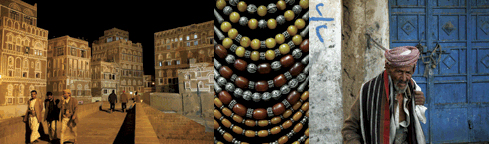

In Yemen, AK-47s accompany lunch.

By Alexei Dmitriev

“It is my duty to warn you: travel in the Yemeni mountains is dangerous,” a uniformed bureaucrat in the Sana’a tourist police told me.

“In what sense?” I tensed up. “One can get robbed? Killed?”

“No—kidnapped,” he said with an intonation meant to make me take the first flight out.

“But people do get released eventually, don’t they?”

“Sooner or later, almost everybody is released,” he said and resumed his cardamom tea.

“And those who are not, do they get killed because the ransom demand was too high?”

“Oh no, the ransom demands are quite manageable. They die in a shoot-out when our soldiers try to rescue them.”

I thanked him for the warning. “But I still would like to get a travel permit. And, if anything happens, please resist the temptation to rescue me.”

The truth is, nobody has been kidnapped in the past few years—since the death penalty for abducting foreigners was introduced in Yemen in 2001. Before then, tourists were sometimes abducted by the tribals to give urgency to a grievance they had with the government: the delay of a school-construction agreed upon in exchange for allowing a pipeline to pass over tribal land, or a couple of tractors that were never delivered to build a promised road. Under these circumstances the kidnapped still enjoyed all privileges reserved for guests. (Tribal hospitality in Yemen is notoriously overwhelming: I heard stories of villagers stoning those who refused to drop in for a glass of qishr, a tea made of coffee husks.) Kidnappers moved hostages from one spectacular location to another, fed them roasted lamb and honey, and entertained them with tribal dances at night. When their release was negotiated after a few days, hostages begged to extend their captivity a little longer, calling it the best cultural-immersion experience they have ever had in any country.

The travel permit is called tasrih in Arabic and one must show it to pass through numerous military checkpoints outside the capital. When a merchant selling old Jewish jewelry at the Al-Milh market heard I was looking for a permit, he sent for his brother, who brought along a friend who had studied in Russia 20 years ago. The next day the friend delivered a much-photocopied piece of paper in Arabic made to look weighty by half a dozen stamps and signatures. The permit identified the bearer as a German consultant with the Yemeni Ministry of Natural Resources. When I reminded him that I was traveling under a U.S. passport, I was mildly reprimanded for being naïve: soldiers at checkpoints read only Arabic and will not ask for a passport. Then I was called a fool to advertise my U.S. citizenship: “You will not be able to leave Sana’a without a military escort. Bush threatened to leave our government high and dry if a single hair drops from an American’s head.”

On my way down to Midan Al-Tahrir to make 16 copies of the tasrih (one for every checkpoint), I was sidetracked by the mouthwatering aroma of grilled kebabs. The smell led me to a hole-in-the-wall where an ancient man was plying his trade. I sat down at the only table next to a fellow in a long coat topped with an unruly sheepskin collar. He muttered bismillah (in God’s name) and plunged into his savory meal. I was soon served a plate of still-sizzling kebabs on a tablecloth of Singaporean newspapers. (Local papers may have Koranic verses that are incompatible with this secondary use.) The man in the coat turned to me, asking, “Tamam, sadiq?” (Is it OK, friend?) Behind his belt he was wearing a traditional jambiya, a dagger that no self-respecting Yemeni man would leave home without. “Tamam!” I replied, with my mouth full. The kebab-seller smiled, fixed the coals with his bare fingers, and tossed me another plate.

Back on the street I passed a group of schoolgirls whose playful eyes shone through the slits in the sharshaf. A whiff of wind lifted their veils on the sides, transforming them into bats flying through the maze of Sana’a’s narrow alleys. The wind also sent flying a pack of the red plastic bags that every purchase in Yemen is wrapped in. The bags gained altitude and rushed outside the city towards Rab-al-Khali (the vast expanse of desert known as the Empty Quarter), where they got caught in the desert shrubs, endowing them with perennial blossoms. I pushed away the thought that the plastic bags might end up traveling farther than these girls ever would.

The next morning the pre-dawn quiet was sliced by allah-u-akbar from a minaret of al-Jama al-Kabir, the principal mosque of Sana’a. God is great. As I thought about the energy of these words that make self-immolation in a crowded Israeli bus an attractive alternative to earthly delights for some, the reverberating declaration addressed to both man and God filled the space between the earth and the sky. Chants from the minarets of Sana’a’s 50 mosques gradually joined in, and in them I heard not so much a call to arms as an expression of religious fervor, at times soft, at times sad, but always personal. The stars could have communicated in this way had they had such powerful speakers.

“My name is Abdullah. I am at your service,” said the driver of a Toyota Land Cruiser picking me up an hour later. I was about to feel omnipotent, because his name means “servant of God” in Arabic, when I saw two more foreigners in the car. Shane, an Aussie, and Gunah, a Malaysian—were “German consultants” with the same ministry as myself.

At the first checkpoint our papers were collected and we were let through. At the second a soldier read them for a while, then disappeared in a mud fortification topped with the Yemeni flag. An officer emerged and launched a monologue that Abdullah summed up for us: First, the first checkpoint is manned by donkey’s children because they allowed nazranis (infidels) to pass; second, we need a police escort when heading north of the capital; and third, we should wait until the officer finds a vehicle and soldiers to accompany us.

Forty minutes later we were racing through the countryside under the protection of a military truck with a turreted high-caliber machine gun and half a dozen soldiers armed with AK-47s. Speeding past all the checkpoints, we braked only for saltah, traditional Yemeni lunch food, in a dusty place called Huth.

