Since her nomination to become the University’s eighth president last winter, Amy Gutmann has spent a lot of time quietly thinking and talking with people about how to move Penn forward. Now she’s eager to get to work.

By John Prendergast |Photography by Candace diCarlo

Sidebar |”A Palpable Sense of Optimism”

Talking with Dr. Amy Gutmann a few days after she moved into her College Hall office—the walls still bare after a fresh coat of paint—it quickly becomes apparent that her toughest challenge since being elected Penn’s president was waiting for July 1, and the official start of her tenure, to arrive. Where some might be daunted by the University’s size and complexity, or by the burden of expectations that comes with Penn’s rapid advance over the past decade, Gutmann exudes a positive sense of relief—and not just because, as much as there is to do, it still beats holding down threejobs: “the provost at Princeton, the president-elect at Penn, and making the move” to Philadelphia. “This seems much more normal to me,” she says. “I’ve always liked to work hard.”

Gutmann, an internationally renowned political philosopher and democratic theorist whose work often deals with ways of negotiating highly charged social issues, says her way of leading “is by deliberating with the broadest range of people in the Penn family and inviting them to join with me in furthering Penn’s mission, as I articulate it, and as I make sure we really do move forward very effectively.”

To begin that effort, through the winter and spring, Gutmann traveled weekly from Princeton to West Philadelphia, meeting with former President Judith Rodin CW’66 Hon’04, the deans of Penn’s 12 schools and senior administrators, trustees and alumni leaders, and various faculty and students to discuss the University’s strengths and the challenges ahead, as well as “just getting to know people and having them get to know me,” she says. “One of the pleasures of being at Penn is that there are so many great people here, and great in all senses of the term—dedicated to Penn, full of knowledge and understanding, eager, not complacent, energetic, and wanting to make a difference.” (For how these positive feelings are reciprocated, see page 34.)

As valuable as these meetings were, “I really believe in leading while learning, so my pure learning experience is over,” she adds. “When I arrived here, I was ready to start leading.” Besides continuing to refine the University’s mission and priorities building on the “strong base” provided by the current strategic plan [“Gazetteer,” September/October 2002], Gutmann’s immediate focus is on filling vacancies in several senior administrative and faculty posts and planning the events around her inauguration, scheduled for October 13-15. (For more information, visit www.upenn.edu/inauguration.)

“One of the ways that I am planning the inauguration very personally is to put together a series of panels for a symposium that will be irresistible to our alumni as well as our students—because it will address the challenges that Penn faces in the 21st century,” she says. The symposium, titled Rising to the Challenges of a Diverse Democracy, will bring leading experts together on campus for discussions encompassing the communication of knowledge in an unequal world, how investments in science and medicine can improve lives, ways of educating professionals to be engaged citizens, leading and learning from local and global communities, and making the most of cultural differences.

Rising to a challenge is clearly a theme that resonates with Penn’s new leader. “It’s a delight to be here, and it’s been wonderful to get started,” she says. “July 1st was just a great day.”

