For 25 years, Penn’s small Native American community has tried to grow its presence on campus, through lively powwows, Ivy League conferences, and student and faculty outreach. But trying to shed the “feeling of being invisible” has been a perennial struggle.

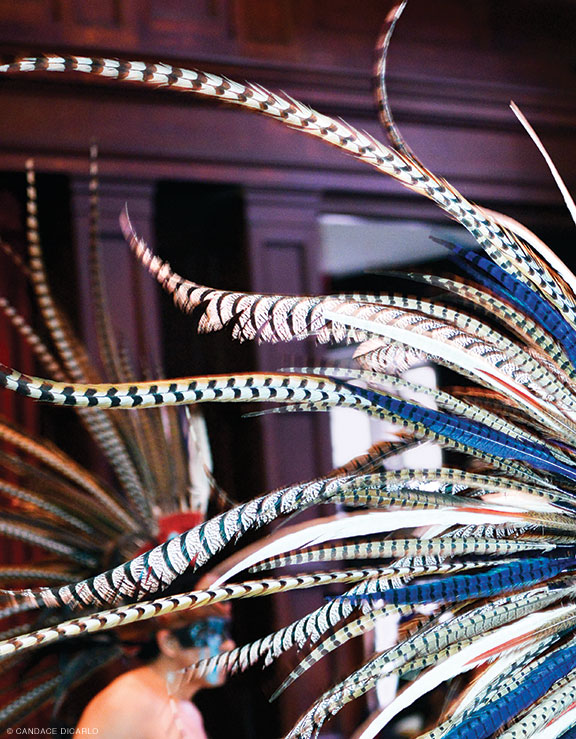

BY DAVE ZEITLIN | Photography by Candace diCarlo

When the drumming stops and the dancers sit, Talon Bazille Ducheneaux C’15 takes the microphone. He speaks slowly, powerfully. “I just wanted to say I’m really appreciative and proud and honored to be a part of this community,” he says, looking around at the people gathered inside Houston Hall for the 10th annual powwow put on by Natives at Penn (NAP), the University’s student group for Native Americans celebrating its 25th anniversary.

The crowd, filled with traveling Native American drum groups and dancers from tribes around the region, looks larger than it did seven years ago when—then a Penn freshman—Ducheneaux was asked to emcee the powwow with just two days’ notice. He wasn’t given a schedule for the event, which was then held outdoors. It was cold. And rainy. And sparsely attended. A much different affair than this year’s crowded powwow, which lasted almost seven hours on March 31 and was modeled more closely on the traditional social gatherings Native Americans hold to honor their cultures. “Seeing you all and seeing where this powwow is,” he says, “it’s amazing that it’s been 10 years. There seems to be continuity and structure and validity to what we’re doing.”

Continuity and structure are two things Ducheneaux didn’t have for much of his life, and validity is something he’s always chased. Growing up on two reservations in South Dakota (Cheyenne River and Crow Creek), he says he “witnessed the best part of Native success and the worst parts of its destruction.” His parents were “big into drugs and alcohol” and moved around a lot before divorcing. Friends suffered from addiction too. He had to travel a good hour just to buy groceries at the nearest Walmart. The opportunity to leave the reservation for an Ivy League school made him feel like “almost a celebrity,” with some people telling him how awesome it was but others giving off an Oh-he-thinks-he’s-better-than-us vibe. “Coming to Penn, I had an opportunity to figure out for four years: Who am I? What am I doing? What do I want to represent?” After first making the 1,500-mile journey to Philly in his red Mazda, he tried to lay low. But it didn’t take long for him to realize that if he wanted Native Americans to gain more validity on college campuses, he had to represent everything: his people, his family, his tribe, his home. “It’s a lot of unfair responsibility they put on us at 18,” he sighs.

After hooking on with NAP and finding “a second home” at the Greenfield Intercultural Center (GIC), where the group is housed, he met several other Penn students with Native backgrounds, from different tribes and parts of the country. Learning about each other’s identities proved to be eye-opening for him—as it was for others. “You don’t have to look a certain way to be Native,” explains Jules Crain C’16, who admits that her ancestors’ heritage “wasn’t a huge part of my life” before NAP invited her to a welcome dinner her first week at Penn. “And now,” she says, “I’m texting everyone saying, ‘Come to powwow!’”

