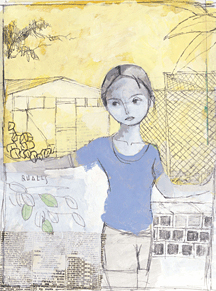

Spring break in the Dominican Republic.

By Sarah Blackman

At 6.30 on Monday morning I claw my way out from under my mosquito net and step with bare feet on the red ants swarming around my soap dish on the concrete floor of the ramada, which is not a hotel chain but a wooden pavilion with a sheet-metal roof. Orphanage Outreach staff have not yet rung the wake-up bell, but a donkey is braying loudly on the other side of the tarp wall, encouraging one of the roosters, bred next door as cock fighters, to cry, setting off a noisy chain reaction around the neighborhood. The dust in the warm air clings like a second skin as I dip my toothbrush in a glass of bottled water. A woman from Swarthmore sleeping just above me coughs herself awake as the residue of children’s hands takes root in her body.

Monday is my first day teaching English on a spring-break volunteer trip to the Dominican Republic. My teammate, Amanda, and I stayed up late pasting and coloring English words into a lesson, and at 7.30 a.m. we head to the front of the orphanage where all the neighborhood children gather to sing their national anthem and salute the Dominican flag, forming straight lines that begin at the flagpole and spiral out in an asterisk toward the street.

Trailing away to their classrooms, the children jump ditches full of broken cinder blocks and run around mounds of dirt that hide shards of aluminum and pieces of tires. Garbage bins don’t exist in Esperanza—part of Dominican culture is throwing plastic cups and empty milk boxes on the ground and sweeping everything up later—though the program director is starting a garbage bin fad at the orphanage.

Amanda and I work with a teacher called Rosa, who wears a dark-green pants suit that contrasts with a lime-green piece of elastic in her dyed auburn hair. The poorly mended seam in the seat of her trousers threatens to split when she leans over students’ desks. Rosa and the other teachers working near the Good Samaritan Orphanage are striking for higher wages. They teach half of the four hours assigned to them, or half an hour, or not at all. Forty-five minutes in, Rosa hands us her only piece of chalk.

The classroom is a converted chicken coop at the orphanage, crammed with resident boys plus 100 of the town’s children each morning. Desks totter—one leg on deteriorating cement and the other in a dirt hole; children without desks sit on the ground. There are no books and no maps for the classes; they are too easy to steal. Boys and girls in blue uniforms run in and out as they please and the coop is alive with voices like a playground. Some children finish copying Rosa’s notes from the small rolling chalkboard while others fight. And I can see André—an orphanage boy who curls silently in my lap at night and keeps an angry distance from the others—sitting in the back, no uniform, looking at the floor.

“Mi llama Sarah,” I yell into the chaos, using one of the few Spanish phrases I know. Girls are throwing rocks at each other when Amanda asks them what English words they remember from last week’s volunteers. We put up our poster of a man with his facial features labeled in Spanish and English, but only Rosa and a few eager children listen to the lesson. Going outside for Simon Says, most of the students run off to play games of their own. Across the street, though, there is noise from the construction of a brand new school.

Six years ago, before the Orphanage Outreach program had taken root in the Dominican Republic, the only person looking after the 30 boys who lived there, on the wasted property near the school, was “Papa Négro,” a kind, white-haired man with no resources of his own. The boys lived outside and showered in the rain; they had no access to medical care when they were sick or hurt.

Today, the grass is tamed with gravel, and ramadas—with their chain-link fences for walls and grooved sheet metal for roofs—house the boys. There are a hundred bunk beds for volunteers, all draped with mosquito nets and no more than two feet apart inside their own ramadas. The boys have sleeping and dining quarters, though they steal and sell their bed sheets, which are anyhow seldom missed in the balmy tropical nights.