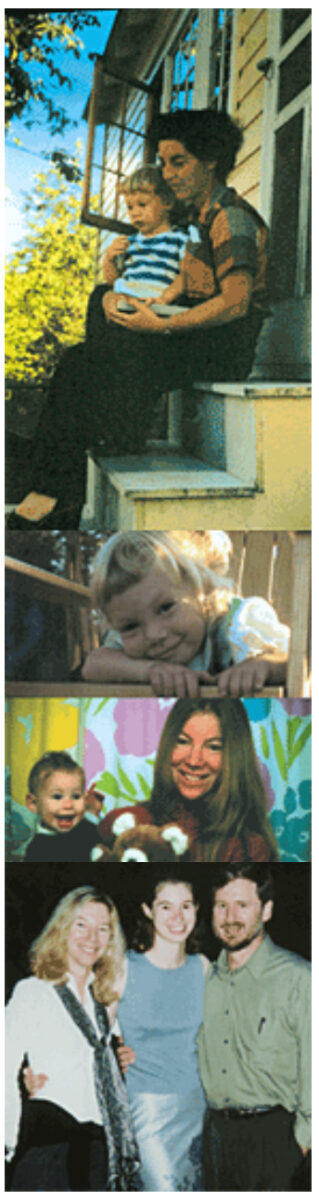

Amy Gutmann grew up in Monroe, New York, a small lakeside community, “very rural” at the time, which except for being about an hour north of New York City was “indistinguishable from the heartland of America,” she says. Her devotion to her parents, Kurt and Beatrice Gutmann, both now deceased, remains strong and apparent, their example a touchstone; at the press conference announcing her nomination, she concluded by saying she only wished they could be there “to know that this has happened, this wonderful opportunity in my life.” She describes them as “extraordinary people with great values” and a powerful faith in America as the land of opportunity—if not entirely for themselves then certainly for their only daughter, to whom they gave “everything a child could hope for.”

Her father was a man devoted to his work and family, who “imparted tremendous strength” to her. In 1939, he took the lead in convincing his relatives to make their escape from Hitler’s Germany, traveling first to India and then to the United States. Her mother was born in America, “a child of the Depression” who always wanted to be a teacher but had to work from the time she was young.

For as long as she can remember, Gutmann shared her mother’s ambition, only changing the level at which she wanted to teach as she moved through the educational system. “When I was in kindergarten, the only thing I remember is that I wanted to be a kindergarten teacher, and then I went to high school and wanted to be a high-school teacher. In college, I wanted to be a college teacher,” she says.

After graduating from Monroe-Woodbury High School, where she was valedictorian, she went on to Harvard-Radcliffe College, initially intending to major in mathematics but eventually gravitating to politics and philosophy. Math always came easily to her—“No one had to teach me,” she says—and she remains attracted to the discipline’s beauty and elegance. Yet she hungered for something less purely intellectual, that engaged more with the world at large.

“I think it would have been impossible for me to know I wanted to be a political philosopher when I was in kindergarten,” she says with a laugh. “Even in high school I was never introduced to a subject matter called philosophy, let alone political philosophy. It was a great challenge when I got to college [to realize] that there was a subject that combined analytical challenge with practical application to the world.”

While still an undergraduate, Gutmann was admitted to a Harvard graduate seminar on justice taught by John Rawls, whose 1971 book A Theory of Justice, which proposed the notion of “justice as fairness,” was both extraordinarily influential among political philosophers and also widely read and discussed. In an obituary she wrote for Princeton Alumni Weekly after his death in November 2002, Gutmann called Rawls “the greatest political philosopher of the 20th century,” possessed of a unique “combination of intellectual genius and moral goodness.” She also credits Michael Walzer, Robert Nozick, and Judith Shklar, scholars of widely differing views who were all then on the Harvard faculty, with helping spark her interest in political philosophy and motivating her “to teach and write about issues of social justice.”

In time, Gutmann saw that her interest in teaching could be tied to an interest in the role of higher-education institutions and how they can contribute to “freedom and opportunity for all humanity,” and that focus has continued up to the present. A major reason she was attracted to becoming president of Penn was the University’s tradition of melding theory and practice, she says, “a way to show how important higher education is” to society.

She followed her undergraduate degree with a master’s in political science from the London School of Economics in 1972 and then returned to Harvard for her Ph.D. in 1976. While in graduate school, she met her future husband, Michael Doyle, a fellow student of political science, and both went on to join Princeton’s faculty. They were married in 1976, and have a daughter, Abigail, now a Ph.D. student in chemistry at Harvard.

Both husband and daughter approve of Gutmann’s new job.

“I’m just delighted,” says Doyle, currently the Harold Brown Professor of Law and International Affairs at Columbia University. “I know that Amy is thrilled, and so is her whole family. It’s a wonderful opportunity for her. We think it’s a great opportunity for Penn as well.”

Husband and wife share a scholarly interest in issues related to democracy, but Doyle’s work focuses more on the international system and how it can be made more participatory, he says. Before moving to Columbia from Princeton last September, he had served for two years as a special advisor to the Secretary General of the United Nations.

He will live in Philadelphia, for now sharing Gutmann’s temporary residence on Rittenhouse Square until renovations to the President’s House are complete this fall, and will keep an apartment in New York for days when he is teaching.

