Archival inks on Hanhemuhle Photo Rag Ultra Smooth paper.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art debuts new galleries with an exhibition featuring faculty and alumni.

Posters sketchily chronicle stories of the recently departed—their details sometimes lurid, sometimes mundane—in sentence fragments printed in red and black, set in myriad fonts, and laid out in staggered lines. Videos follow a dozen Philadelphians who wander in and out of the pretty rooms of a Germantown house, flopping onto sofas and beds to read passages from activist pamphlets. Jacquard fabrics depict a rocky coastline and dense palm foliage while an accompanying screen shows footage of ice floes and polar bears.

These strikingly different pieces, each created by an artist currently on the faculty of the Stuart Weitzman School of Design, are just a handful of the 100-plus works by 25 locally based artists that comprise New Grit: Art & Philly Now, the inaugural exhibition of the Daniel W. Dietrich II Galleries at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Dedicated to showcasing modern and contemporary art, the eight galleries are part of a larger Frank Gehry-designed expansion. A rare collaboration across curatorial departments that also spans generations, media, and cultural backgrounds, New Grit attempts to “take the pulse of Philadelphia art today,” says associate curator Erica Battle C’03. The Penn trio described above is as diverse as the overall body of artists presented, but Battle sees some similarities among them. “They are all very conceptual and research-based,” she observes. “They are guided first by ideas, then the materials and media follow.”

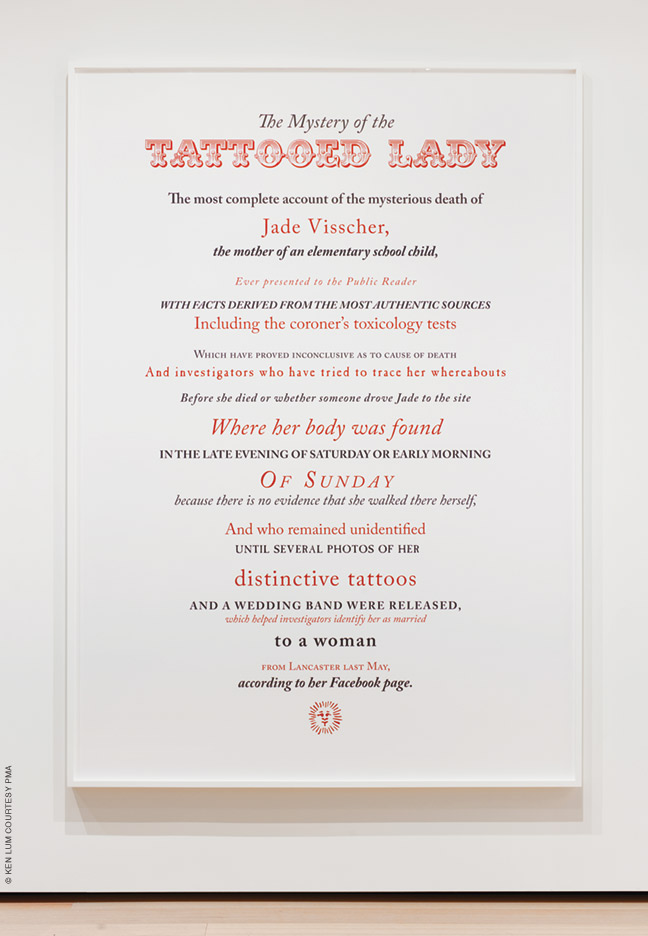

In their work here, all three also examine the past from a social justice perspective. The text-based portraits of the Necrology series (2017) by Ken Lum, chair of fine arts, are fictional lives crafted from a mix of obituaries and personal recollections. They are written in snatches of old-timey, florid prose reminiscent of 18th- and 19th-century frontispiece illustrations that faced the title pages of many books during that period. On view in a gallery thematically devoted to “The Epic and the Everyday,” the works are, Lum says, “infused with not just stories of ordinariness but with politics and the stresses that people have to bear in their lives due to class, race, and gender.”

Lum conceived of Necrology in 2015, when the Philadelphia Inquirer reprinted its original announcement of Abraham Lincoln’s death 150 years earlier. “It had all these subheads, starting with Born in a log cabin and ending with A nation mourns,” he says. “I thought, ‘Wow, the entire life of Lincoln is like a haiku.’ The text was so pictorial, and I’m always interested in the intersection of image and text.”

The disjointed details presented in Lum’s pieces—keypunch operator Charlotte Wilson Turner was the seventh of 10 children; Lucy Santos once supported her parents and siblings in Manila by “retrieving value from garbage”—give viewers tantalizing hints about, but not a complete picture of, the subject. “You get the constitution of a person that you don’t actually see,” says Lum. “It’s like reading a novel, where there’s a constant oscillation between the words and your imaginings.”

