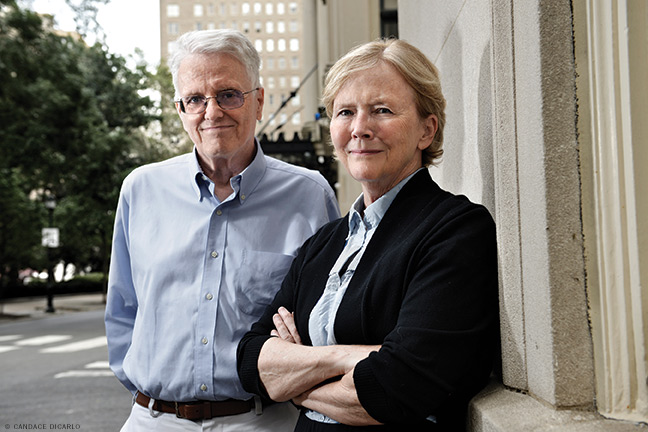

PIK Professors Philip Tetlock and Barbara Mellers have figured out a better way to predict the future. Open minds welcome. Experts, not so much.

By Alyson Krueger

Illustration by Mitch Blunt

On March 17, 2020, California was two days away from becoming the first state to issue a stay-at-home order because of COVID-19. Fewer than 100 deaths from the virus had been reported in the United States and President Donald J. Trump W’68 was still equating the coronavirus to a seasonal flu.

But one US forecasting company—Good Judgment Inc.—was already at work to predict the number of COVID cases and deaths there would be in the next year. Founded in 2015 by two Penn Integrates Knowledge Professors with appointments in the departments of psychology and management who are also married—Philip Tetlock, the Leonore Annenberg University Professor, and Barbara Mellers, the I. George Heyman University Professor—the company had grown out of the professors’ research on human judgment and, in particular, a government-sponsored forecasting tournament in which their global team of non-specialist “Superforecasters” had far outpaced the competition.

“We were forecasting a year ahead,” says Terry Murray, a senior advisor with the company. “This is noteworthy because most other forecasters—including those tracked by the CDC—were only forecasting COVID cases a week or, at most, a month ahead. We literally couldn’t find other public forecasts against which we could compare our forecasts.”

For example, on March 17, 2020, the implied median or midpoint of the group’s forecasts for global deaths as of March 31, 2021, was roughly 2.5 million. The eventual outcome, more than a year later, was 2,818,245. The forecasts were made for a nonprofit organization but available for public consumption.

“People were asking if these forecasts had any use, but these numbers were a big deal in terms of preparing for if this was going to be something like the annual flu in terms of its impact—or is it going to be the Spanish influenza,” says Murray. “If the government had believed our forecasts at the beginning, they would have been preparing for a much bigger thing.”

By the time they founded Good Judgment Inc., Tetlock and Mellers had already spent decades studying what kind of people, and in what scenarios, make the most accurate forecasts of future events. They identified four conditions that help humans make better estimates about what is likely to happen next.

First, the people doing the forecasting must be curious, unbiased, and self-critical. Well-known experts and pundits—the kind of people who publish op-eds in newspapers, prognosticate on cable news programs, and advise organizations from the World Bank to the CIA—often do not meet these criteria, says Tetlock. As his 2005 book Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know? puts it:“Experts are too quick to jump to conclusions, too slow to change their minds, and too swayed by the trivia of the moment.”

The people who do the best job—dubbed “Superforecasters”—are often ordinary people who like to read the news and solve puzzles. “On average they are a bit on the nerdy side, but they are friendly, thoughtful people,” Tetlock says. “The most distinctive quality they have is being openminded. You don’t hear a lot of dogmatic assertions from them.”

The second takeaway is that these Superforecasters are much more likely to make accurate predictions if they work together as a team, rather than alone. “If you let them work together, it’s like a steroid injection,” says Mellers.

Third, even a short training program on topics like how to not let your personal bias get in the way of objective thinking can have a significant impact on accuracy.

And finally, aggregating forecasts ensures that diverse perspectives are taken into account. “We use fancy aggregation methods, but it’s really about collective intelligence,” says Murray. “When people are collaborating, you have different sources of information and different perspectives, and there are things you don’t overlook.”

Good Judgment Inc.’s network of Superforecasters speculates on the world’s most pressing questions for private clients—think multinational banks, government agencies, and sports teams—as well as the public.

You can get a flavor of the type and variety of questions they wrestle with from the Good Judgment Inc. Open Challenge page (gjopen.com), which the company operates as a way of identifying and recruiting new Superforecasters. As of mid-July, open challenge questions concerned the Russia-Ukraine conflict, inflation, the US midterm elections, and challenges sponsored by the Economist on what will happen the rest of 2022 and by Sky News on “political questions of consequence in the UK and beyond.”

