An upsurge of bright silver.

By Nick Lyons

Nearly seven decades ago I simultaneously fell in love with literature and a tall girl with frizzy hair. I had never been in love with girls or books before and lived most of my days in dumb terror. The poetry of Donne, after the insurance I had studied for my undergraduate degree, was as alien to me as Swahili. The poetry and girl, swarming in my head, led me to stumble about the campus of Bard College, where I had registered as a freshman, in a daze, muttering like a madman.

Naturally I had taken my rod and reel and a small bag of fishing tackle, and all that terrible fall and winter I kept eyeing the stream that formed the southern edge of the school property in a happy series of runs, riffles, sharp bends, and deep plunge pools. By opening day of trout season on April 1st, I could stand the tension no longer. I dug half a dozen worms behind one of the men’s dorms, readied my gear, and slipped away into a cold, drizzly, predawn morning. Mist rose from the stream at the sweeping bend I had spotted behind the math professor’s house. I waded into the lower end of the turn, in the shallows, and shuffled closer where I thought the trout would be lying. My sneakers held back none of the icy water.

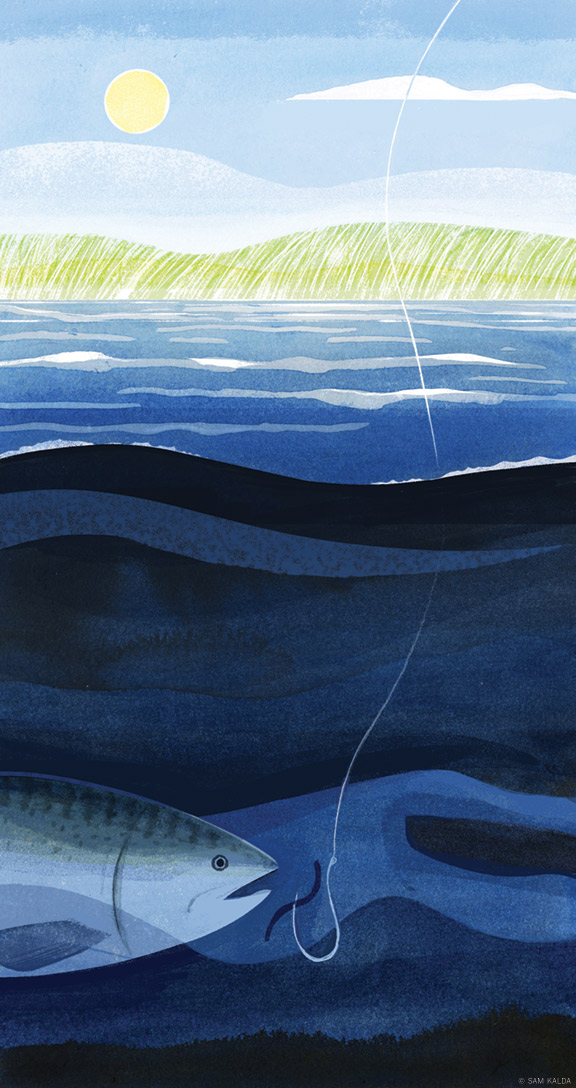

On my first cast, a little upstream, I felt a slight tug, a slow tightening of the line, and there was an explosion: in an upsurge of bright silver, rising like Excalibur from the dark water, a great fish rose high, then higher, then bent double and shook, suspended in the cold air, then leapt twice again, burnished silver, a fish larger than any I had ever caught or even seen. I may have peed in my pants but I couldn’t tell for I had followed the great fish into water higher than my waist. It had to be a salmon—but from a small creek in the Hudson Valley?

My line was thick. The hook was placed deep. The enormous silver fish had little chance. In a few minutes it rolled twice, leapt once more half-heartedly, and then skittered onto the shallow bar and turned slightly to one side. I high-stepped toward it and then threw my whole body on the poor creature, trapping it against my chest in the frigid shallows and grasping it with both hands. Its head and shoulder were all that fit into my shoulder bag.

Still dripping wet, I promptly took the fish to meet my friend with the frizzy hair. Half asleep she smiled and mumbled something like, “That’s a nice little fish, Nicki,” and then turned back to the pillow. Then I took it to show the novelist who I knew to be a serious brother of the angle and he reported that, yes, it was definitely a salmon.

That night the wife of the chair of the English department baked the fish whole. When it came out of the oven it was placed upon a salver large and bright enough to please a king. Her husband, a poet, recited Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “The Fish,” with its haunting ending in which she lets the fish go. I loved the poem but had done nothing of the kind, and half an hour later the group of us had reduced the lovely fish to a backbone and a head. Our talk ranged between that strange thing called “literature” and my prize fish and I felt a happy sense that the two could be joined, especially when the frizzy-haired girl pressed my arm warmly when I snuck in a few words that sounded half-intelligent. As the pleasant evening unfolded the novelist remembered hearing that the owner of the great estate, who had left his mansion and lands to the college, had stocked the stream with great specimens of exotic fish.

That explained my salmon, and in the next few weeks I caught a splendid ouananiche under one of the falls, a fat lake-sized brookie, and a brown trout of unusual girth.

The girl with the frizzy hair, a painter, gave me a watercolor from memory of the salmon, and we soon married, had four children, and spent 58 years together, madly in love.

I have since caught many remarkable fish on flies in far-flung famous waters. But none has remained as vividly etched in my brain as that fish caught in a time of first loves: that poor Atlantic salmon in the small Hudson Valley creek with a fatal lust for a worm.

Nick Lyons W’53 is the author, most recently, of Fire in the Straw: Notes on Inventing a Life [“Writing Lives,” May|Jun 2021]. This essay will appear in My Catch of a Lifetime, ed. Peter Kaminsky (Artisan, 2023).