One finds Alan Wright C’75 in a Shakespeare garden, up to his work boots in sage and thyme. Along with 16 happily muddy eighth graders at Westtown School in Pennsylvania, he is, he says, waking the garden to spring—raking away old leaves, pruning back dried stalks, laying in steaming piles of mulch. Look, he encourages his students. Smell. Think. Imagine. And here is lavender, and here, the seedpods of last year’s marigolds.

Later on this end-of-winter day, Wright will check in with his other teaching gardens—the potato garden that just yielded some 4,000 pounds of spuds, the garden of garlic and herbs, the perennials. He’ll drive his beloved maintenance vehicle to the place he calls the Mini Farm and walk between nascent raspberry bushes and the beds of early spinach. He’ll flip a plastic milk crate and consider it a throne and sit among the things that are almost green and surely growing.

Diminutive and charming, a hat smashed down on his head, Alan Wright has his heart in two places—here, at this progressive Quaker school, where he teaches earth literacy with his wife, Paula Kline, and in a town called León, Nicaragua, where he has been spearheading an extraordinary program of environmentally sound and economically sustainable change for years.

Wright’s passion for Nicaragua was stirred in 1984, when he and Paula, then finishing their doctoral programs (Wright at Yale, Kline at Harvard) grew concerned about U.S. policy in precarious Central America and joined a Witness for Peace delegation on the border of Nicaragua and Honduras. “We prayed and sang songs,” he remembers now. “We stood in solidarity. We let it be known that the city council of New Haven had adopted León as a sister city.”

The trip, Wright says, was utterly transforming—the beauty of the country, the culture, the people; the startling realization that half the population was under 15 and yet committed to social justice, literacy, and education. “They were tiny people,” Wright says, “and they were heroes.”

Back in New Haven, the Wrights and their cohorts began to turn the sister-city project into a national sister-city movement. By 1989, 100 U.S. cities had adopted towns throughout Nicaragua and had begun, through that means, to link together health-care providers, artists, teachers, trade unionists, educators, and the like. Knowledge, hope, optimism journeyed back and forth, across the border.

But by 1989, the Nicaraguan economy had begun to implode, and all the good work that was being conducted under the auspices of the sister cities was imperiled. “It became painfully clear that preschools, women’s centers, trade unions, art are all predicated on a viable economy,” says Wright. And when the economy collapses, he adds, so does that fragile infrastructure.

No longer able to effect change from afar, Alan and Paula moved their family, which now included a one-year-old daughter and a four-year-old son, to León in July of 1990. In a dilapidated, leaking, adobe house, they set up shop on a sister-city stipend. Their daughter danced naked in the street. Their son quickly became bilingual. Paula began training community preschool teachers, while Alan consulted to a women’s weaving cooperative.

Soon he understood that a new step had to be taken—that credit had to be extended to local entrepreneurs if the community was to have a chance at survival. Back to the States the family went to raise $75,000 of seed-loan money from family and friends. When they had what they had come for, they packed up their things again and returned to their adopted city.

Just how $75,000 became the lifeblood of an entire León neighborhood is a story Wright tells with a twinkle in his eye, a bit of mischief. No, he’ll admit, he wasn’t absolutely certain that he could make his dream come true. No, he didn’t really know for sure how the puzzle pieces would fall together. But he had faith and he had passion, he had love for a people in his heart, and the only alternative was not to do anything at all, an option he would never entertain.

By the end of the process, even the Spanish government had contributed $20,000 to the fund and CEPRODEL, a Nicaraguan non-governmental organization, had signed on to administer the monies. “We made the decision to do all our work” in Río Chiquito, the poorest neighborhood in all León, Wright says. “CEPRODEL came right in and set up its shop and started going door to door, asking the families of Río Chiquito if they had a small business they would like to see grow, if we could be of technical or economic assistance.”

Tortilla makers, uniform makers, firework manufacturers, tanners, a man who repairs automobile engines, and hundreds more responded. With average loans of four months’ duration and $300 in value, the people of Río Chiquito got on their feet. Incredibly, 98 percent of those loans were paid back.

But if Wright was tempted to believe that he had realized his dream, the bare facts of Nicaragua were not about to let him rest. By 1994, the rural economy of León, utterly dependent on cotton, had completely bottomed out. “As we are about to leave León, the cost of producing cotton began to be higher than the international commodity price,” says Wright. “And all of a sudden the farmers stopped growing cotton, the land went idle, the whole rural economy died, and the campesinos began crowding the city, where there was simply not enough housing or food or education to support them. Here was Nicaragua, with the best land distribution in all Latin America, and no one was growing anything. It was a crisis.”

Hoping to apply the urban lending model to fallow cotton country, Wright and his colleagues bought a piece of land and, with the help of grants, engineers, University professors, and campesinos, began to convert it into a model farm. They modeled drip irrigation and fertilizing with compost, demonstrated the value of micronutrients and integrated pest management. They dug in and then they prayed, but the first year a drought destroyed all of their crops and the second year the model farm was devastated by Hurricane Mitch. It became painfully clear, says Wright, why the campesinos had long before given up trying to grow in that part of the world, where a drought and rainy-season cycle makes year-round farming such a vulnerable proposition.

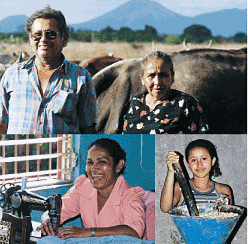

But Wright, the dreamer who finds sage and thyme at the end of winter in a garden named for Shakespeare, refused to give up, to see the program die. Instead, founding an organization called SosteNica, he raised $250,000 to model, herald, and implement, among other things, an agro-ecological approach to farming in the devastated cotton region of León. He introduced the concept of small wells and irrigation, of using the 15 feet of water that runs just beneath the surface of that earth to nourish the land of the campesinos. In the SosteNica program, every qualified farmer is given a topographical map of his or her farm, a plan for ditch irrigation, training in the growing of non-conventional crops, a pump, some irrigation tubing, and some $1,500 in loans so that they can grow year round. Seventy-five families are already participating. And the earth, Wright says, is responding.

Determined to now raise $3 million for the program, he is ecstatic about the changes he sees in León. “I just came back from visiting four of the families that SosteNica supports, and I tell you, it made me weep,” he says. “You drive through a desert landscape and up a little rutted path and there, all of a sudden, is an oasis in the desert. There’s passion fruit and mango and papaya and watermelon and squash and plantains, and the ground is moist and the air is cool and the people are really making it. They’re feeding their own families, they’re selling the excess to local markets or a Costa Rican supermarket chain. Eventually this kind of surplus will help to feed the rest of Central America.”

They’re paying back their loans, Wright says, and they’re standing tall, and, if he has anything to say about the future, this is just the beginning of a good green movement.

For more information, please contact SosteNica at (www.sostenica.org).

—Beth Kephart C’82