“I am usually rather bored with definitions,” Stefan Sagmeister wrote on a wall of the Institute for Contemporary Art. “Happiness, however, is such a big subject that it might be worth a try to pin it down.”

When viewing The Happy Show, Sagmeister’s dazzling exhibition at the ICA, it’s important to remember that he’s a graphic designer, and an immensely talented—and provocative—one at that. Forget the album covers for David Byrne and Lou Reed. Sagmeister once had an intern carve words into his skin with an X-acto knife in order to “visualize the pain that seems to accompany most of our design projects.” The photo of his scarred, naked torso became a poster for the Detroit AIGA (the professional association of design).

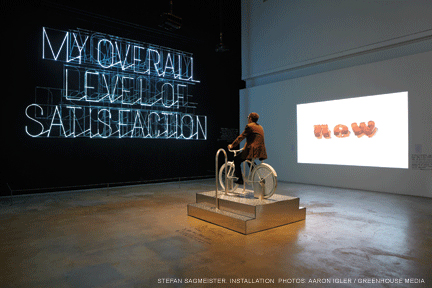

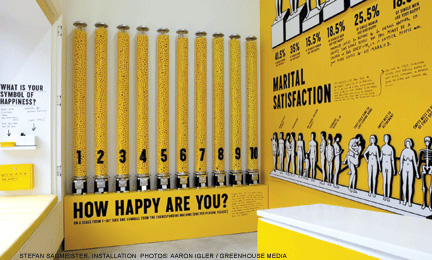

The Happy Show’s individual components are less wince-inducing but equally attention-grabbing, with messages that range from the didactic (KEEPING A DIARY SUPPORTS PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT) to the wryly observational (Trying to Look Good Limits My Life). To get his messages across he uses everything from short films with words that burst into flames, to posters made from bananas, to a row of massive gumball machines, to giant inflatable monkeys. Visitors can pedal a painted stationary bicycle that powers a series of neon signs—which proclaim, in bold letters and different colors: ACTUALLY DOING THE THINGS I SET OUT TO DO INCREASES MY OVERALL LEVEL OF SATISFACTION. SEEK DISCOMFORT.

“Surprise, I think, is a very valid strategy in communications,” Sagmeister told curator Claudia Gould (the former ICA director and current director of the Jewish Museum in New York) during a public interview at Kelly Writers House last December. “And specifically, if you are talking commercial communication, that often has to work in a second or two”—which is one reason why “so many artist-designed billboards are awful, because they don’t understand this, and they wind up saying nothing.”

But The Happy Show does more than just grab eyeballs. It draws on scientific research about happiness (some from the positive-psychology movement, whose roots are at Penn); it engages the mind; it resonates.

Both the exhibition and the still-in-progress Happy Film (a 12-minute clip of which can be viewed at the exhibition) focus on Sagmeister’s personal quest for happiness as well as the implications for humankind. Asking whether it’s “possible to train my mind in the same way I can train my body,” he is exploring three pathways: meditation, cognitive therapy, and psychotropic drugs.

Meditation appears to have been a mixed bag for Sagmeister, who traveled to Bali with his film team for a three-month meditation program.

“I gave it the best shot that I could,” he said. “There were times when I thought this was the best thing ever, and why does not everybody do this? And then there were times when I was utterly bored and very happy at the end of the 45 minutes.” He was still waiting to see the results of an fMRI scan that would indicate whether meditation had had any measurable effects on his brain.

Next was cognitive therapy, which Sagmeister has been exploring with a “great” therapist in New York—who helped him overcome, among other things, his fear of confrontation. (“She’s very practical,” he said. “She’s seen hundreds and hundreds of people, and there’s probably only a dozen archetypes out there. I am a big believer that I overestimate my individuality.”) Trying to Look Good Limits My Life (photos from a 2004 installation) turns out to be about Sagmeister’s desire to “look good” by not being the “bad guy” in a confrontation. Having read “maybe three dozen” positive-psychology books in preparation for the film (including one by Martin Seligman Gr’67, the Zellerbach Family Professor of Psychology at Penn and director of the Positive Psychology Center), his “clear favorite” was The Happiness Hypothesis by Jonathan Haidt, a University of Virginia psychology professor who became the film’s scientific advisor.

While he had yet to explore the psychotropic route to happiness, Sagmeister said that, based on his conversations with scientists “on both sides of the discussion,” he didn’t expect that antidepressants or other drugs would provide much of an edge in the long run.

Kenneth Goldsmith, an adjunct professor of English at Penn who taught a creative-writing class with Sagmeister last fall, called him a “pedagogical dream.”

“He’s spawned countless arguments and conversations, taking us into nooks and crannies, into just about every artistic discipline,” said Goldsmith when he introduced Sagmeister and Gould at the Writers House. Unlike most graphic designers, he added, Sagmeister’s “graphical masterworks are an invitation to leap off the page and enter into the difficulties of interpersonal relationships, weaving together politics and poetics in this sort of meta existential search for happiness.”

—S.H.