Abigail Gutmann Doyle also plans to make the trip down from Cambridge to visit “as often as I can,” she says. “We definitely try and make time to be [together] as a family even if we’re all doing different things and traveling. I’ve been twice now to the area, and really enjoyed it.”

With both parents on the Princeton faculty, Abigail was born and spent her childhood in the town. She calls it a “great place to grow up,” but says Penn is the place for her mother now. “Just from her personality and how she has grown over the past 10 years, it’s a great job for her,” she says. “She is an amazing people person and able to interact with other faculty members and understand what they want and also understand where students want the university to go. At the same time, she is extremely detail-oriented, which is impressive for someone who understands the bigger picture of things.”

Though she is pursuing a different field of study from that of her parents, she intends to follow them to a career in academe. “I love teaching, and I’ve seen from my parents how much fun it can be,” she says. “You get to prolong being a kid—you’re always learning—and I love the idea of educating other people along with them educating me.”

As for the values her parents instilled in her, Abigail says: “A lot of [what they taught] has to do with the integrity of your personality and how it translates into your work, as well as to your interactions with your friends. No matter what, they have always put their friendships above everything else—their friendship to me, but also to all their colleagues. And it’s amazing how well my mom keeps in touch with friends from her past—and it’s really surprising given what a busy person she is professionally. I’ve always really admired that.”

Even for someone who lets old friendships slide (or doesn’t take on major full-time administrative posts), Gutmann’s scholarly output would be impressive. She’s published more than 100 articles and essays; edited volumes on political philosophy, practical ethics, and education; and published a dozen or so influential and highly honored books. Her most recent include Color Conscious: The Political Morality of Race, which pairs essays written by her and K. Anthony Appiah; Democratic Education, which examines who should have the authority to shape the way citizens in a democracy are educated; Identity in Democracy, a consideration of the “good, the bad, and the ugly of identity politics”; and Democracy and Disagreement and Why Deliberative Democracy? both co-authored with Dennis Thompson, the Alfred North Whitehead Professor of Political Philosophy at Harvard, in which they argue that deliberative democracy offers an approach for resolving some of America’s most trying moral disagreements—and living, on terms of mutual respect, with those that can’t be resolved.

Though her list of research interests reads like a dream lineup for a cable-news shouting match—religious freedom, equal opportunity, race and Affirmative Action, education, democracy, multiculturalism, and ethics and public affairs—Gutmann’s prose is characterized by a calm (though never dispassionate) lucidity and a patient effort to reason through the most intractable issues. In the classroom, colleagues and former students say, her greatest strength is her ability to open a dialogue with students, sharing her views but never imposing them, and drawing out the best from others.

Democratic Education devotes several chapters specifically to higher education. In considering the role of universities in society, she contrasts two views—the first is the well-known “ivory tower”; the second sees the university as a “service station” for society. Both are limited, she says.

The problem with the ivory-tower model is that it fails to engage with the issues of the world, while the service-station model, proposed in reaction to the ivory tower’s perceived irrelevance, results in a loss of bearings, stripping the university of its “core mission of preservation, communication, and creation of knowledge.” Universities do exist to serve society, she says, but they do so “by virtue of what we are and do” rather than by passively fulfilling society’s demands—for example, by turning out the required number and type of workers needed at a given time. To pursue their mission, universities need to create environments conducive to teaching and scholarship, which can include everything from protecting faculty members’ ability to express unpopular opinions to creating safe, appealing spaces for undergraduates to live, she says.

The book also addresses the thorny question of the distribution of higher education—who gets in, where, and why. “Access to higher education is the keystone of what we contribute to society,” she says, and institutions like Penn need to create more opportunities for students from all walks of life to get a university education “to better serve our mission and educate future leaders.”

It’s not surprising that access to education is a highly contentious issue—nearly everyone wants to come to Penn or places like it. “For every wonderful, highly qualified student we admit, we are, unfortunately but necessarily, rejecting some other wonderful, highly qualified student,” she says. “Our job is to put together class after class of students who are as excellent and diverse as can be, where excellence and diversity go hand in hand.”

