A hockey Hall of Famer reflects on his time starting fights as a player and breaking them up as a ref.

One day during his senior year at Penn, while driving the Zamboni and sharpening skates at the Class of 1923 Ice Rink, Paul Stewart C’76 struck up a conversation with some players on the Philadelphia Flyers, the two-time defending Stanley Cup champions who practiced at the arena.

Stewart was struggling to get on the ice as a senior, playing just three games and feeling like an afterthought in the coaching staff’s plans. When he shared his plight with Bob Kelly, the notorious member of the “Broad Street Bullies” advised Stewart that what mattered most for his future wasn’t his coach’s opinion, but Stewart’s belief in himself.

“I took his advice,” Stewart says. “I picked the worst team in the worst league. … They needed bodies—and they needed muscle.”

Stewart’s professional hockey journey started shortly after that conversation with a $14 bus ticket to Binghamton, New York, in December 1975, to play for an obscure minor league outfit—setting him on a path to become the only Penn alum to play in the National Hockey League. But that was not the end. He went on to become the first American to referee more than 1,000 NHL regular-season games, was inducted into the US Hockey Hall of Fame in 2018, and is now spinning his hockey career into a business that has taken him around the world.

A born raconteur, Stewart pivoted from hockey to storytelling with a weekly blog, a 2018 memoir titled Ya Wanna Go?, and a children’s book, A Magical Christmas for Paul Stewart (the proceeds of which go to the Ed Snider Youth Hockey Foundation and Ice Hockey in Harlem).

Despite his shifts drying up as an upperclassman on the Quakers’ varsity hockey team (which was dropped in 1978, shortly after his graduation), his memories of Penn don’t focus on what he missed. Instead, he fondly recalls a Russian history class with Alexander Riasanovsky—upon which he’d later draw as the director of officiating in Russia’s Kontinental Hockey League—as well as his time working the door at Smokey Joe’s (where his picture still hangs on the wall).

“I was grateful that [Penn] took me in and they gave me something I wanted,” says Stewart, who turned down interest from Boston College (for hockey) and Lafayette (for football). “I wanted an Ivy League education, because I grew up in Boston and I had to listen to all the crap they hoisted on me from all those Harvard guys.”

Desperate to play hockey somewhere during his senior year, Stewart trucked it up to Binghamton the day of his last fall-semester exam in 1975. (He finished his graduation requirements the following summer.) The Broome County Dusters of the North American Hockey League needed muscle, and Stewart was willing to oblige. In 46 games in 1975–76, he accounted for three goals, four assists … and a record 273 penalty minutes. That’s an average of one major fighting penalty per game. On his first shift, he got a souvenir of 23 stitches. Sewn up, Stewart finished the game.

“It was the movie Slap Shot every day,” Stewart says, referencing the 1977 cult classic about minor league hockey hijinks. Stewart—who was actually an extra in the movie, earning $500 and a script signed by star Paul Newman—carved out a niche as an enforcer that would make any Slap Shot character proud. It got him to training camp with the New York Rangers in 1976 before he returned to Binghamton, where he racked up 540 penalty minutes in 116 games over two seasons. The following year, he rose to the World Hockey Association, first with the Edmonton Oilers, then two seasons with the Cincinnati Stingers. He often returned to Philadelphia in the summers to train, learning aikido and boxing with Joe Frazier and Marvin Hagler.

