History says the catcher’s mitt was invented by Joe Gunson, a 19th-century catcher. The real inventor may have been a Penn dentist and ballplayer who wanted to preserve his hands for his dental career.

The dentist was Albert “Doc” Bushong, who matriculated at the dental school (then the brand-new Department of Dentistry) in 1878 and received his dental degree in 1882.

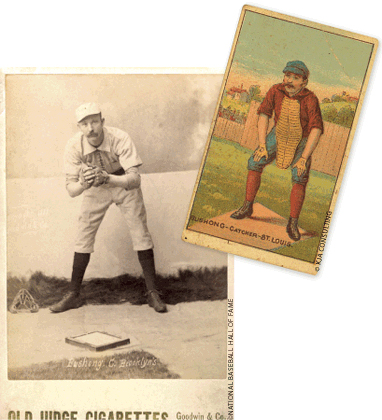

By then he was already an old pro, having begun his professional baseball career by catching one game for the Brooklyn Atlantics in 1875. He played briefly with the Philadelphia Athletics during the National League’s inaugural season in 1876, played minor-league ball for three seasons, and reached the majors again in 1880 with the Worcester Rubylegs.

Bushong was thus the first of 19 Penn medical or dental alumni who, over the next 53 years, also played major-league baseball. After graduation he continued to play major-league ball, and had a pretty interesting career. He was the first major-leaguer to catch at least 100 games in a season, and he played in five 19th-century “World Series”—postseason exhibitions between the two league champions.

In his first World Series, in 1885, he was at bat when the series-winning run came home on a passed ball, an event immortalized as the “$15,000 slide.” The team owner was so pleased he arranged for several western towns to be named after team members—resulting, in this case, in Bushong, Kansas.

He also may have invented the catcher’s mitt. Hard as it is to believe, before 1875 catchers caught barehanded, making it an even more painful occupation than it is now. One commentator noted that shaking hands with a catcher was like “grasping a handful of peanuts.” Then catchers started using a pair of thick work gloves behind the plate, with the fingertips cut off one hand to facilitate throwing—an imperfect solution.

Sources generally credit the invention of the catcher’s mitt to journeyman catcher Joe Gunson in 1888. Accounts have Gunson securing wool padding and a wire frame to a leather work glove with the fingers sewn together, then encasing everything in a buckskin sleeve. Decades later Gunson claimed that he “foolishly explained to [a teammate] the exact making of it,” and then shortly thereafter “everybody began to make them.” According to Gunson he was never able to patent the invention.

An account in the January 24, 1915 edition of The New York Times, however, credits Doc Bushong with the invention. Bushong “was very careful about his fingers, as he intended practicing dentistry after his days as a ballplayer were over,” the article noted. “He wore the largest glove he could find, and had added pads until it looked like a pillow. Out of Bushong’s idea grew the idea of the mitt.”

The way the invention was reported fits Bushong’s attitude towards his dual careers. He made it clear that, while he was a major-leaguer, he was also a dentist. He even studied dentistry in France after the 1883 season, and speculation over his possible retirement ended only when it was announced that Cleveland would allow him to report one month after the season started, so he could complete his studies. An 1887 injury was extensively covered, perhaps because of possible implications for his dental career. “Dr. A.J. Bushong is now in St. Louis, nursing a broken finger,” began the story, followed by a long description of the accident and an expression of regret from the opposing team’s president.

Some even attributed Bushong’s defensive talents to his dental training. “‘Doc’ Bushong’s unusual ability as a catcher is believed by some to be due to his profession of dentistry,” asserted one writer. “He yanks in a foul tip in just the same style that he yanks a three inch molar from a big granger’s fly-trap.”

Did Bushong invent the catcher’s mitt? The Times account does not date his invention, but perhaps the strongest argument is Bushong’s well-documented concern over preserving his hands for dentistry. He did break his finger in 1887, and obviously didn’t want to repeat the experience. If he started using his padded glove when he returned from his injury, he would have beaten Gunson by one season. There are no reports of hand injuries for Bushong after the 1887 incident, and he continued to catch for three seasons. While 19th-century reporting is spotty, it’s still likely that if Bushong had suffered more hand injuries they would have been noted. Could his mitt have protected his hands?

Bushong’s claim is strengthened by the respective descriptions of his and Gunson’s inventions. Gunson’s mitt consisted of a leather glove, with fingers sewn together, attached to a wire frame holding additional padding. This prototype bears little resemblance to a modern mitt in either composition or function. Mitts are not composed of a distinct glove floating in a structure of padding; nor are there wires or their modern equivalent (plastic?) in modern mitts. Moreover, the catching technique dictated by such a mitt is neither efficient nor modern. The sewn-together fingers would make it more difficult to encircle the ball with the hand, as catchers do with modern mitts.

Bushong’s mitt, by comparison, is based on enlarged padded fingers. While modern mitts do not have distinct fingers, the placement of fingers in the modern mitt mimics that which would occur with padded, enlarged glove fingers. With modern finger placement comes modern catching technique, and it’s easy to see the mitt evolving to accommodate the technique allowed by Bushong’s invention—and much less so by Gunson’s.

Gunson’s claim does not have the unqualified support of experts, either. Freddy Berowski, research associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, says he “can’t say [Gunson’s claim] holds more merit” than competing claims. Hall of Fame curator Tom Shieber cautions against thinking that the catcher’s mitt sprang forth as a complete invention—there “may not have been an inception moment here,” he says—but adds that “Bushong may very well have played a role” in the evolution of the mitt.

This perhaps-unrecognized inventor retired from baseball in 1890 and pursued dentistry full-time, first in Hoboken, New Jersey, and eventually in Brooklyn. His brother, Charles A. Bushong, and his son, Stuart Franklin Bushong, also studied dentistry at Penn. Bushong died in 1906, heralded by at least one newspaper as “one of the most famous baseball catchers in the country.”

—Steve Eschenbach