low relief with Medusa heads and dolphins surrounded by laurel and ivy leaves; one of the short ends pictures the facade of a Corinthian temple, the other an eight-spoked “rope star” design interspersed with more ivy. All of these devices are symbolically connected with either the cult of Dionysus, which promised its initiates an existence beyond the grave, or the repulsion of evil spirits and demons. But the coffin’s most arcane message lies in the triple lines of twisted rope that bind its box lengthwise and doubtlessly would have looped over the missing lid to seal its vaulted cover firmly in place. The Roman world was popularly believed to swarm with malignant spirits, succubi, and ghosts, and nowhere were they more apt to be found than in a cemetery. The ropes consequently serve a dual purpose, the one preventative, the other prophylactic. The first was designed to keep external spirits from harming the dead, the other to keep the ghost of the deceased from escaping its coffin to wander abroad and molest the living.

—Donald White

of Diana, Nemi.

Diana’s Gifts

“No one who has seen that calm water, lapped in a green hollow of the Alban Hills, can ever forget it,” wrote Sir James Frazer in the opening sentences of his 1890 opus The Golden Bough, which immortalized Nemi and the myths associated with Diana’s cult along the lake. Since antiquity, Lake Nemi and the virgin huntress Diana’s important sanctuary on its shores have been the stuff of legend, lore, and artistic inspiration. Lake Nemi is located just south of Rome in the cool and wooded Alban Hills, where Aeneas roamed and where the rich and well-connected have kept vacation villas since Republican Roman times.

The Museum’s collection of 45 pieces of marble sculpture from the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis, acquired in 1896, were among the first for the newly founded Museum. The collection is made up of mostly late-second-century B.C. votive statuettes and a set of inscribed marble vessels of early Imperial date, all gifts to Diana from devotees, as well as fragments of cult statues of Diana that would have been set in one of her temples. A display on the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in the Roman World gallery, which includes many of these sculptures with a mural backdrop of the lake, is my favorite part of the exhibition.

—Dr. Irene Bald Romano Gr’80, research associate in the Mediterranean Section, co-curator and coordinator.