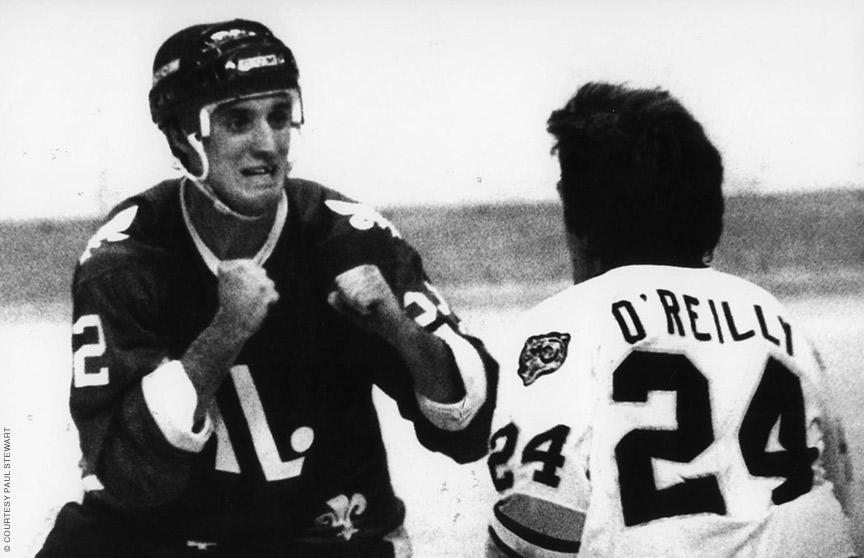

Stewart got the call to the NHL in 1979, debuting at the Boston Garden with the old Quebec Nordiques against the Boston Bruins, racking up 27 penalty minutes and getting into three fights in his hometown. He lasted 21 games in the NHL, scoring two goals during that 1979–80 season. Though his playing career continued through 1983, he never got back to the big league.

“I used my ability to fight just like a plumber uses a wrench,” he says. “It was a tool. It bought me the ice time I needed.”

Retirement posed a challenge. As punishing as life in the minors could be, it provided structure. While Stewart disavowed the “goon” label, he understood his role within the on-ice code: if you messed with one of Stewart’s teammates, you’d have to deal with him.

But with his hockey career over, his marriage in trouble, and a steady paycheck gone, Stewart was at another crossroads. “I went through a slump after playing,” he says. “I could’ve gone to drugs and drinking and gone stupid. Instead, I started coaching high school hockey and became a police officer. I was trying to find a niche.”

While searching, he dipped into his family’s past. His grandfather, Bill Stewart, had been a Major League Baseball umpire for 21 years, calling four World Series. (A fellow US Hockey Hall of Famer, he was the first American-born coach to win the Stanley Cup, with Chicago, in 1938.) His father, Bill Jr., refereed college football, baseball, and hockey, working games at Franklin Field and at 19 editions of the Beanpot college hockey tournament in Boston.

When Paul sought a life preserver, he reached for a whistle. “Sports wasn’t just an afterschool event for the Stewarts,” he says. “It was the way we made our living.”

Stewart started out reffing eight-year-olds for five dollars a game. He attended the NHL’s refereeing school, rocketing up the ranks on the strength of his skating ability and hockey mentality. He made his NHL debut in 1986 (again in Boston, where he was pressed into service when another ref got injured) and ended up logging more than 1,000 games before retiring in 2003, helming two Canada Cup finals, 49 Stanley Cup playoff games, and two All-Star Games.

It might seem incongruous that someone who made a career flouting the rules would then administer them. But the tasks are similar. As an enforcer, Stewart sought to keep opponents from going after his teammates. Officiating, while more dispassionate, still held the goal of safety and letting the game shine.

All told, Stewart lasted 28 years on the ice as a player and a ref—through a 1998 bout with colon and liver cancer (he later survived a brain tumor and melanoma) and a constant battering of his body. He now stands (with an artificial hip) as the only American that both played and refereed in the NHL.

“I loved being on the ice,” he says. “When I first put on that pair of skates and I went around the rink, falling down and getting up, falling down and getting up, I knew that was what I wanted to do.”

—Matthew De George

Great article

Stewy was a real character lol

Before I went to the NY Rangers rookie camp in 1977 @ Pointe Claire, Quebec Nicky ( Nick Fotiu) told me to watch out for him lol

They both roomed the yr before in training camp

Actually had a minor altercation with him during a harmless drill

I too played in the IHL for 2 seasons back in the late seventies When I stopped playing I also got into refereeing Well at age 68 I still referee and still enjoy it I guess this is my calling in life

Stewy stay well and be safe

Oh by the way My nickname you gave me was Flatbush at the NYR rookie camp

Thank you Alec. You mention fear but it is something that we all had to deal with every night we laced them up.

Going into WHA Birmingham, Edmonton or Quebec posed challenges that goal scorers didn’t have to face.

In the NHL, it was Boston, Philly or NYI that had both talent and lots of muscle.

My dance card was never empty.

I trust you are well and safe in these crazy times.

Yours, on and off the ice,

Stewy

Stewie

Remember who stitched you up

:-)

Doc

Smoothest scars I have. Thanks, Stewy

I played against Paul in the WHA and feared him every time I was on the ice against him. Then seeing him take up refereeing in the NHL I had the most respect for him and love to watch him on Hockey Night in Canada referring. He had a different respect than the other referees and I know why. Paul had played in the trenches, where others referees hadn’t. Professional hockey is a barbaric, fear challenge and respectful game and if you have experienced all of those you get respect, even as a referee… congratulations Paul and hope you are well… a long time admirer… Alec