“We are like bookies or oddsmakers,” Murray says. “We tell you how likely different options are, just like the weather. Weather forecasters don’t tell you if it’s going to rain. They say there is a 30 percent chance of rain, so then you can decide if you want to take a rain jacket or an umbrella.”

During the pandemic, prominent organizations have publicly announced they were using the company’s forecasts to guide their decisions. Goldman Sachs bought pandemic-sensitive stocks in travel and tourism after reading the Good Judgment Inc.’s forecasts about when a vaccine would be readily available. And the European Central Bank cited the Superforecasters’ predictions during the summer of 2020 that development of a vaccine by early 2021 was increasingly likely in a paper prepared for the January 2021 edition of the ECB Bulletin.

Good Judgment Inc. accurately estimated when Disney’s Magic Kingdom would reopen, when Major League Baseball would resume its season, and whether the Tokyo Olympics would proceed as planned in 2021 after being rescheduled, all events that were hotly disputed.

Superforecasters, who have a specified period of time to make forecasts and can update them before the deadlines as new information rolls in, are currently mulling over the future of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. They put the likelihood that Vladimir Putin will cease being the president of Russia before January 1, 2023, at 3 percent.

Governments including the United Arab Emirates and US military and intelligence agencies have also employed Good Judgment Inc.’s materials in training their analysts. “The more accurate forecasts we provide, the better the government is able to act in response,” says Steven Rieber, program manager at the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA), which supports the US intelligence community. “The effects of Good Judgment’s training program tend to persist. That is unusual.”

“One of the most gratifying parts of my research is that the US intelligence community has taken it seriously and saw implications for changing how they work and [for] improving their estimates,” says Tetlock.

Researching forecasting takes a long time—for one thing, you have to wait for real-life events to transpire to see how accurate predictions were.

Tetlock got his start in the 1980s as a newly tenured professor at the University of California at Berkeley. Then as now, it was a time of great political uncertainty. “People were asking, ‘How is the Cold War going to go? Will there be another arms control treaty? How far will Gorbachev take liberalization?’” he says.

In 1984 he attended a meeting of the National Research Council, the operating arm of the national academies of sciences, engineering, and medicine, where he was part of a committee tasked with using the social sciences to help prevent nuclear destruction. “We realized we had no metric for gauging our proximity to nuclear war, something that had not happened and might not even happen,” Tetlock says.

Yet, that reality didn’t stop many influential folks—politicians, media commentators, government advisors—from making confident assertions about what was going to happen next. “I had always been frustrated listening to the news and listening to the pundits and politicians talk—whose track records were mysterious, but their confidence was great,” he says.

A research question was born. Over the next 20 years, Tetlock studied how successful the “experts” were at making predictions on major world events. He asked 284 professional political observers to answer questions, including whether Gorbachev would be ousted as leader of the then-Soviet Union and if the United States would go to war in the Persian Gulf. He then scored them for accuracy.

His resulting book—Expert Political Judgment—concluded that the answer was, not very good at all. “They are smart people, and they know a lot, but it doesn’t translate very well into forecasting,” Tetlock says. “It’s not that these experts are dumb. It’s that prediction is very, very hard.”

He found that having expertise could actually be detrimental to forecasting—because it makes people set in their views and hesitant to incorporate new ideas and information. “There was an inverse relationship between how well forecasters thought they were doing and how well they did,” Tetlock wrote in his book.

Furthermore, when real life turned out differently than they said, the experts were never held accountable and never admitted they were wrong. “We easily convince ourselves that we knew all along what was going to happen when in fact we were clueless,” Tetlock wrote.

Because the book came out in the aftermath of two high-profile intelligence-related political flops—the failure to prevent the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the unfounded claims about the existence of weapons of mass destruction that led to the war in Iraq—it garnered a lot of attention. “Normally a Princeton University [Press] book doesn’t get reviewed by the Financial Times,” says Tetlock.

“Mr. Tetlock’s analysis is about political judgment but equally relevant to economic and commercial assessments,” wrote John Kay in hisJune 2006 review. “The cult of the heroic CEO, which invites us to believe all characteristics required for great leadership and good judgment can be found in a few exceptional individuals, flies in the face of psychological research.”

“Our system of expertise is completely inside out: it rewards bad judgments over good ones,” stated Louis Menand in a 2005 New Yorker review. A 2010 opinion piece by New York Times columnist Ross Douthat bore the headline, “The Case Against Predictions: You’re better off picking numbers out of a hat than listening to a pundit.”

