Every time I moved, I was faced with the prospect of reinventing myself.

By Ami Dalal

Even more so than our parents, whose memories are firmly planted in the India of their childhood, the children of these immigrants are torn between two worlds. One consisting of our parents’ mild hysteria that the motherland not be forgotten: panicked anecdotes peppered with yearly visits to India, forced dress-ups for Diwali parties, awkward introductions to every Indian family in the postal code, and sullen Sunday mornings listening to bhajans at the local temple. The other is an unspeakable longing to fit in with the kids and the culture we grew up with—a craving for ranch dressing and onion rings, beers surreptitiously sipped at rock concerts, sagging pants, slouched shoulders, and the leggy soccer guy we’d take in a hot second over that next-door-Sanjay whose good grades are something our mothers think is a selling point to us.

As the daughter of two Mumbaikars, I was born in the United States and have spent most of my life as an expatriate, shuttled every three years to another country because of my father’s job. My childhood stint began in the countryside of Belgium, followed by a monotonous three years in suburban Houston, a plunge in the equatorial blip of Singapore, rounded off by a temperate spell overlooking the mountains of Venezuela. A constantly evolving identity is what I—the offspring of roaming immigrants—had to contend with. I watched the Bollywood flicks that my parents rented from the local Indian grocer, and on the weekend traipsed to art festivals to watch Amélie with my new beatnik friends. I had one foot tapping out a beat from Missy Elliot’s latest hip-hop album, and another twirling loose-hipped to the saucy lyrics of salsa queen Celia Cruz.

Each time I moved to another international school, I was faced with the prospect of re-inventing myself, of being magically presented with the opportunity to move up the adolescent food chain. Personality, interests, mannerisms, clothes, hair, shoes, backpack—everything was up for renovation. It was like the middle-school version of American Idol, and maybe this time I’d hit the jackpot and become the overnight new-girl sensation.

Like a veteran, I’d reel off the schools I’d been to on the expatriate circuit. I learned to recognize the four main breeds, in descending order of who moved the most: the army kids who had coveted access to military stores that sold imported Doritos and Seventeen magazines; the embassy kids whose diplomatic license plates granted them immunity from local police; the multinational company kids who had the perks of drivers, maids, and homes in the most affluent areas; and the permanent kids whose foreign parents had started their own company or married a local spouse. Nationality, ethnicity, and background were unimportant—we came from everywhere and nowhere at the same time—and we needed each other to build roots as quickly as possible after being plucked from the last place we remembered was home.

I accepted the uncertainty that my best friend could be in Jakarta by the end of the week, that being stranded without a back-up best friend was equivalent to social suicide, and that my group could fragment with the massive yearly influx of new students. Seasoned expat kids forgot how to miss people, and now, as adults, we’re still blamed for an inability to become deeply attached. Sometimes old friends crossed paths. I bumped into a childhood friend from Belgium seven years later when I was changing in the locker room of the Singapore American School. When she left, we lost touch again.

No city felt quite like home, but I had grown to love bits and pieces of each one. I looked Indian but felt more comfortable speaking Spanish on the streets. I preferred drinking flavored soybean milk to Coca Cola and had never lost the Belgian habit of eating French fries with mayonnaise. Like a nesting bird, I carefully hoarded fragments of memories, smells, sounds, and habits from each place of residence. But when I arrived at Penn and was no longer defined by the number of cities I’d lived in, I was at a loss as to how to fit the pieces together. Negotiating my own identity—which had traveled through four continents and grown roots in none—was like navigating a Thesean labyrinth or trying to assemble one gigantic puzzle from dozens of boxes.

I didn’t fit in with the Indian kids who strongly labeled themselves as South Asian; I didn’t belong with the international students who had grown up in their home countries; and I didn’t even feel American even though I held a U.S. passport. Though I was repeatedly asked where I was from, no one understood that I didn’t have to be from anywhere or identify with anyone. I had grown up in schools where the range of nationalities ran the breadth of the United Nations; it was implicit that home was as relative a concept as time or space.

I often felt the equation at Penn was too simplistic. Students seemed to pigeonhole themselves into monochromatic categories like ethnicity, extracurricular interest, or fraternity alliance. Identity was far more complex, far more fragmented, and far more slippery a concept to have its boundaries outlined by nationality or pastime. Many times during my four years at Penn, I felt like an outsider and deeply ached to go home—but where to? Home was transitory, I was a transient, and it was too late to return to the multiethnic, multi-tongued, borderless safe houses of expatriate schools.

After graduation, confused about my career and myself, I reacted the only way I knew how: I moved again. I decided upon a place I hoped would answer my questions of roots, identity, and belonging. After 10 months in India, I again felt like an outsider. I bucked against the conservatism expected of women; I fumbled with a language that rolled clumsily off my tongue; and I fiercely missed the individualism of the United States. After I received an employment offer from the top newspaper in New Delhi, a visa officer accused me of taking jobs away from Indians, hinting that I should repatriate immediately.

By then, I had worked for four months in a village in earthquake-prone Gujarat. Eighty percent of India’s population lives in rural areas, and my exposure to their lives was more comprehensive than that of most city folks who never ventured far beyond their air-conditioned homes, chauffeured cars, and cinema multiplexes. Yet the country still felt foreign to me, and I had answered none of my questions of identity and home.

On a Saturday morning, I sat down to write my first assignment about the children of the Indian Diaspora, but stopped short. Before I could write about the lives of millions of young people, I had to first define who we were and who I was. I had learned to fit into whatever world I inhabited without making a ripple; now, at 22, it was no longer a question of fitting in, but rather one of untangling an unruly mop of loyalties and braiding them together again as neatly as possible.

I was torn between my allegiance to my parents’ world and the countries I had lived in, but I realized the choices were not mutually exclusive. Though it was confusing to straddle different cultures, the options to forge my own identity were limitless. Far removed from geography, from citizenship, and from sepia-toned memories, my identity’s foundation rested upon my parents and older brother and what is unchangeable in my character—which, off the top of my head, consists of a tablespoon of impatience, a pinch of moodiness, and a dash of daydreaming. Like the primary shades of a color wheel or a Rubik’s cube, these fundamental elements combine in innumerable permutations depending upon where I am living, what I am doing, and whom I am spending time with.

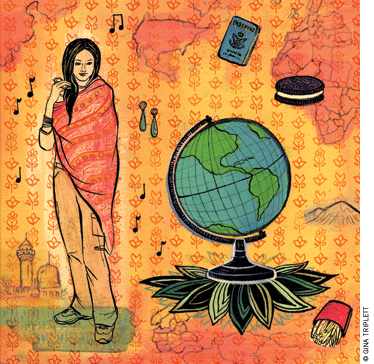

I realized that identity for me—the daughter of immigrant nomads—was something I must manufacture myself. I could customize my identity as easily as a Dell computer, a freedom that my parents never had. I put down my pen, closed my notebook, and decided to take the rest of the day off. I threw on a Kashmiri shawl with camouflage cargo pants and jade earrings, snapped on the headphones of my iPod nano and turned it to the merengue beats of Juan Luis Guerra and the classical ghazals of Ustad Khan, and grabbed a saffron-sweet popsicle and a handful of Oreos on my way out the door. Not one color, sound, or taste really matched, but who was keeping count anyway?

A compulsive mover, Ami Dalal C’05 W’05 hopped on the first plane she could find after graduating from the Huntsman Program last May. When not battling her latest round of intestinal upset or running from cows that chase her when she takes out the garbage, Dalal will admit that she has settled down rather nicely into life as a columnist for The Hindustan Times in New Delhi, India.