Though Gutmann’s work has at times been drafted into the so-called Culture Wars, she is a determined conscientious objector in that verbal conflict. She deplores the polemics on both sides of the multiculturalism debate, for example, which give the impression that anyone who disagrees with the writer or finds anything to recommend in the viewpoint being attacked “must be a fool,” she says. “We should think twice before suggesting that anyone else is a fool.” Better to learn from—or at least respect —others’ views.

In an influential paper and two books, Gutmann and Harvard’s Dennis Thompson have elaborated their theory of deliberative democracy as a way to achieve consensus among a welter of competing perspectives in government and other spheres of society. Deliberation offers “a way of moving forward on hard issues,” from health care and education, to confronting AIDS, to crime and punishment, in which “all voices are heard,” she says. “If you engage the perspectives of all of the people whose lives are affected by these issues, it is possible to arrive at a consensus that is defensible,” she says. “Not unanimous, but defensible.”

The losers in such a system are those at the extremes, who don’t get their way, but, if exremists did get their way, “most people’s lives would be miserable,” says Gutmann. “This is in a democracy,” she adds. “If you’re in a dictatorship, the dictator gets his way—it’s usually a him, not always.”

Gutmann’s and Thompson’s ideas about deliberative democracy grew out of a course that they co-taught at Princeton. Their initial plan was to simply rewrite their lectures for the course, “but that proved to be not successful,” Thompson says. Eventually, they developed a working method that in many ways mimics the subject. “We spend a lot of time talking—framing the chapter, trying to see where there are points of agreement and disagreement.” Then one of them does an outline, and the other writes a draft, which they pass back and forth until they are satisfied. “We rarely sat down over a computer and tried to write sentences or paragraphs together,” he notes. “That just doesn’t work.”

While some disputes linger as long as the final draft, he says, “Obviously, we would not have been able to write as much together as we have if we didn’t share basic values. So the process of writing about deliberative democracy itself was deliberative—at least at its best—and argumentative at other times.”

Thompson has known Gutmann since she came to Princeton; in fact, while on the faculty there, he was chair of the search committee that hired her, and chair of the department when she was promoted to tenure. He draws a close connection between Gutmann as teacher and scholar and as administrator.

“She is focused, incisive, gets everything done quickly and on time and without any sacrifice in quality,” he says. But her ability to move “quickly, decisively, and efficiently” is combined with an instinct for pausing “when there is a genuine problem that requires further thought.”

In the classroom, “I’ve been in this business for a long time, and I’ve never seen anybody better,” he says. Though a gifted lecturer, Gutmann’s real strength is in the “extraordinary” way she interacts with students, an approach that carries over to her other responsibilities. “She has always seen herself as a teacher, and I think actually even in things like fundraising and chairing meetings of deans, she’s still in a teaching mode,” Thompson notes. “And for Amy teaching is not just imparting information to other people but interacting—in a deliberative way, actually. Sort of bringing out the best in her students and learning herself as she goes along,” As president, he adds, “I see her as the best kind of teacher, and I think the alumni will appreciate that in her, and it will make her, no doubt, a success, among her other qualities.”

Gutmann was drawn to academic administration in part by the opportunity to “put into practice some things that I have taught and written about,” as well as to make a difference for many people rather than just a few. Having seen what “I can do in leading a smaller institution at the provostial level,” when the opportunity of the Penn presidency surfaced, “it was obvious it would be a mistake not to rise to the challenge,” she says.

Before becoming Princeton’s provost in 2001, Gutmann had earlier served as dean of the faculty in 1995-97 and academic advisor to the president in 1997-98. But she was most closely identified with the University Center for Human Values, which she took the lead in developing and directed through much of its first decade, building a substantial endowment and establishing it as a leading forum for discussion of ethical issues and human values. “This represents what I believe leadership should do—make a difference in the world and engage all different perspectives,” she says.

The idea behind the center was to bring the study of ethics to students, faculty, and the public in a forum that could cut across all fields of specialization in recognition of the fact that “there are ethical issues everywhere,” she says. The center sponsors visiting fellowships; prizes for graduate students and undergraduate theses; programs in ethics and public affairs, political philosophy, and law and public affairs; and lecture series. As an indication of how widely the center casts its intellectual net, speakers have included Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, the novelist J.M. Coetzee, the poet Robert Pinsky, and primatologist Frans de Waal.