Trained in cognitive psychology, Barbara Mellers was also on the faculty at Berkeley, where her research focused on a different aspect of human judgment. “I was very interested in models of situations in which people make judgments and decisions that deviate from some kind of normative theory, or what we call rationality,” she says. “Why do they deviate from rational principles and how can we represent that mathematically?” She looked at factors like fairness and cooperation, and how people’s feelings about them influenced their choices.

By the early 2010s, both Tetlock and Mellers were growing dissatisfied with only studying how humans make judgments, they wanted to do something that could make a difference. “I sort of flipped the frame and became much more interested in how to improve people’s judgments and decisions, and what we could do to help them,” says Mellers.

In September 2011, around the same time they joined Penn’s faculty, they were given an opportunity. In an attempt to help the intelligence community improve its performance, IARPA was launching a tournament to see who could create the most accurate, crowd-sourced forecasts.

“The intelligence community may want to know the likelihood that country A will attack country B,” IARPA’s Steven Rieber says. “If we know what a country is likely to do, that might affect whether we engage in diplomacy, whether we need to supply the second country with additional weapons, and so on.”

A recent case in point—and one that suggests the limits of forecasting—is the war in Ukraine. “One of the biggest questions facing us in the last six months was whether Russia would invade Ukraine,” Rieber says. “It would be helpful to have an accurate answer” in a case like that, where many confident public pronouncements were made about why Putin would threaten invasion but not launch a full-scale conflict.

Because forecasts don’t predict an outcome—they estimate the relative likelihood that each possible outcome will occur—an event might happen even if the forecasters believe there is a low chance it will happen. That’s what happened with the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In early 2022, Good Judgment’s Superforecasters thought that the probability of a Russian invasion of Ukraine was below 50 percent. “They were on the wrong side of maybe that time,” says Murray. As part of a postmortem review, Superforecasters provided reasons why they believed they gave the event such a low probability.

“It is always harder to forecast on questions where the outcome is largely under the control of one person. Predicting the thinking, values, and tradeoffs of a group is easier than predicting the decisions of a single person,” said the report. “Going forward, we will work to remain epistemically humble about what one can possibly know about a single actor’s thinking.”

Tetlock emphasizes that forecasters don’t have to have an exact idea of what will happen in order for the information to be useful. As with the weather and betting, paying attention to the percentages is key.

“If analysts had said there was a 75 percent chance that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction in 2003, no one knows how history would have unfolded,” he wrote in Expert Political Judgment. “Better calibrated probability assessments would have lent some credibility to claims of reasonable doubt.”

As the tournament was designed, five teams would compete for a period of four years. Groups of volunteers answered questions like “Will North Korea launch a new multi-stage missile before May 10, 2014?” or “Will there be a violent incident in the South China Sea in 2013 that kills at least one person?” and the teams would aggregate responses and report to IARPA each morning at 9 a.m. each day the tournament was in session.

“It was so interesting because the questions were all over the map,” says Mellers. “There was no way that any single person could have been an expert at all these different topics. Everybody was confused about something.” Each team’s academics and forecasting experts studied how well their volunteers did and implemented interventions that they felt could improve its accuracy scores.

The Penn team, named the Good Judgment Project, was led by Tetlock and Mellers and also involved faculty including machine learning researcher Lyle Ungar, a professor of computer and information science, and Jonathan Baron, a professor of psychology whose work focuses on decision-making. From the get-go, Penn’s team outperformed every other competitor. In the first two years, the Good Judgment Project beat the University of Michigan by 30 percent and MIT by 70 percent. Penn’s forecasters even outperformed professional intelligence analysts with access to classified data.

“We had a control group who made forecasts with no special additional elements beyond the so-called wisdom of the crowd,” says Rieber. “The Good Judgment Project outperformed them.” After two years IARPA dropped the other teams and focused solely on funding Penn’s work.

According to Murray, other teams came into the tournament with a preconceived idea of what worked, like a prediction algorithm, or only using volunteers that had expertise. The Good Judgment Project, however, mirroring what Tetlock and Mellershad learned worked with forecasters, started with an open mind, creating 12 experimental conditions to see what worked.

For example, Tetlock and Mellers wanted to explore collaborative versus individual methods. To attract volunteers at the outset they reached out through professional societies and networked with influential bloggers and others who could advertise the opportunity. Once the tournament had started and generated attention, volunteers reached out to Good Judgment Project to get involved. Some volunteers were assigned randomly to work blindly by themselves, others to work by themselves but with access to comments and notes from others, and a third group to work as a team.

