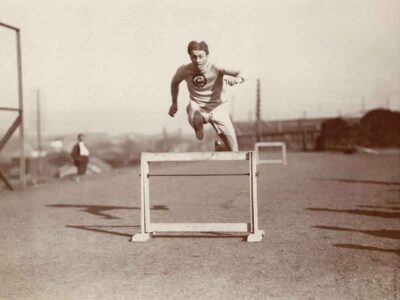

How the Penn Relays is boosted by its distinctive Jamaican flair.

If you’ve been to the Penn Relays, you’ve undoubtedly seen Jamaican athletes sprinting around the Franklin Field track and Jamaican fans happily singing and screaming in the stands.

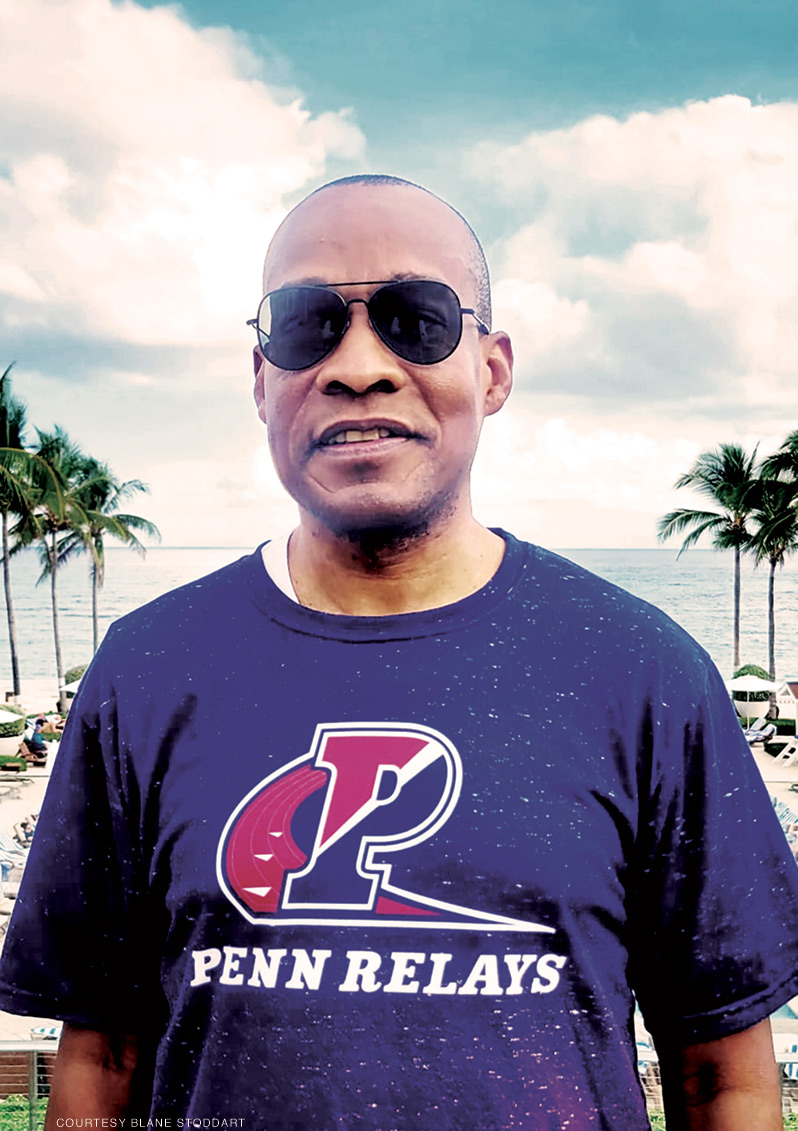

For several decades, Blane Stoddart W’87 has helped give the country’s oldest and largest track and field competition that dynamic Jamaican sparkle.

When the Penn Relays holds its 129th running this April, it will mark Stoddart’s 30th year as a participant. He won’t be there running, jumping, or throwing. Instead, he’ll once again team up with Team Jamaica Bickle (TJB), a charity organized by expatriate Jamaicans and West Indies natives that has helped thousands of student-athletes of modest means travel to Philadelphia to compete since 1994.

A Jamaica native, the 60-year-old Stoddart is TJB’s cofounder and pro bono director of its Philadelphia chapter. His full-time job is running the construction management company BFW Group.

According to Stoddart, Team Jamaica Bickle provides meals, lodging, and local transportation each year to upwards of 500 athletes and coaches arriving from Jamaica and six other Caribbean countries. At the 2024 Relays, there were nearly 700 men and women under TJB’s care.

