New Orleans after the storm.

By Nick Spitzer

The quiet of New Orleans is deathly. In a town once filled with noisemakers, revelers, Carnival celebrants, songsters, drinkers, raconteurs, and what the late banjo man Danny Barker called “night people”—a town where neon normally flashes, jazz and soul clubs beckon, restaurants and bistros teem with chattering natives and tourists alike in love with their chicken and andouille gumbo, dressed shrimp poboys, red beans and rice, oysters sardou (I could go on a long time with this list)—it’s that silent dark night over most of the city that still unnerves me.

My first encounter with the terrible silence, combined with the putrid smell of death and burned buildings, was on the inky fogged night of September 6, when ABC News got me back into the heavily guarded and vacated city to comment on the situation as a cultural catastrophe. A few nights before I found myself becoming, against all instinct, a disaster celebrity on Nightline—being questioned along with broadcast journalist Cokie Roberts, jazz musician Wynton Marsalis, and writer Michael Lewis. I mused off-air with Ted Koppel over the irony that they, all natives, had not lived in New Orleans for years and did not face or “taste the wave” as a local had begun to refer to the hurricane-into-flood experience. I, on the other hand, was a convert to the culture of America’s great Mediterranean-African-Caribbean—south of the South—home to jazz architects Jelly Roll Morton, Louis Armstrong, and Sidney Bechet; perch for writers Lafcadio Hearn, Faulkner, Tennessee Williams, and Walker Percy. I’d first landed in New Orleans just after college, at the end of a Kerouac-style road trip.

My emotions ran higher yet as I came back to my home city past the many levels of security—national guard, Louisiana state troopers, New Orleans police, private guards in black, all wielding machine guns—on a media pass. What struck me most was the absolute darkness and absence of people—except for clusters of soldiers—in a city famous for music, bon vivants, and nightlife. I camped out in a ramshackle media village of RVs and tents on Canal Street, the dividing line—or “neutral ground,” as it’s called—between the downriver French Quarter and upriver American Sector, now known as the Central Business District. Reporters fresh from the Iraq war were already cavalierly calling New Orleans the “wet Baghdad.” I resented that characterization and instead lulled myself to sleep with the thought of favorite songs I’d just played on my first post-storm American Routes radio program: Fats Domino’s eternally sad and mysterious song of return, “Walkin’ to New Orleans”; the schmaltzy, but now tear-jerking “Do You Know What it Means to Miss New Orleans?” performed by Louis Armstrong; Randy Newman’s mordantly fatalistic anthem, “Louisiana 1927” (with its famous line “Louisiana … they’re tryin’ to wash us away”). Another would continue to resonate: “Basin Street Blues,” a late 1920s romance sung by everyone from Armstrong to Harry Connick Jr. that first painted the city of Creole musicians, fancy plasterers, noted writers, street tap dancers, Mardi Gras celebrants, and culinary wizards, as a “land of dreams”—a place where one could always return to renew the spirit by sensory means of all kinds … until now.

Sleeping fitfully in a car at the news compound, I was awakened early for an interpretive walk through the Quarter and to my American Routes radio headquarters for the benefit of the evening news. I was pleased to see that my second-story studio on Royal Street was high and dry. I was grimly happy that the wind had ripped off a massive wooden gate and blown it up against the door, discouraging would-be looters. The improvised coat-hanger wire seal I’d left on the unlockable door shutters was still wound tight.

The TV crew left to file for World News Tonight. I walked alone across the deserted French Quarter, still shocked by the stillness—even the birds had been blown away—of what would have been a bustling day of workers, tourists, quirky long-term dwellers, and artists any time before Sunday August 28.

On that day I had awakened in my home a few miles Uptown to the news that this would be a Category 5 storm and immediately abandoned my New England-bred, “keep a stiff upper lip and ride it out” plan to take the family, including two young children, to a high-rise hotel for a few nights of expected disruption.

It has now been some four months since New Orleans, the city that adopted me, would then drown on national television and self-destruct in a thousand more tragic, intimate ways we have yet to fully know. The details of the storm—the levee breaks, the chaos of looting and breakdown of governance at federal, state, and local levels—are well known by now, even if one disputes the degrees, causes, and effects of the problems. Most of the city’s residents—at least those who are back or plan to go—have moved from mourning the loss of life and the displaced or destroyed culture of the cityscape as we knew it to a mix of hope, apprehension, and frustration about the future.

As a non-native, but one whose commitment to the local cultures of New Orleans and the French Louisiana countryside goes back 30 years, I find myself presiding over an internal debate most days. Should my family return to the Crescent City from our pleasant exile in Cajun and Creole French Lafayette, a three-hour drive west across the Atchafalaya Basin? We’ve set up modest housekeeping here, and with a reduced staff for American Routes we have been creating a thematic music-and-interview series called “After the Storm.”

