“We have this desperation as writers to feel that we’re important,” Norman Mailer was saying to a group of students at the Kelly Writers House in late February. Especially, he added, because there’s “very little evidence” to reinforce the illusion of importance.

Mailer was responding to a gentle jab from his old friend Bob Lucid, emeritus professor of English, for having taken credit for some ancient political triumph (helping John F. Kennedy squeak past Richard Nixon in 1960 on the strength of a political article that Mailer wrote shortly before the election). But although the political and literary landscapes have changed enormously since then, the desperate sentiment has not.

It had been nearly a decade since Mailer last spent serious time on Penn’s campus [“Toward a Concept of Norman Mailer,” May 1995], and even longer since his appearance was a Big Event for students. But he hasn’t lost his presence or his intellectual vitality, and he still comes as close to swaggering as is possible for a short, 81-year-old man who leans on two canes.

During his conversation with the students, he focused mostly on politics, using his recent book, Why Are We At War? as a point of departure.

“The terrible thing about politics, and the most exciting thing about it, is that there’s a genie in the bottle,” said Mailer in his engaging growl. “The finest principles in the world in politics always converge with an audience, which is why the art of politics is timing—which is why perfectly ordinary people often become successful in politics, and brilliant people often fail. It’s because one has a sense of timing and the other doesn’t.

“You get very pent up when you’re writing about politics. There’s an anger that burns and burns,” he said—especially in the age of television, when he for one finds it easy to see “what an absolute oaf and fraud and mountebank and phony fundamentalist” George W. Bush is. But given that Americans can no longer cope with answers that last more than 10 seconds, he added, “We now have the president we deserve.”

It came as no surprise that Mailer heaped scorn upon the American-led invasion of Iraq, including the notion that we were coming to liberate its people.

“If you’re living under tyranny,” he said, “it’s up to you to get out of it.”

“Fascism is more of a natural state than democracy,” he argued in his book. “To assume blithely that we can export democracy into any country we choose can serve paradoxically to encourage more fascism at home and abroad.”

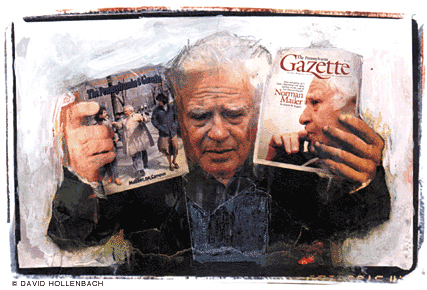

Mailer’s visit also included a question and answer session at Writers House that evening. Bob Lucid handled the introductions—and occasionally clarified questions for the hard-of-hearing Mailer. To demonstrate Mailer’s 30-year history of Penn appearances, Lucid held up a pair of Gazette covers marking his 1995 visit and an earlier one in 1983; and while Mailer didn’t make the cover in 1975, he had been a Connaissance Fellow at Penn that year.

He spoke mostly about writing in this session, with frequent reference to The Spooky Art, the recent compilation of his published comments on writing interlaced with present-day reflections.

In the book, Mailer tells of how he would trek 40 miles to see Ernest Hemingway—and claimed that writers of his generation and later have never had the same impact. Although one man in the audience protested that he had come from Connecticut and that someone else had flown in from Miami for the event, Mailer nevertheless asserted Hemingway’s primary importance because of his style, “which colored everything for writers after that.”

When a questioner suggested that Mailer and Hemingway shared a certain “swagger” and asked whether it was inborn or developed, Mailer replied that he had started out more timid—like most writers—but that early fame had forced him into the limelight.

Writers who experience such a quick climb enter a position most of us don’t, from which they can write about extreme people and events, Mailer said. But what really gives writers the knowledge they need is what he called “the life you can’t escape,” differentiating it from mere collecting of experience, which carries the freedom to leave at any time. For him, that key, inescapable experience was serving in the Army, a time that he hated but during which he learned more than anywhere else.

—S.H. and J.P.