Others in the group haven’t always felt that closely connected to their Native roots, either. Sam Garr EAS’21 is the group’s copresident, just like his brother, Paul Garr C’10 once was. But because he’s “mostly Irish” with pale skin, he says he doesn’t generally bring up the fact that his mom’s side of the family is distantly related to the Ojibwe Indians in Michigan. “We just think it’s cool to have our roots go that far back,” says Garr, who helps organize the powwows, as well as group meetings, welcome dinners, and conferences for all of the Ivy League’s student Native groups, including one Penn hosted last spring.

Erica Dienes W’19, who ran the group with Garr this past year, shares a similar outlook. “I look white. I don’t really harp on it,” says Dienes, from the Poarch Band of Creek Indians in southern Alabama. “I don’t go around saying, ‘I’m Indian.’” But she does try to publicize that there are Native Americans on campus—and that you might not know they’re walking past you on Locust Walk or sitting next to you in history class. “It deserves to be talked about,” she says. “It’s more about recognition than anything.”

That’s why inviting Native Americans to sing and dance in traditional regalia right next to where students study and buy crepes has been important to Dienes. And this particular powwow carried even more meaning as she and classmate Kaylee Slusser C’19 were honored as NAP graduates by recent alums Keturah Peters Nu’18 and Crain, who wrapped them in a Native-made blanket. Ducheneaux—a hip-hop musician [“Saved by the Beats,” Sept|Oct 2015] who flew in from South Dakota for the powwow—stood in between them during the ceremony and closed with a prayer song. Before that, he sat at a table on the mezzanine level overlooking Houston Hall’s Hall of Flags, selling his artwork and music.

“I like coming out here because I would like Penn to keep building better representation and connection with Native people,” he says. Next to his table, a vendor sells finger puppets, coyote teeth, and Native craftwork. Further down the row, jewelry, handmade soaps, and shaking sticks vie for attention along with shirts with phrases like “Make America Native Again,” “No One is Illegal,” and “The Original Founding Fathers.”

“We started from such humble beginnings,” Ducheneaux says. “Even before I was here, you see pictures and it’s like 10 people, tops. But now every time I see this, it’s awesome—because it’s progress.”

Too often, though, progress has felt like an uphill battle.

From the Ground Up

Desiree Martinez C’95 never caught the name of the graduate student who noticed her beaded hair clip outside of an American Civilization class and asked if she was a Native like her. But she’ll never forget what that student said to her that day. “She started telling me about issues she had in terms of being alone,” Martinez says, recalling that neither of them had known at the time—in the early 1990s at Penn—if there were any other Native Americans on campus besides them. “She actually contemplated suicide because there was nobody there who could understand the issues she had to deal with.” Martinez felt horrible and “wanted to do something. I just didn’t know what to do.”

Soon, it became clear. In the fall of 1992, Martinez received an invitation to attend a meeting at GIC with other known students who identified as Native American. The goal was to start a group since “Penn was supporting all of these other communities,” Martinez says, “and yet wasn’t supporting the Native community whatsoever.” Not much progress was initially made, so the next year Martinez asked if she could take the reins. By the beginning of the fall semester in 1993, an article in the Daily Pennsylvanian announced the arrival of “the University’s first organized cultural group for Native Americans.” It was called “Six Directions,” a name Martinez chose because the four cardinal directions are very important in Native American culture, and a push was made to include two additional “directions”—the sky and the ground. By February 1994, Six Directions received recognition as an official member of the United Minorities Council. “I’m really excited and happy and surprised at how fast everything happened,” Martinez said at the time to the DP, which claimed that of the 17 Native Americans enrolled at Penn, 11 were members of Six Directions.