Huth was the wild East. At a roadside eatery, machine guns of all types were piled on the tables next to bread and saltah, handguns stuck from under each belt. The protective value of our escort shrank considerably in view of the firepower displayed by the local lunch crowd.

Saltah is a vegetable stew with meat under a greenish fenugreek froth, served in clay pots so hot that the tables were marked by burned circles. A devilish saltah-master in a sweaty tank top ruled on an elevated platform surrounded by a battery of pots and pans spewing up smoke into the blackened ceiling. Waiters screamed orders to an accountant by the entrance, a big guy with a belly. He made a note of the order in a greasy ledger and, with the high-pitched voice of a castrate, shouted instructions to the saltah-master. Suddenly, over the hissing of gas burners, roar of rowdy clients, and screams of waiters, the sound of machine-gun fire came in from the street. Nobody turned or stopped eating. “Long volleys mean it’s joy,” said Abdullah. “Somebody’s getting married or a son is born.”

In 1994 imam Yahya, the religious ruler of Northern Yemen, distributed weapons among the civilian population to resist attacks from Marxist South Yemen. The two Yemens have long united, but Yemenis are in no rush to part with their guns, which explains why an average male owns about six. Twelve-year-old boys run around with jambiyas, expectant of something more powerful when they get older. In the capital one may be asked to show a permit to carry arms, but in the back-country market one can buy pretty much anything: cartridges next to tomatoes, machine guns next to eggplants, a bazooka next to potatoes. Yemenis like their weapons and give them names: Ali—the name of the country’s president—is lovingly reserved for AK-47s.

Still, as calculated by one American sociologist, one is 97 times more likely to be killed in Kansas City than in Yemen. Guns in Yemen are more of a deterrent akin to nuclear warheads during the Cold War: Keep the neighbors at bay. No one relies on the legal system here; everyone can be bought. But not the bullet. Yemenis live like their ancestors 500 years ago: A male is expected to defend the honor of his tribe, his women, his qat, and his well.

After lunch we only got as far as the first qat market. Qat in Yemen is a force second in importance only to Islam. People chew qat leaves wherever they can: in the shade, at work, or behind the wheel, but the most desirable venue is a qat session—a male gathering of friends with qat, water pipe, music, and conversation. The chewed leaves are neither spat out nor swallowed and form a sizable clump of green pulp behind the cheek. Years of chewing have trained a Yemeni cheek to distend to the size of a tennis ball, and in the late afternoon, the male population resembles patients in urgent need of dental surgery.

Yemeni men believe that qat makes them great lovers. During the wedding season, and on Thursdays, when they are most likely to sleep with their women before cleaning themselves for Friday’s prayers, qat jumps in price. A Yemenia Airlines employee whom I befriended once between flights swore that after qat he could make love seven times—but without it, only three.

The soldiers got 2,000 rials from us, bought qat after some quick haggling, and left us surrounded by throngs of armed men. Once the qat sellers realized that nazranis were potential clients, Abdullah had to translate a barrage of juicy offers: “Buy from me—you’ll make love like a lion!” “His qat grows at the cemetery! Mine is like honey with almonds!” “Wash off the dog piss from it first!” They pulled at each other’s kefiyas, or head scarves, and messed about like roguish schoolboys. I forgot that I was a stranger in this land and began to soak up the fun.

Nobody stopped us all the way to Shaharah, although every man we met was armed. This picturesque mountaintop village was conquered only once in the 16th century by the Turks. Today the Shaharis guard the steep and narrow road to the top and make all foreigners take their battered WWII-surplus jeeps with bald tires, charging $10 per person. After a hairy ride, we got off at, as Abdullah modestly put it, the top of the world.

Our home in Shaharah was a traditional guesthouse run by an industrious widow who did not cover her face. She smelled of something exotic and exciting. “It is bakhour, a type of myrrh,” explained Abdullah, eating the widow with his eyes. “Before a night of love, a woman would lift up her skirts and stand over a brazier with bakhour, allowing her clothes and skin to absorb the smell.”

We climbed to a room on the top floor. The afternoon sun shone through the pieces of multicolored glass set in the alabaster windows and turned the walls into a giant kaleidoscope. The carpet was strewn with pillows. Half a dozen men were reclined in the same position: right knee up, left leg bent under, left elbow on a square elbow-rest. In the center was a big tray with three water-pipes, called ma’ada, and a few decanters with qishr. Chewing qat makes one thirsty.

I did not know what to expect from a qat session and just plucked the leaves, putting them in my mouth and sucking on the slightly bitter pulp. A man from across the room threw me a few sprigs and I reciprocated by throwing him some of mine. He said something to Abdullah. Apparently, I had bought the qat favored by truck drivers and would not be able to sleep that night. For the moment, the qat’s effect was slight: the contours of objects got sharper and my fingers were a bit shaky.

After a while I stepped out on the roof for a breather. The sun had just disappeared behind the mountains. Terraces with qat plantations and watchtowers from which Yemenis guard their beloved crop covered the slopes. Two thin crescents, one in the sky, the other on the mosque’s cupola, seemed to be blood brothers. A man carrying a water bucket was walking on a path away from the village. At first I could not understand where he was heading, but then he pulled up his futah and squatted high above the misty valley, leaning on his Kalashnikov. He clearly felt himself at home. His home extended beyond four mud walls to include the rocky tops above, the qat terraces, and the distant valley below. His mission was to protect his home and he was not going to let his guard down. After all, he was a Yemeni tribal.

Alexei Dmitriev G’88 is a native of Russia and documentary maker who lives in Potomac, Maryland. He last wrote for the Gazette about Kolyma, Russia [“Elsewhere,” July/August 2004].