Besides food, transportation, and hotel rooms, TJB provides opportunities for Caribbean athletes to network with US college coaches and demonstrate their track and field skills that sometimes lead to college scholarships. “We don’t keep an exact count of all the scholarships offered,” Stoddart says. “But after 30 years it’s certainly in the hundreds. Ten to 20 a year is normal. Or put it this way: if we hear only about two or three scholarships, that’s a disappointing year.”

Over the years, high schoolers from Jamaica, Trinidad, and other track-mad Caribbean nations have indeed leveraged strong performances at the Penn Relays into four-year degrees that have returned them to Franklin Field as college athletes, or even later as coaches. Many have gone on to naturalize as US citizens and enjoy careers in medicine, engineering, academia, and the arts.

Stoddart’s passage to Team Jamaica Bickle—the word is Jamaican slang for a picnic or potluck dinner—began as a high schooler, when he emigrated from Jamaica’s Spanish Town district. After graduating from Philadelphia’s Martin Luther King High School, where he was the 1982 valedictorian, he matriculated to Wharton, studying marketing and economics in expectation of becoming “a big Wall Street trader.”

For a while, New York was home as Stoddart worked as a foreign currency options broker. But ultimately he returned to Philadelphia and shifted toward community improvement work, in 1991 becoming CEO of The Partnership Community Development Corporation, catching a wave of urban renewal west of Penn’s campus. He focused on affordable housing, collaborating with Penn’s efforts to improve safety and real estate values in University City. Stoddart’s team helped add some 300 new housing units to the community.

This was in many ways a continuation of Stoddart’s undergraduate years, when he impressed faculty with his volunteer anti-poverty work. “He was my student in the 1980s,” recalls Ira Harkavy C’70 Gr’79, founder and director of Penn’s Netter Center for Community Partnerships. “He has always had a deep commitment to making a difference and contributing to a better community.”

That commitment has manifested with Team Jamaica Bickle, which has helped the Penn Relays flourish, both as an athletic showcase and as an opportunity for Caribbean natives in West Philadelphia to support their homelands’ young athletes. Some expats who help TJB raise money—over $3 million since 1994—are also Penn employees. In TJB’s early years they often welcomed athletes into their homes near campus. Among those hosted: star sprinter Usain Bolt, who made his Penn Relays debut as a high schooler in 2003, before returning to the meet in 2010 as an Olympic champion.

During the Penn Relays, the Palestra becomes the command center for Team Jamaica Bickle, hosting a cafeteria for athletes as well as massage services, music, and meeting spaces for teams arriving from seven Caribbean nations. Nearby on Shoemaker Green, Caribbean food truckscater to diaspora fans arriving from as far afield as Miami and Toronto. And inside and outside Franklin Field, Jamaicans wave their country’s flag, blast air horns, and add jubilant cheers to help turn the track meet into a true carnival [“Penn Relays at 125,” Jul|Aug 2019].

Each April, Caribbean track fans flock to Franklin Field by the thousands. Sprinters from Jamaica dominate many events, especially in high school competition, both male and female. And many Jamaicans remain fiercely loyal to their own high schools’ track programs, even decades after graduation.

That led Rainford “Perry” Bloomfield WEv’07 G’14 LPS’16 SPP’19, an IT specialist at Penn, to launch another charity, called Fortis & Friends, to provide TJB with bus transportation and shuttle service to Franklin Field. “These are life-changing opportunities for these athletes,” Bloomfield says.

Bloomfield is a graduate of Jamaica’s prestigious Kingston College, which in 1964 became the Caribbean’s first high school to send athletes to the Penn Relays. One of them, sprinter Lennox Miller, went on to medal for Jamaica in the Olympics in 1968 and 1972. His California-born daughter, Inger Miller, captured Olympic gold for a USA relay team in 1996, making them the first father-daughter duo to win Olympic track and field medals.

Seeing Jamaicans descend on Franklin Field year after year is especially meaningful to Penn assistant track coach Chené Townsend, who competed at the Penn Relays for Kingston’s Convent of Mercy from 2006 to 2009. Townsend recalls the familiar aroma of TJB’s food helping her relax during her first visit to University City. “Just creating a space that feels very safe and very comfortable is so important,” says Townsend, who was 16 when she made her Penn Relays debut. That began a journey to West Virginia University, where she met Shelly-Ann Gallimore, another Penn Relays veteran from Jamaica, who became her college coach and mentor.

Stoddart notes that a similar Penn Relays connection has enriched him for decades. “I was still in my teens, a kid born in Jamaica and just out of high school, when Penn changed my life,” he says. “All these years later, thanks to the Penn Relays, I’m still fully engaged with the island, and pushing other teens to find their futures.”

—Joel Millman C’76