Ever since 1922, when British archaeologist C. Leonard Woolley discovered the 2,000 burials of ancient Ur, the treasures from its royal tombs have held a lasting spotlight. That dig, a joint venture between Penn and the British Museum, produced stunning evidence of an ancient Mesopotamian kingdom in what is now Iraq. Demand to see those objects peaked after the 2003 looting of Iraq’s museums and archaeological sites, turning a modest tour of the Royal Tombs of Ur exhibition into a 13-venue extravaganza that earned the University almost a million dollars.

But Woolley had to dig his way through a mass of human carnage to get to those treasures: the remains of the soldiers, servants, and several dozen female attendants who died along with their queen. Researchers are focusing now on what these less-glamorous artifacts can tell us about life 4,500 years ago in this Bronze Age civilization. A new exhibit at the Penn Museum, Iraq’s Ancient Past, reveals a surprisingly advanced society, with trade routes covering an entire continent—and a more brutal lifestyle than previously imagined.

It took 12 years and a couple hundred laborers to excavate the royal cemetery, and Woolley wasn’t that interested in the skeletons. “The bones were not well preserved and he didn’t make much of an effort to save them,” says Richard Zettler, the associate curator of the Near East Section who organized the exhibit. After a while, even Woolley’s curiosity about the ornaments of the queen’s many attendants waned. “Everything is going well,” he wrote in a letter. “We are sick to death of getting gold headdresses out of the ground.”

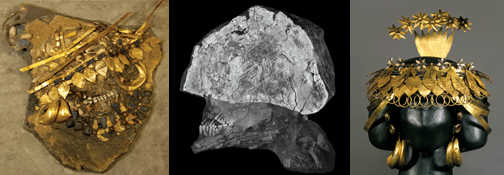

But those bones and headdresses are helping scientists piece together some ancient mysteries. After seeing the Tutankhamun and The Golden Age of the Pharaohs exhibit at the Franklin Institute in 2007, which featured a reconstruction of the king’s head based on computerized scans, Zettler had the idea of CT-scanning the skulls of a soldier and servant found in the royal tomb, flattened by the weight of dirt they were buried beneath. “I thought we might be able to put them into three dimensions and reconstruct the faces,” Zettler says.

Janet Monge Gr’91, a forensics expert and associate director at the Penn Museum, performed the scans at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. To her surprise, they revealed small round fractures on the backs of the skulls, indicating that the queen’s servants had not consumed poison—as Woolley had speculated—but were killed with a sharp instrument. The female servant’s skull showed one blow; the soldier, a robust man in his mid-twenties, required two.

Finding the queen’s female attendants neatly arranged, headdresses in place, Woolley had assumed they went willingly. “He constructed this whole Jonestown or Heaven’s Gate scenario where everyone performed their last rites, drank poison, then lay down to die,” Zettler says.

Despite her shout of surprise when she spotted the fractures, Monge admits mass murder hadn’t been out of the question. “We think of ancient Egypt as being kind of weird, but the elaborate preparation for the afterworld has been around much longer than that,” Monge says. “Royal servants probably didn’t have much choice about their virtual slaughter. They were raised to believe this was the honorable way to die and probably believed they were making life better in the next world.”

A mural at the exhibit’s entrance shows Queen Pu-abi as a glamorous vamp, the way she was depicted during the excavation—evidence of how Ur was idealized in Woolley’s time.

Queen Pu-abi was actually petite, about 40 years old, and wearing 14 pounds of ornament at the time of her death, including a beaded cape and 40 feet of gold ribbon wrapped around her massive wig. In the current exhibit her elaborate funeral garb is shown, for the first time, fully assembled on a life-size mannequin. Piles of lapis beads and gold ornament found beside her have been reassembled into an elegant series of necklaces.

Yet very little of this finery was made in Ur, and virtually none of the materials found in the tombs were mined there. Researchers recently analyzed the gold, lapis, and calcite, among other substances, to trace their sources. A giant map of ancient Mesopotamia covers a wall of the exhibit, showing intricate trade routes reaching all the way from Troy to the Indus Valley, present-day Afghanistan to southern Russia.

The exhibit ends with a note about the tragedy of the looting in Iraq and what it means not only in material loss, but also to the ongoing study of ancient Middle Eastern cultures. Fortunately, the site of the excavation, what was once Ur, was located on an air base and protected from looters. As the current exhibit makes clear, well-preserved artifacts—like the 100,000 housed in Penn Museum’s Near East collection—can continue to unravel mysteries as technology evolves.

“The recent discoveries demonstrate that there is so much more to tell about the queen, the extraordinary death and burial rituals that went on, and the complex system of economic and social relations across that continent,” says Hodges. “There is so much more work to be done.”

–Cathleen McCarthy