Many of the boys still have health problems, including worms or parasites. Or HIV. Some who are brought here are really orphans; others have been abandoned; and a few—though circumstances have to be extreme to warrant police intervention in this developing country—have been rescued from abusive homes. Freddie, a 20-year-old Dominican with biceps and triceps that build permanent classrooms out of cinder blocks and dig irrigation systems underground, tells me over dinner that when the children ask about their parents, they are told a lie, “but no bad lie. Only that their mother and father are coming for them some day.”

The morning classes come in for a crash-landing around 11 a.m.; a moment of weakness gets me into the habit of walking Karen home. She is a fifth-grader in André’s class who carries a bright pink backpack that she shares with her younger sister. Shoulder height on me, she attacks with desperate pleas: Mi casa, mi casa! Come to my house! And though I am dying for a cold shower in the brominated water, I put on my straw hat and take her hand.

Karen lives in a neighborhood in Esperanza on the opposite side of a hill from the Good Samaritan Orphanage for boys. Small white chickens wander everywhere along the way, pecking at garbage. We pass a sky-blue house with wooden panels that don’t fit together, and I take a photograph of a monster pig tied to a tree in the yard. A family of four buzzes by on a moped, the father with a baby between his knees and another child balanced between father and mother.

The path we take runs through property separated from the dirt roads by two parallel lines of rusting barbed wire; Karen’s sister, smiling grandly as she catches hold of the top line between its sharps, stands on her tiptoes to hold the upper wire as high above the lower as she possibly can. I waddle through: right leg, dip the torso under, then left leg. “Gracias, mi amiga.”

As we descend through uncut grass and a second set of barbed-wire fencing, dirt roads appear ahead and the first houses have porches from which men make cat calls in their limited English: “Americana! I love you!” Small boys run to the edge of their yards to wave to the Americanas, stopping so close to the barbed wire that their naked bodies almost touch the metal.

Karen’s house is on the left. It, too, is bright mint green with a worn straw roof and no front door; her family has a small American car in the driveway. Inside, a partition divides a sitting room crammed with plastic furniture from the family’s bedroom. In the back yard, the family can duck behind a rusty piece of grooved sheet metal standing vertically, bent into a three-sided closet. We play tag and duck-duck-goose and I frustrate neighbors with my defective Spanish. One house, even smaller than Karen’s, has a living-room wall devoted to a poster of Claudia Schiffer.

Thursday is movie night, my last night with the orphans. Amanda and I correct the notebooks of the few day students that complete their assignments, filling in blank tables of expressions ourselves for the children who don’t. As the week progressed I found that some children didn’t work because they had no pencils to write with and that others, perhaps rightly enough, didn’t care to learn English. I continue flipping pages, remembering our second day of teaching and how the colorful, cut-out Bingo chips we made blew off the children’s boards with the faintest breeze. But when the kids solved the problem, covering our pictures of lashy eyes and brown ears with rocks from the classroom floor, “Beengo” became a popular hit, almost Monday’s redemption. A blank book turns up in the stack with only the name André written in the front cover.

I carry one chair for André and me, once the notebooks are tucked away, out behind the orphanage. Eager to watch The Jungle Book dubbed in Spanish together, we hug to say Hola and move closer to the TV screen, set up on the gravel in the humid night, before too many heads block his view. An hour into the film, a little white boy is living in the thick of an Indian jungle and I am smashing mosquitoes on my legs. André fiddles with his pocket and produces an American-made lollypop with bubble gum in the middle, but instead of chomping thoughtlessly into it, he waves it behind at me, shrieking a complaint when I try to give it back.

When the movie winds down, volunteers walk children to bed. André sleeps on a mattress without sheets or pajamas, without washing up, without brushing his teeth. He removes his shoes and, owning nothing else, stores them alone under his bed. All of the boys request hugs good-night from Americanas, and after I give one to André, I pull the lollypop wrapper out of my own pocket. “Gracias, André.”

We volunteers file out, watching the ground with plastic flashlights.

Sarah Blackman is a senior English major from Williamsport, Pennsylvania and a work-study student at the Gazette.