Martinez, now an archaeologist, secured funding from Penn’s Student Activities Council, reached out to other Ivy League schools about Native American programming, and pressed the admissions office to try to increase the number of Native applicants. “We started hard and heavy,” she says. “We had a lot of meetings on campus demanding better recruitment, to talk about retention issues—just harassing people to start thinking about Native issues.” But once she graduated, she admitted there was a bit of a lull. Bryan Brayboy GEd’95 Gr’99—a graduate student who now serves as a professor of Indigenous education and justice at Arizona State University—stepped in to drive Six Directions forward. But it still went through ebbs and flows over the next decade, depending largely on the number of Natives in each particular class and their dedication in growing the group.

When Megan Red Shirt-Shaw C’11 arrived on campus in 2007, membership had fallen to a low point. As a sophomore, en route to an Ivy Native Council conference, she was asked if she could take over the group along with Paul Garr—whom she had just met, in the car, moments earlier. Red Shirt-Shaw and Garr accepted, and made two significant changes. First, they changed the name from Six Directions to Natives at Penn. “We just wanted it to be clearer for people to be able to find us,” Red Shirt-Shaw says. And then they planned a powwow for 2010, billing it as the “first annual” powwow even though Martinez had organized one just after the group was launched in 1993. The hope was that the word annual would “create an expectation that it would continue.”

“I think all of us, as undergraduate and graduate students, had experienced the feeling of being invisible on campus, whether it was in classrooms or just by people we considered our friends who had maybe never encountered a Native person before,” Red Shirt-Shaw says. “I think one of the big goals of hosting that first powwow is we really wanted to be visible and wanted to do it in a place where no one was able to ignore our power and presence.” That place was Locust Walk, outside of Van Pelt Library. And even though it turned into more of a showcase than a full-blown powwow because there weren’t enough dancers, Red Shirt-Shaw was thrilled to see classmates stop by on their way to class to watch.

She was even more thrilled to watch from afar as the powwow became an annual tradition as she had hoped, growing every year in size and scope with more and more traveling Native American communities attending. “I get extremely emotional and excited every time I see the photographs now, because I remember being an undergraduate and all of us wanting to make it happen and wanting it to live on,” she says. “Just seeing that it has, it was worth all of the late nights and early mornings we spent putting that first one together.”

To truly be seen on campus, however, more was needed besides singing and dancing.

“We’re in Academia”

When Tina Pierce Fragoso was in second grade, she remembers being told to sit down and be quiet after she spoke out against a history book’s claim that Native Americans were “extinct”—and the teacher who was reciting it. But that incident didn’t discourage her; it only stiffened her resolve.

Fragoso, who now works in Penn’s admissions office as a coordinator of Native American recruitment, hasn’t shied away from a battle since, focusing her undergraduate and graduate studies—at Princeton and Stanford, respectively—on writing tribal histories through anthropology. And before starting at Penn in 2009, she served her Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape community in New Jersey, doing everything from archival work to writing grants to helping people get into college. “We have to continue to educate,” she says, “to make sure the next generations can also say they’re Native.”

In her 10 years at Penn, she’s helped the University make significant inroads in recruiting Native American students and providing resources for them once they arrive on campus. One of those students was Ducheneaux, who had never heard of Penn until Fragoso paid a visit to his South Dakota high school. He later made the most of his time at Penn by emceeing NAP’s then-burgeoning powwows and helming a panel discussion on Native hip-hop artists in conjunction with Penn Museum’s Native American Voices exhibition [“Know That We Are Still Here,” July|Aug 2014]. Still, the lack of Native faculty members made the more traditional parts of his college experience frustrating. “There were times when I would be in certain classes that were Native-based, and they would look at me after their lecture and be like, ‘Was that good, Talon?’” he recalls. “I’m paying tuition! You tell me if that’s good!”

Luckily, support came elsewhere. Steve Johnson W’89—a former Penn football standout best known as “Chief” because of his roots in the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan—got to know Ducheneaux and was blown away by his backstory and artistic talents. “Whatever you do, don’t lose that kid,” Johnson remembers his father telling him. And he didn’t, using his connections to George Weiss W’65 Hon’14, a University trustee and prominent Penn football philanthropist, to step in to help Ducheneaux deal with a financial aid problem that threatened his stay on campus. That kind of rapport between Native alums and students has been on the rise since the 2006 founding of Penn’s Association of Native Alumni, whose stated aims are to foster “the renewal of old friendships and development of new ones,” while furthering “Penn’s commitment to the advancement of Native American higher education.”