Leading and fundraising for the center also taught her the importance of “building a strong base—and never ceasing to build,” Gutmann says. What many in higher education fail to realize—though not people at Penn, she is quick to add—is how dynamic and highly competitive their world has become. The complacent fall behind, “and I have represented the opposite of complacency.” Rather, “I see myself as continually looking for the next opportunity,” she says, citing a favorite Franklin aphorism to the effect that those who love life should not squander time, for time is the stuff that life is made of.

Gutmann’s successor as director of the center, Dr. Stephen Macedo, was also a graduate student at Princeton in the days before it was founded. The center has made a “huge difference” to Princeton’s campus, and has been in large part responsible for creating “an amazing culture of public argument on the largest ethical and moral questions,” he says. “It has enlivened the university, enriched its intellectual resources, and made it a much more exciting place to be.”

Gutmann was Macedo’s dissertation advisor, and he was also a graduate teaching assistant for two lecture courses she taught, on ethical issues in public life and the history of political thought. “They were sort of legendary courses,” he recalls, “ones that students years after leaving the university referred back to as pivotal moments in their education.”

The courses were marked by Gutmann’s “extraordinary clear-mindedness” in bringing large ethical questions from the whole history of philosophy to bear on today’s moral problems in public life and presenting a balanced, multi-sided account of the alternatives—while still advancing her own view “in an open-minded way” and inviting criticism. “I think students appreciate that as well.”

As a dissertation advisor, Macedo credits Gutmann with both helping him think through his chosen topic and framing it appropriately “in order to actually get it done,” he says. “The thing about Amy that makes her an excellent administrator as well as a wonderful academic is that she sees how to get things finished in a reasonable amount of time and she is able to define projects that are doable. She has a wonderful practical sense of the limitations of time as well as great creativity and intellectual depth and an incredible sense of relevance.”

Though he says he was unaware of the opportunity at Penn, Macedo was not surprised that Gutmann would be chosen as president somewhere. Indeed, she was reportedly among the finalists for the presidency of Harvard University in 2001. It was after former treasury secretary Lawrence Summers was named to that post that Gutmann was quoted in the Princeton student newspaper as saying that she did not want to be a university president—a statement she amended last winter to say that what she really wanted was “to be Penn’s president.”

Looking back on the presidential search he headed, trustee chair James S. Riepe W’65 WG’67 recalls how Gutmann’s “strength as a candidate continued to grow as we spent more time with her.” Given Penn’s needs for the next 10 years, “it became more and more clear that, in my view, she was going to be the right person for this next cycle in Penn’s evolution,” he says. “And that we were catching her at the right time in her career cycle—and that’s a very important match.”

Penn Alumni president and trustee Paul Williams W’67, a member of the search committee, recalls that, based on her background and the enthusiasm of her references, Gutmann stood out from the pack from the beginning as an exceptional candidate—an impression that was confirmed and reinforced upon repeated encounters. (He calls the search process “an iterative one, to say the least.”)

“From our first meeting, it was clear that we were talking to an individual who sought the challenge of a complex institution, a large institution in terms of size and intricacy, and an urban institution,” he says, “and that those things together gave the sense that, as she looked at her own career, this could be one of the ultimate challenges that she would aspire to take on.”

With several senior administrative and faculty posts open, Gutmann will be spending significant time this year building her leadership team—a process she started even before her term formally began. “There’s very little that one can do alone that one can’t do better with a great team in place,” she says, “because it just multiplies how much you can accomplish any given day.”

Gutmann’s first hire was her chief of staff, Joann Mitchell, who had been vice provost for administration at Princeton and had worked at Penn from 1986-1993; she also started on July 1. Perhaps not surprisingly—she did, after all, agree to follow her here—Mitchell gives Gutmann high marks as an employer. “She is tremendously supportive, straightforward, and frank,” she says, generous with praise but “not shy when there is an outcome that was less than what she’d hoped for—particularly if she thought you could have done better.”

Having worked at both institutions, Mitchell has a special insight into the differences between Penn and Princeton. Besides Penn’s urban location, larger size, and greater complexity, she points to the University’s “decentralized” structure. Where Princeton has one faculty, Penn’s 12 schools “have a great deal of autonomy,” she says.