That sense of not having a direction home—or, for many people, a house or neighborhood left to call home—remains the hardest thing to grasp in the aftermath of the multiple disasters of hurricane, flood, mayhem, and bureaucratic failure. That is one reason I have pressed to consider the cultural implications of the disaster. Native New Orleanians have historically stayed put far more than home folks in most cities. Outsiders who move there become converts, attracted by the melding of cultures at the neighborhood level: the music and second-line parades, Carnival and Creole cooking, fanciful vernacular architecture and street life of “The Big Easy.” Now with three-quarters of the population—mostly black and Afro-Creole—gone, is it New Orleans? Even if the city largely looks the part in the natural higher-ground areas (French Quarter, Central Business District, Garden Distict, and Uptown) along the river?

Although the French Quarter has come back to half-life, many of the offbeat places and people aren’t in the increasingly touristed old-city quadrant even in the best of times. Many of these New Orleanians—the soul of the city—are tucked away downriver in the mostly black 9th Ward, or in the Creole areas of the 7th Ward, including the Tremé neighborhood. This district is just north of the Quarter, home to many musicians and the famous second-line parades for social-aid and pleasure clubs that date back to the late 19th-century beginnings of jazz. In colonial times it was at the site of Congo Square, where slaves gathered on market days and Sundays to dance, drum, and trade with Indians and others. It’s these and other “back-a-town” spots—so named because they were beyond the original city, now the French Quarter, that fronts the Mississippi—that saw sickly dark water rising as high as 12 feet. This is the low ground that was sparsely settled and flooded before the levees began to be constructed in a big way in the 20th century, especially after the famous 1927 flood and the many inundations thereafter.

In recent visits to New Orleans the creative tensions among cultures and classes—so instrumental in the cultural landscape of jazz, the famed architecture and foodways—have shifted. It’s now a small, mostly white place of better-heeled Uptowners, the old Bohemians and hippies in the French Quarter and nearby Faubourg Marigny. New Orleans had its problems before the storm: poor public education, weak governance, limited economic infrastructure, a large underclass with many discontents, and an insular elite that has been unable or unwilling to lead economic expansion and inclusiveness. Now the problems are laid bare without the usual joys of community culture to offer balm or transcendence: in a musical moment, a passing parade, a corner restaurant, vast spirited neighborhoods built in wood or stucco of shotgun houses and Creole cottages in many variations and hues.

On August 28th, Royal Street—usually quiet and calm on a Sunday morning—was filled with a parade of New Orleanians coming from downriver neighborhoods. Black and white, old and young were dragging laundry carts and suitcases and heading somewhat feverishly to a variety of destinations: a car, a bus stop, the Superdome—now billed as a “last resort” for the infirm and those who couldn’t leave. It seemed a slow-motion Pompeii, with citizens facing not fire but water.

Returning home by car to gather the family and tape windows quickly—no time for plywood—we headed out for what we, like most, thought would be two to three days away—taking just enough to stay with friends in the Cajun Louisiana crossroads city of Lafayette, 140 miles west.

Leaving town on the old Airline Highway to avoid traffic on Interstate 10, we had a brief encounter that still haunts me. At a closed gas station where only credit cards could be used, I was approached by two young Afro-Creole women wearing large gold earrings and traditional colorful head scarves called tignons. In their beat up 1983 car sat five children, ages two to eight, all dressed for an outing. The ladies asked to use my credit card, insisted on paying for the tank of gas, and thanked me profusely, backed by a chorus of kids. When I asked in local lingo, “Where ya goin’, dahlins?” They answered excitedly, “The Super Dome!” I have wondered ever since what became of them. How I wish I’d told them to follow me west.

Now, with no natives or locals around the usually busiest parts of New Orleans, the idea that I was an exile in my own city began to weigh heavily. The horrific smells of death, the edgy occupiers, and now the sight of bodies, probably from the Lakeview neighborhood, that had floated down Canal Street toward our encampment made September 7, 2005, among my life’s worst days. A friend from ABC News suggested: “Nick you need to document your feelings about all this … just tape yourself.”