As a student whose biggest connections were forged on the football field and in his Sigma Chi fraternity house, Johnson was far more isolated than those who came after him. He didn’t know any other Natives on campus and took only one American folklore class, taught by a non-Native. (“I thought it would be an easy A,” he says. “I got an A–minus.”) After graduating, he told Weiss that it “just seems wrong” that Penn didn’t have more Native American students and faculty members, and Weiss, Johnson says, “put me in contact with people at College Hall” to let them know it’s a problem.

Change happened slowly. The hiring of Fragoso years later helped boost the admission numbers of Native Americans. According to Dean of Admissions Eric Furda C’87, this year’s incoming class has 34 students that self-identified as Native American and last year’s class had 23—a sharp rise from the six that arrived on campus in 2008, as reported by the Daily Pennsylvanian. Still, some of the same concerns about representation persisted after Fragoso’s arrival. “The students who put on the first of the 10 powwows were making a push for having more Native faculty and staff,” recalls Fragoso, who was asked by those students to help organize that powwow because they didn’t know where else to turn.

The push had modest success. According to GIC director Valerie De Cruz, there are now at least three professors of Native descent: Margaret Bruchac in the anthropology department, who is the coordinator of Penn’s Native American and Indigenous Studies program (which, starting in 2014, is now offered as a minor) [“Old Penn,” this issue]; Maggie Blackhawk at Penn Law; and Evelyn Galban at Penn Vet. De Cruz also notes that other administrators, like Kenric Tsethlikai, managing director of the Lauder Institute, have been mentors to Native students for years.And although De Cruz would like to see the University “create more robust programming” for Native American studies, she was encouraged that faculty members and other staffers banded together last year to form the Penn Native Community Council, which she calls a “game changer.”

“Often people don’t realize we’re still here, or we’re in academia, or we look like everybody else,” says Toyce Holmes, a counselor for Penn’s Upward Bound college preparatory program. That’s why she joined the staff council, hoping it can both be a support system for Native students and also shine a light on contemporary issues facing Native Americans. “It’s just to make sure that there’s a presence here, that people know Natives are still doing great things, and we’re not a conquered people,” she says, adding that Indian mascots and portrayals of “the poor Native on a reservation” have “perpetuated stereotypes” for too long.

Dienes was grateful to get that kind of support during her four years on campus. “I think one thing that’s special about this group, that maybe other groups don’t have, is that our close-knit relationships expand to faculty and administrators,” Dienes says, before adding, “People just don’t recognize this culture is persistent.”

“Penn Can Be Home”

Sitting in the backyard of the GIC one day this spring, De Cruz hears the banging and drilling coming from next door, where a luxury condominium complex is rising.

About six years earlier, GIC’s backyard was transformed into a “Lenape Garden” to honor Penn’s Native American roots and create “a place at Penn that recognizes this is Lenape land and recognizes the lives and traditions of the Lenape people.” Led by Ann Dapice Nu’74 Gr’80, the Association of Native Alumni partnered with NAP and University landscape architect Bob Lundgren GLA’82 to build a garden in the shape of a turtle—a symbol of the Lenape people—and surround it with trees and plants native to the region. At least until the construction began, it was a reflective place where students would come, De Cruz notes, when they wanted “some peace and quiet.”

Laura Lagunez Gr’20, a graduate student in Penn’s public health program and a NAP mentor, is grateful for such a space and the recognition that the University indeed sits on what was once Lenape land. But coming from Cornell University—where she was the resident hall director for Akwe:kon, the first Native American dorm in the United States—she knows Penn still has a long way to go to catch up with Cornell and other institutions with more pronounced Native American support, such as Dartmouth (whose 1769 charter proclaims the college was in part created “for the education and instruction of Youth of the Indian Tribes in this land,” and which, 200 years later, created various Native American academic and social programs) and Stanford (which also made a push starting around 1970 to boost Native programming and enrollment while dumping its old “Indian” mascot). “Very much at the beginning, I had uninformed optimism,” Lagunez admits. “I thought, We’re going to do all these things, get all of these students involved, make all of these institutional changes. But then more and more throughout the last semester, I realized, Oh no, this is a very different experience.”