Gutmann’s history of forging “respectful collaborative relationships,” which Mitchell calls the “hallmark of her administrative tenures,” will stand her in good stead in managing in this context, she adds. “I don’t think that’s going to as big an obstacle as people might imagine.” Gutmann is also familiar with institutions like Harvard, her alma mater, and Stanford, where she is on the board of its Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, that function along lines similar to Penn’s.

Searches to fill the open positions of executive vice president—held most recently by former U.S. Marines Major General Clifford Stanley, who resigned last October—and the vice president for development and alumni relations—vacant since Virginia Clark left in 2002 and put on hold when President Rodin announced her plan to step down last year—are well under way, with announcements expected this fall. On the faculty side, Dr. Eduardo Glandt GCh’75 Gr’77, dean of the School of Engineering and Applied Science, is chairing the search committee to find a successor for School of Arts and Sciences Dean Samuel Preston, who will return to teaching in December. A committee to search for a permanent provost will be constituted in the fall to replace Dr. Robert Barchi Gr’72 M’73 GM’73, who left for the presidency of Thomas Jefferson University. As interim provost, this summer Gutmann appointed Dr. Peter Conn, the Andrea Mitchell Professor of English, who before that had served as deputy provost.

Gutmann is also reaching out to alumni. A few days after taking office, she sent an e-mail message to some 93,000 alumni for whom Penn has valid e-mail addresses, inviting comments and suggestions on Penn’s future. Responses have included messages of welcome, personal reminiscences, and plugs for favorite programs, as well as complaints about “wrongheaded policy decisions” and rejected legacy applicants. “People have been very frank,” says Mitchell. “It’s been really valuable.”

And Gutmann will be visiting several cities to meet with alumni personally this fall and spring (see list of locations and dates on page 67).

Based on his experience with her, Paul Williams says, those alumni who encounter this president will find a leader who projects “tremendous energy” and establishes an “immediate personal contact and connection”; is intensely focused; is respectful of all the contributions alumni make, whether of their “precious time” or financial resources; and is “deeply committed to the values of diversity.

“The matter of inclusiveness as an institutional value is going to resonate with the new, emerging generation of Penn alumni,” he adds. “The face of Penn has changed and it will continue to change,” with more international students and more diversity from within the United States as well, “so it’s critical that our programs and our outreach communications reflect that—and Amy will be foremost in expressing those values.”

Gutmann calls Penn’s “very strong and loyal alumni base” one of the University’s great attractions. “I will certainly be interacting a lot with our alumni and also doing the kinds of things that I need to do with our students and our young alumni to cultivate their involvement with Penn and to deserve their loyalty.”

This is in keeping with Gutmann’s abiding belief in the importance of academic community. “The idea of Penn being an extended family is something that is very dear to my heart,” she says. “This will be my family, and I intend to interact a lot with it and do everything I can to cultivate the kind of loyalty that is necessary to make us an even greater institution, and I want to start doing that immediately.”

If not sooner.

SIDEBAR

“A Palpable Sense of Optimism”

First impressions of Penn’s new president.

Princeton Provost Amy Gutmann’s selection to succeed Judith Rodin as Penn president drew widespread accolades from her former colleagues at the University’s New Jersey neighbor and from across higher education. Based on their early experiences, Penn’s deans and senior administrators echo that praise, citing Gutmann’s open-mindedness, curiosity, insight, respect for others, and sensitivity to the University’s history and culture.

At Princeton, Gutmann was both the school’s chief academic and budget officer, and her responsibilities extended to managing a multi-million dollar building program—background that will come in handy given Penn’s array of construction projects, the most extensive of which is the development of the postal lands along the Schuylkill River acquired last spring.

“The completion of any successful construction project requires the bringing together of multiple stakeholders and specialists to achieve a grand vision,” says Omar Blaik, senior vice president, facilities and real estate services. “Dr. Gutmann’s track record is illustrative of a leader who has both the grand vision and the steady focus to pull together all the different specialists into one strategy and build something spectacular.”

“Obviously she makes her own decisions, but she does so by reaching out to people and listening to their opinions,” says Wharton School Dean Patrick Harker CE’81 GCE’81 Gr’83. “She really does believe what she preaches on democracy and dialogue—and she practices that with us.”

