Class of ’86 | On August 29, 2005, Richard Besser M’86 started his new job as director of the Coordinating Office for Terrorism Preparedness and Emergency Response (COTPER) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Two hours later, Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast. Talk about a baptism by water.

“It’s a tough way to start,” says Besser cheerfully, “but it’s also a great way to start, in that you very quickly get to know people’s strengths and weaknesses; they get to know you and they can see you in a pressure situation. And that really was very helpful in getting to know the organization and moving forward.”

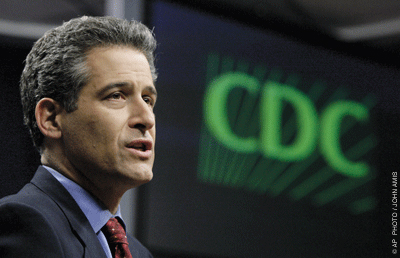

Besser certainly knows the organization now. When we spoke with him this past May, he was all over the nation’s news screens in his capacity as acting director of the whole CDC during another pressure situation: H1N1, better known as the Swine Flu. He didn’t seem fazed by this one, either.

“Under Besser, the CDC seems to be moving with admirable dispatch and clarity to inform Americans and coordinate the government response to the crisis,” noted Time magazine in early May. “He may be the authority figure the nation needs right now.”

Later that month President Barack Obama appointed Thomas Frieden, commissioner of the New York City Health Department, to be the CDC’s permanent director, but he had warm words for the “superb work” of Besser and his CDC colleagues. Under Besser, the Swine Flu preparations at COTPER proved to be “essential,” the president noted. “We are very pleased that he will continue in that role.”

“I was told from the beginning that the administration was only looking at external candidates for the CDC director position,” Besser told the Gazette, adding that “being in a leadership position during the H1N1 response has been an incredible experience.”

That Besser and the CDC have received consistently high marks from the Fourth Estate is another example of careful preparations.

“From Day 1, we’ve had a strategy of very active engagement with the media,” Besser notes. Having seen outbreaks “spin out of control” during the 24-hour news cycle, “we wanted to make sure that if people wanted information, we were going to be there to give it. We have a phenomenal media operation and studio capacity here, and this response demonstrated the real value in that investment.”

Besser comes by his Penn-trained medical abilities honestly: His father, William Besser M’54, is a Princeton-based OB-GYN, and his grandfather, the late Joseph P. Besser M’19, was also a doctor. Through his parents, Rich Besser was introduced to the world of public-health service at an early age.

“When I was in high school, my parents would spend a couple of weeks every summer working on an Indian reservation, and I had an opportunity to go out with them one summer to Fort Defiance in Arizona,” he recalls. “It was a great experience, and I don’t think it’s any coincidence that one of my brothers are I are in public health.”

Before arriving at the School of Medicine, Besser had a pretty good idea that he wanted to get involved in international health issues, based on a high-school exchange year in Australia and a year’s travel in Asia.

“The medical curriculum [at Penn] was really flexible and allowed me to get a block of almost six months at the end of my fourth year,” he says. “I went to northwest India, a town called Manali up in the Himalayas, and worked in a Church of England mission hospital. And it was just an incredible experience—just seeing the quality of health and the dramatic need in the community: vaccine-preventable diseases that were rampant; taking care of a child who tied of tetanus; another who died of whooping cough …”

From Penn he entered a pediatrics residency at Johns Hopkins University Hospital, where he met Dr. Mathuram Santosham, a pediatrician and director of the Health Systems Program at Hopkins’ Bloomberg School of Public Health. Three years later, Santosham hired Besser to work at the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research in Dhaka, Bangladesh, where he studied the impact of acute diarrheal disease on sero-conversion to oral polio vaccine, “to see if there was a problem giving the vaccine to children when they were sick with diarrhea.”

While in Dhaka he befriended one Boris Lushniak, an Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) officer from the CDC.

“I thought he had the coolest job in the world,” recalls Besser, “and I decided that when I came back to Hopkins for my chief [residency] year I would apply to CDC to be an EIS officer.”

Once there, he spent his first two years in the arena of food-borne disease.

“I wanted the group that did the most outbreak investigation, and that was food-borne,” he explains. “Plus, with my experience in Dhaka, I had a natural affinity for studying diarrheal diseases.” (His dinner-table conversations during those years, he acknowledges wryly, were “challenging” for friends and family.)

Besser’s first CDC investigation followed an outbreak of hemolytic uremic syndrome in Massachusetts, and led to the first definitive linkage between unpasteurized apple cider and E. coli poisoning. It turned out to be productive fieldwork on more than one level, as that was when Besser met his wife, Jeanne, a food writer. “I think I have the honor of being the only EIS officer to go out on an outbreak and come back with a spouse,” he says.

All that preparation—which also included stints as epidemiology section chief in the CDC’s Respiratory Diseases Branch and acting chief of the Meningitis and Special Pathogens Branch in the old National Center for Infectious Diseases—would come in handy.

“The principles and the approach that you learn in EIS translates regardless of the type of outbreak,” Besser says. “I’ve worked on anthrax; I ran the Legionnaire’s disease program for a number of years—each of the experiences contributes.”

Besser says he is most proud of the “Get Smart” campaign to educate the public about the overuse of antibiotics and the ensuing microbial resistance. “Building a program with very little money was just a wonderful experience,” he says, “and helped bring attention to what I think is still a very important public-health issue.”

Though the Swine Flu has, as of this writing, calmed down somewhat, Besser cautions that the real test will come when the weather starts to cool.

“We know from the historical analogies of pandemics that the virus can go away, as flu viruses tend to do in the spring and summer, but they can come back in the fall. And this one, should it compete well with other viruses, and should it pick up any virulent factors, would be a big problem.”

By the time this article appears in the Gazette, “we will have been undertaking very intensive planning activities, and community-engagement activities, and preparedness activities,” Besser says. “So should we have to take aggressive action in the fall, we would be ready—and the public would be ready for that as well.”

—S.H.