Lagunez (who has cultural roots to her Navajo and Nahua Mexican ancestry) and De Cruz (a non-Native) both note there can be advantages to having a smaller Native community than a place like Cornell, Dartmouth, or Stanford, where De Cruz posits it might be “really hard if you’re a Sam Garr to actually have a presence in the room—whereas here our students embrace anyone who is genuinely interested.” Lagunez adds that she’s been working with incoming NAP cochair Connor Beard C’21 on being more welcoming and “really trying to see what students are here on campus who may not feel like they can claim their indigenous heritage because they didn’t grow up on the reservation.” [See this issue’s “Notes from the Undergrad” for one student’s perspective.]

According to Garr, only about “five or six people” came to all of the NAP meetings this past year—compared to what he heard is approximately 80 at Dartmouth. But even with a small group, Lagunez says “it would be great” if Penn’s indigenous students could get their own building, rather than sharing one at GIC with other minority groups. Vanessa Iyua Tiyankova SPP’11, who served as associate director at GIC from 2011 to 2016, has a similar vision but understands the establishment of a Native American center might not happen for many years. More immediately, she hopes Penn does more to recognize the history of its land by partnering with local Lenape tribes, while also doing more to support the work being done by Fragoso in the admissions office. The goal, as it always has been, is to inform the Penn community that Native Americans still exist—and that there are ways to partner with them.

“Even today,” Tiyankova says, “I still get stereotypical questions like: Do you live in teepees? Do you have running water? Do you have electricity? I just wish people knew our history a little better and that the Native community is still vibrant and present and that we’re still fighting for who we are every day.”

Tiyankova praised De Cruz as one of the “greatest Native allies,” and pointed to some of the “wonderful things” alums of the group are doing as proof of NAP’s growth under her guidance. On top of Ducheneaux’s music career and Brayboy’s teaching, Peters has worked on health issues facing her Wampanoag tribe in Mashpee, Massachusetts. And Red Shirt-Shaw is a good example of someone who used her time at Penn to inform her career. She’s worked in admissions at several colleges and is currently pursuing a PhD in higher education at the University of Minnesota, with an “ultimate dream” of starting a high school close to where her mom, of the Oglala Lakota tribe, grew up in South Dakota. “I want there to be more opportunities to create college prep for Native students,” Red Shirt-Shaw says. “I just really want more Native students to be at college, so they don’t have to experience those same feelings I felt as a freshman when I first walked onto campus.”

While Penn and other colleges might have more work still to do, Red Shirt-Shaw is encouraged by what she’s seen over the past decade. “Change is slow but certain,” she says, adding that she cried during the Ivy Native Council Spring Conference that Penn hosted in 2018, because she could not have imagined such an event on campus when she was a student.

“You want to be able to come back and see the students outdo what you were even capable of doing as an undergraduate,” Red Shirt-Shaw says. “That’s the ultimate goal: I want every generation to do something we weren’t able to do.”

Taking stock of NAP after more than 25 years of existence, some have wondered what Penn’s Native American community might look like 25 years from now. Can the University catch up to other colleges with longer-running Native student groups and more established Indigenous programming? The rise of the powwow and the formation of the Penn Native Community Council are certainly promising developments—but is that enough to draw and retain more Native American students? Considering Penn’s Native community dates back to 1755, when two Mohawk Indian brothers, Jonathan and Philip Gayienquitioga, attended what is now Penn, according to Penn Archives, should the University be doing more to embrace its deep cultural ties to Native Americans?

“I think part of the struggle is that sometimes the perception, both outside of Penn and even within Penn, is that it’s hard to recruit Native students because Stanford, Cornell, and Dartmouth have a lock on it,” De Cruz says. “The prevailing notion is: we just can’t compete. That’s just nonsense.”

It’s a perception some Native Americans will keep fighting to change, just as they’ve fought many other battles, over decades and centuries.

“I want to see more Native students going to college and feeling that a place like Penn can be home for them,” Red Shirt-Shaw says. “Many generations are working very hard to make that a reality.”