Fine arts professor Sharon Hayes’ In My Little Corner of the World, Anyone Would Love You (2016) also uses documentary material, taking inspiration from the Hall Carpenter Archives, a collection dedicated to the recent history of gay activism in Britain. There Hayes found a “fertile environment that circled back to my ongoing and persistent interest in the near past,” she says. “It’s a past that isn’t resolved and continues to insert itself into present political discourse.” Situated at the end of a gallery called “Memory and Belonging,” her piece—whose title cleverly references a 1960 tune by Anita Bryant, the pop singer turned orange juice spokesperson turned outspoken anti-gay crusader—greets visitors with a plywood wall pasted with reproductions of letters to the editor and bulletins announcing upcoming demonstrations.

Around the corner from these panels, a 37-minute video introduces viewers to a cast of local LGBQT personalities who come and go, alone and in varied pairs, reading aloud and typing excerpts of tracts and correspondence from feminist, lesbian, and trans newsletters produced in the US and UK from 1955 to 1977. “I most vehemently object to this harsh criticism and find it extremely difficult to believe that my dress could have wounded anybody,” one performer pronounces. “On the contrary, I have been wounded by certain members of the group…”

Hayes modeled her installation after domestic spaces. “We think of protest happening on the public street or square, but these communities found danger in that kind of setting,” she explains. “The members of this collective are meant to be floating in time, as well as in place. They are ghosts in this house, occupying the specter of a reader, the specter of a writer, the specter of an editor.”

Jacquard woven tapestry; single-channel 4k video.

In his enigmatic work, The Histories (Crepuscule) (2020), David Hartt, the Carrafiell Assistant Professor in Fine Arts, also mixes video with other media. Music, textiles, and photography come together in his piece. Conceptually inspired by the writings of Herodotus, and particularly the Greek historian’s interest in the movement of people and goods, the work is one of five specially commissioned for this exhibition. A tapestry of two photographs that Hartt made in Jamaica and video footage he shot of shifting ice floes off the coast of Newfoundland recreate works that 19th-century American landscape painter Frederic Church made depicting the same scenes.

The juxtaposition of the arctic and the tropic is meant to suggest historical and economic linkages that are not explicitly referenced in the art. “What the work really deals with is histories of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade,” Hartt says. “Canada absolutely participated in the slave trade, but it doesn’t have the same sense of connection or even responsibility for it [as the United States]. As a Canadian,” he adds, “I’m trying to understand the dimensions of these entangled moments in history.” A moody soundtrack emitting from a vintage Panasonic shortwave radio adds more layers to these already turbulent histories. Performed by the electronic musician Pole, it’s a contemporary riff on Crépuscule, composed by Oswald Russell, a Jamaican pianist who enjoyed international fame during the latter half of the 20th-century.

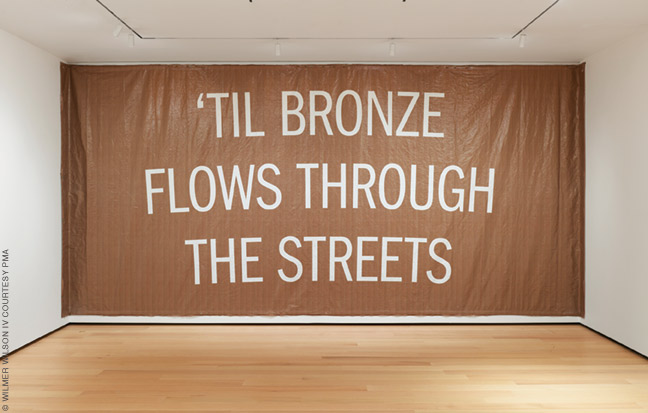

Hartt’s work occupies one end of a gallery called “(Un)Natural Histories,” which also includes several pieces by Micah Danges, manager of the Silverstein Digital Projects Lab at Weitzman. Of particular note are two “windows” suspended from the ceiling of the gallery that feature photographic images of lush hanging plants printed on mesh. Acting as bookends for a gallery titled “Crossing Boundaries,” alumnus Wilmer Wilson IV GFA’15 offers two vinyl banners that he had initially shown in his native Richmond, Virginia, last summer when the city’s Civil War monuments were being questioned. (One piece addresses melting down the statues with a simple statement that reads Til Bronze Flows Through the Street in white letters printed on a brown background.) “There was a question at first of how do we display objects that have a little grime, some wear and tear,” says Battle. “But their weather-beaten look and lack of preciousness is materially very important.”

Battle says that the exhibition, conceived three or four years ago, “was always about looking at Philadelphia as a catalyst for creativity. But,” she adds, “it became a really generative process for the artists in the wake of what we all experienced last year. It was really exciting to do something with these artists who—like everyone in the world—went through some kind of transformation, and to produce a show that doesn’t just react to but embraces those changes.”

—JoAnn Greco