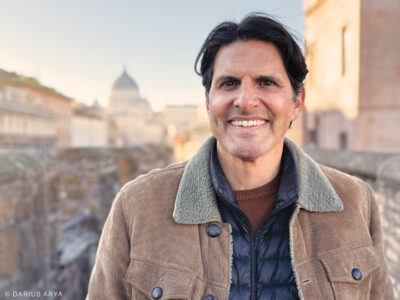

When David Gilman Romano Gr’81, a senior research scientist in the Penn Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology’s Mediterranean section, signed on to excavate the Sanctuary of Zeus on Mount Lykaion, he expected to find evidence of early worship to the Greek god of thunder. What he didn’t expect was how ancient that evidence would be.

Since 2004, Romano and the Greek-American research team he co-directs have found objects on Mount Lykaion that date “from B.C. to B.Z.—Before Zeus,” he joked during a recent lecture at the Penn Museum.

The depth of these discoveries may not be surprising, considering that the site—a 4,500-foot peak in the Peloponnesus region of Arcadia—had not been excavated since the early 20th century, long before the existence of radar, remote sensing, and ground-penetrating magnetometry.

With the aid of these advanced techniques, the archaeologists have uncovered objects from Mount Lykaion’s ancient altar that date back to 3000 B.C.—about 1,000 years before the Greeks began to worship Zeus. These findings “suggest that the tradition of devotion to some divinity on that spot is very ancient,” Romano said.

This remarkable discovery —a collaborative project of the Greek Archaeological Service, 39th Ephoreia in Tripolis, the Penn Museum, and the University of Arizona—has left many questions in its wake. In particular: If Zeus wasn’t around yet, who was being worshipped on Mount Lykaion some 5,000 years ago, and by whom?

“We don’t yet know exactly how the altar was first used in this early period from 3000 to 2000 B.C.,” Romano said. His team is currently exploring possibilities, though, including use of the altar in connection with wind, rain, earthquakes, or other natural phenomena.

For ancient cultures to link the site to natural forces would be unsurprising, given the unusual weather patterns in the region and the altar’s placement between three fault lines. “Many of us who have worked at Mount Lykaion … have experienced the fury of summer storms on the mountain, and we have witnessed the absolutely amazing lightning that occurs in the area,” Romano said. He recalled a July day on the mountain that began at a hot, humid 100 degrees. In the early afternoon, “the clouds gathered, it began to rain—thunder and lightning,” he said. “Then the rain turned to hail, and by 5 in the afternoon … the ground temperature was in the low 40s.”

Indeed, the god famous for wielding a lightning bolt was also referred to in ancient texts as “Cloud Gathering Zeus,” “Master of the Bright Lightning,” and “He who Releases Rain.” What’s more, the very name Zeus originally signified sky. Knowing this, experts have suggested that Mount Lykaion may eventually reveal the origins of the Greeks’ devotion to the powerful god.

While they work to discover who or what was worshipped at the altar B.Z., Romano and his team continue to explore other areas of the ancient mountain. In addition to its altar, Mount Lykaion was “famous in antiquity for its Pan-Arcadian and Pan-Hellenic athletic contests in honor of Zeus,” Romano said. To investigate these ancient games, Romano’s research team has excavated the site’s ancient hippodrome—an open-air stadium with an oval course for horse and chariot races—that Romano said is the “only example [of a hippodrome from] the Greek world that can be visualized in the modern day.” So far, the team has discovered ancient starting-line blocks, pottery, coins, and metal fragments that will help them date the area.

In addition to detailing his findings, Romano paid tribute in his lecture to the residents of Ano Karyes—a small village in the eastern slopes of Mount Lykaion—who have aided his team members over the last four years.

“Its winter population is only 23, but the village has supported our project in every imaginable way,” he said. The townspeople have turned over their cultural center to Romano’s team for use as a research laboratory and project center, and have also offered space in a private house for the team to eat all their meals.

As part of their project, Romano’s team has developed plans for a 300-square-kilometer archaeological park. “The idea of this proposal is to unify and protect the ancient cities and sanctuaries in this part of the Peloponnesos,” he said. “The proposal would include the creation of roads and trails to connect the ancient cities and sanctuaries … and support the strengthening of the infrastructure of the area to protect against the kind of ravaging forest fires that occurred in this area last summer.”

While his team’s plans and discoveries have garnered much attention, Romano admitted that the publicity can be jarring at times.

“One of the interesting things about the digital age we live in is that we can read about our work and our discoveries virtually at the same time that we are thinking, speaking, and writing about them,” he said.

Yet in some ways their exploration has only just begun. “After four years at Mount Lykaion … we have literally only scratched the surface,” Romano said. “We hope that our continuing excavations in the altar will shed further light on the origins and development of the cult of Zeus.”

—Molly Petrilla C’06