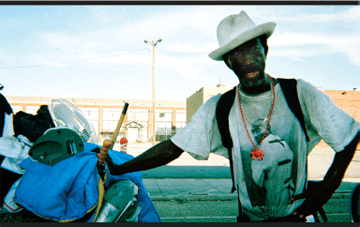

It hadn’t occurred to me to become the subject. I am used to listening to and recording others’ stories, putting them in archives and on the radio. Still, telling my own tale to myself—as a matter of record and relief—got me on the road Uptown to see the condition of my house. Along the way, more bodies, collapsed warehouse walls, the gift shop of the D-Day Museum looted, trash and dead animals, as well as an incoherent older man pushing a shopping cart of his life’s possessions (I gave him water as we attempted to converse). Another man hiding off Tchoupitoulas Street, near the levee Uptown, was guarding his family’s ramshackle apartment, walking their tiny prized dog, and carrying washing and drinking water from a swimming pool at a nearby mansion. I just narrated as I went—looking over my shoulder.

This perhaps foolish quest homeward grew frightening with nearby gunfire and passing armored-carloads of soldiers. I thought I might be shot as a looter by troops or attacked by looters who wanted my car, water, and food. This was the harrowing trip that made it onto the radio program This American Life—Ira Glass, the producer, convinced me to allow it on air. Documenting myself, I didn’t know my mind or emotions through much of it, but I felt that my angst and the audio was one way to help people across the country gain understanding through one small story—a tiny part of arguably the largest natural and cultural disaster in American history.

Near my house it was again terrifyingly quiet. Every gate creak and step on shattered glass of the rubble-filled streets seemed magnified. The neighborhood was a silent rotting salad of downed trees and plants, a tangle of power lines and jumble of trash, flies, and mosquitoes. The house itself—one we’d moved into just two months before—had only one window broken by hurricane gales. The hatch on the roof had blown open and there was water in the attic. The refrigerator was already molding, filling the familiar space with nauseating smell. I realized that while things were materially intact at the house, the social order of family and neighborhood around it had profoundly disappeared.

After a few hours hastily packing valuables and necessities—the baby stroller, clothes, family pictures, my three-year-old’s favorite Cat in the Hat video—I was tired and hot, since the power was off and there was no air conditioning or running water. I’d left the bathtubs full, thinking we’d return and need water to drink, wash, and flush with. Exhausted and dirty after two days in the city, I took a pleasantly cool bath, found clean clothes, and closed up the place.

Driving by night back to my new home in the media encampment, I ran into clusters of troops manning impromptu roadblocks in the darkness. The late-arriving National Guard now outnumbered the remaining 10,000 citizens about five to one; they knew neither the city nor the mission, and were clearly nervous. We were hardly all criminals—much of the less-obvious looting was for food and water—and we now know that many of the problems that were initially reported were, in fact, urban myths. I was stopped several times by young men about the age of my students—one with a flashlight, the other with a machine gun in my face. After the initial interrogation, when they realized I was harmless, they would invariably ask me directions for their patrol. If I was an exile in my home city, they were lost occupiers.

I am writing this just after All Saints Day—an important ritual occasion in dominantly Catholic south Louisiana. It’s part of the inheritance of colonizers and settlers from France and Spain in the 18th century, later joined by Irish and Italian immigrants, among others, in the 19th and 20th. New Orleans is home to the highest per-capita population in America of black Catholics, descended from the antebellum gens de couleur livre (free people of color) as well as French- or Creole-speaking enslaved people.

This time of year has long been my favorite—cool and sunny, not too many tourists, the cemeteries full of life as saints, souls, and family ancestors are recalled by re-painting the vaulted tombs, cleaning the graves, leaving immortelle wreaths (artificial flowers of wax and crepe paper), and attending candlelit services that bless the departed. But this year the cemeteries, usually bustling with the living, are empty.

As we now contemplate our return to live and work in New Orleans in the new year, the word-of-mouth and more official news is mixed. Some is uplifting: brass bands are out marching, followed by small crowds of second-liners; universities are re-opening, retaining more of their students than expected; the water is drinkable. Then the bad: houses may be torn down by the thousands; Memorial Hospital (where my kids were born) may not reopen; endless squabbles over power and priorities; the city has no tax base and is laying off 3,000 of the very workers who could help fix the place.

The New Orleans I knew lives in memory. That may be oddly appropriate for a city that has, for better or worse, long preserved and even obsessed on the past in its architecture, post-colonial lifestyles, and social relations. The New Orleans I hope for is in the imagination of all those willing to return to rebuild the intangible cultural community as much as the damaged cityscape, to demand coastal restoration and Cat 5 levees, neighborhoods restored by the many skilled artisans in the city, a WPA-scale approach to quality reconstruction. As for the New Orleans of today … we are all still exiles from the Land of Dreams.

Nick Spitzer C’72 is creator of Public Radio International’s American Routes, a weekly music and culture program produced in the French Quarter until August 28, 2005. Recently the Mellon Professor in the Humanities at Tulane, Spitzer teaches folklore and cultural conservation at the University of New Orleans.