SEAS Dean Eduardo Glandt GCh’75 Gr’77 had already heard good things about Gutmann from colleagues at Princeton, where about a quarter of all undergraduates are enrolled in engineering. “Of course at this point she is absorbing, and so in a sense it’s early to say—but one has indications,” he says. “She is a quick study.” Within hours after he met with Gutmann, leaving behind handouts and CD-ROMs on the school, “She had read everything and sent some notes to me; she had watched the CD-ROMs and she e-mailed back to me,” he says. “She has been eager to absorb all the knowledge that she needs—and that bodes well.”

Michael X. Delli Carpini C’75 G’75, dean of the Annenberg School and a writer on politics himself, was already familiar with Gutmann and her work before her election as president. (She has sat on advisory boards for Annenberg and will also have a secondary faculty appointment there; her primary one will be in political science.) He calls her a “true public intellectual” who “addresses important issues of democratic politics and does so with a masterful blend of theory, research, and practice. As a result, her work is relevant not only to scholars, but also to practitioners, policy-makers, and citizens.”

When she learned of Gutmann’s nomination, Nursing School Dean Afaf Meleis admits to some initial concern about Princeton’s lack of a nursing program. “It always worries me when we have a new administrator who has not been involved in nursing before—because usually nursing then become vulnerable,” says the plain-speaking dean, who communicated her feelings to Gutmann. “Within days, she came to meet with me—and I give her a great deal of credit for that—and immediately we established a wonderful relationship.”

Meleis also feels a “great deal of resonance” between her own scholarly concerns and her ambitions for the School of Nursing and Gutmann’s thinking and writing. Her focus on issues of “democracy, liberty, equity, getting rid of any marginalization, and giving special attention to diverse populations” has much in common with Meleis’s own interest in “vulnerable populations,” she says—both as related to women’s health and nursing’s traditionally undervalued status as a profession.

On the institutional level, Meleis says she shares Gutmann’s interest in “interdisciplinarity and the connection between the different components of the University, and the importance of making the University an institution of learning that incorporates the principles of equity and liberty.”

Meleis also emphasizes Gutmann’s respect for Penn’s history and culture. “Because of her style of leadership—of being a learner as well as a provider of knowledge—she is taking her time to listen to the different constituents and learn about the culture of this university,” she says. “She is going to respect the culture, respect the history, and use that to foster the best in the different constituents to move us forward in the 21st century.”

In addition to the above qualities, Penn’s new president “brings a sense of humor and a sense of proportion to the job, which I think is indispensable,” says Dr. Peter Conn, the Andrea Mitchell Professor of English, who was appointed interim provost by Gutmann following the departure of Dr. Robert Barchi Gr’72 M’72 GM’73 for the presidency of Thomas Jefferson University. (Of his appointment, Conn says, “I am delighted to have the chance to be a part of this transition,” and responds with mock indignation when asked about any interest in the position on a permanent basis: “John! It would be premature to speculate on processes that have not even begun.”)

Gutmann is also, he says, “exceptionally articulate in enunciating the core values upon which higher education is based. The sense of purpose that she brings, the sense even of vision, is very exciting.

“Penn is a remarkable institution which has made terrific strides in the past decade or two, and I feel around campus a palpable sense of optimism about the institution itself and about the new leadership,” he adds. “I think we are poised to do even more with the extraordinary collection of students and faculty and staff and physical resources that are gathered here on this campus.”

For Conn, a long-time civic booster who “never tires” of walking the city’s streets, Gutmann’s evident enjoyment of her new home is another big plus. This spring, he gave the newly elected president and her husband a walking tour of Philadelphia. “It was delightful to see a person who had clearly found the place she wanted to be,” he says. “Her response to Philadelphia is enthusiastic and very well-informed already, and clearly simply enhances her response to the University.”

Trustee chair James S. Riepe W’65 WG’67 , who headed the search committee that recommended Gutmann for the presidency, says that she is “off to just a great start, and the feedback I’ve gotten both on campus and off campus has been extremely positive.” He adds, “We traded one high-energy president for another one, I can tell you that.”—J.P.