“The teams ended up working [best], but it wasn’t obvious at the beginning,” says Murray. “You’ve heard of groupthink. We weren’t sure if teams wouldn’t just be jumping off a cliff together.”

The Good Judgment Project also looked at the impact of training and found there was a 10 to 12 percent improvement in accuracy after an hour’s worth of instruction. “Foresight isn’t a mysterious gift bestowed at birth,” wrote Tetlock in Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction, a book he coauthored after the tournament that became a New York Times bestseller. “It is the product of particular ways of thinking, of gathering information, of updating beliefs. These habits of thought can be learned and cultivated by any intelligent, thoughtful, determined person.” It is telling that a commitment to self-improvement was the strongest predictor of performance.

The four years passed quickly as the Good Judgment Project team continued to further refine its winning formula. “It was so exciting,” says Murray. “We were just trying all these different things and learning by doing. We doubled down on what worked, jettisoned what didn’t, and kept improving.”

“It was especially fun to win,” says Mellers. “There were about 25 of us around Philadelphia working on the project, so we had a big party at our place.”

“I would love to do it again,” she adds.

After the tournament concluded and Tetlock’s book came out, businesses, especially in the financial sector, approached to ask if the Good Judgment Project group could do work for them. The commercial arm, Good Judgment Inc., was set up in 2015.

Many clients are looking for forecasts on issues that affect their bottom line. “Finance is used to living and dying by making bets on what will happen,” says Murray. “Now we can help them. For example, before the 2020 presidential election we had clients ask, ‘If Biden won, what are the chances the corporate tax rate would go up?’”

Clients also ask Good Judgment Inc. to set up forecasting competitions for them, in order to crowdsource answers from their own people. For example, last year the company helped the British government launch an internal forecasting tournament named the Cosmic Bazaar. “Cosmic Bazaar represents the gamification of intelligence,” noted an article in the Economist about the initiative. “Users are ranked by a single, brutally simple measure: the accuracy of their predictions.”

When Wharton People Analytics organized a conference on the future of work held last April, organizers approached Good Judgment Inc. to help develop a survey for participants. They focused on four questions: How many part-time workers will there be in the US in February 2023, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics? How many job “quits” will the BLS report for that month? Will legislation raising the US federal minimum wage from $7.25 an hour become law before March 1, 2023? Will employees working from home be allowed to itemize deductions for home office expenses before that date?The forecasts will be revisited in spring 2023 to see who was correct.

“We thought it was appropriate that at a future of work conference we would collectively speculate on the future of work,” says Cade Massey, Practice Professor and a Wharton People Analytics faculty codirector. “It also makes the talking more credible. It’s OK to speculate, and it’s fun to speculate, but when you are asked to write down what you think will happen, and you hold onto it and revisit it in a year, all of a sudden you might be a little more thoughtful about what you say. All of a sudden you might do a little research. It elevates the conversation.”

(In the meantime, the questions have also been posted on Good Judgment Inc.’s open challenge page, where the odds for a bump in the minimum wage and allowing itemized deductions were both running at 10 percent in late July; while the most popular range for the number of part-time workers was between 26 and 27 million and for resignations 3.5 million to 4 million.)

Though they remain as cofounders, Tetlock and Mellers have offloaded the day-to-day running of Good Judgment Inc. to concentrate on their ongoing research.

Mellers is looking at issues that emerged from the tournament, such as the fact that some teams thrived while others didn’t. “Sometimes they worked really well, and sometimes they were horrible. They met once or twice, and it fell apart,” she says. “Now I am studying what predicts when teams will function well and work together as a group.”

One early result was that groups tend to thrive if the people who emerge as leaders are both accurate and confident. “If confidence was appropriately lined up with knowledge that was good,” Mellers says. “Groups went off on crazy detours when confidence was negatively correlated with accuracy.”

Tetlock is still on the quest to further improve human forecasting. For example, in May 2022 he helped launch the Hybrid Forecasting-Persuasion Tournament. It is bringing together experts and Superforecasters to predict early warning indicators of serious crises. They are looking at questions in the areas of artificial intelligence, biosecurity, climate change, and nuclear war over timelines of three, 10, and 30 years.

Tetlock hopes his research will impact pundits, politicians, and experts who are still making unsubstantiated and wrong forecasts about the future.

“In my ideal world, in this midterm election I would hope people would be more transparent about the claims they are making, and the policies they are advocating,” he says. “It’s not a sign of weakness to admit you aren’t a good forecaster. It’s a sign of being thoughtful—because we know how they can get better.”

Alyson Krueger C’07 writes frequently for the Gazette.