Sri Lanka bombards the senses.

By Harris Steinberg

When the call came in the late summer of 2005 about a possible Penn expedition to Sri Lanka, it might as well have been about a trip to the moon and back. I had learned about Ceylon in grade school, but somewhere along the line it had morphed into Sri Lanka, a remote island-nation somewhere in South Asia that was little noticed in America—until it was thrust into terrible prominence with the December 26, 2004, tsunami that killed over 35,000 people and left almost one million homeless along 600 miles of coastline.

The invitation to visit the country had come from the U.S. ambassador to Sri Lanka, Jeffrey Lunstead Gr’77, who was hoping to build civic capacity through higher education by establishing long-term links between the country and the University. Six of us from Penn, representing the School of Design, the Graduate School of Education, and the Solomon Asch Center for the Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict, traveled to Sri Lanka in February 2006. The Asch Center was already engaged in important work within the parts of the country contested by the rebel group known as the Tamil Tigers, but the rest of us were new to Sri Lanka.

We doggedly fanned out across the island, listening, observing, and making contacts with officials and many other people in the hopes that we could find the spark that would ignite a long-term relationship. I came prepared to investigate the current state of urban design and planning—and left intoxicated by the ancient rhythms, pungent aromas, and the layers of history that have fertilized the land.

An island about the size of West Virginia perched like a teardrop off the southeast coast of India, Sri Lanka is an ancient stop along the Indian Ocean trade route. The vast majority of its 20 million people are Buddhist, with Hindu Tamils and ethnic Muslims comprising small minority populations. The island was originally settled nearly 3,000 years ago by migrants from northern India who came across the Palk Strait.

Over the centuries, warring Sinhalese and Tamil kingdoms battled for control of the island, leaving archaeological sites rich with art and the evidence of advanced technologies and irrigation methods. In 1505, the Portuguese came in search of the lucrative spice trade, only to be cast out by the Dutch, who were overtaken in turn by the British, whose sway extended for over 150 years until independence was granted in 1948.

Sinbad the Sailor is said to have visited the lush tropical paradise, naming it Serendib, the origin of our word serendipity, or accidental good fortune. Today, Sri Lanka’s fortunes are anything but good. Wracked by 23 years of civil war between the Sinhalese-Buddhist majority and a fractionalized Tamil-Hindu minority battling for an independent state in the north, the country still reels from the aftermath of a bloody ultra-rightwing insurgency that terrorized the country in the late 1980s and early 1990s. As a result, Sri Lanka has experienced a fraction of the foreign investment and largely missed out on the economic growth that has benefited most of Asia and India in the past 20 years.

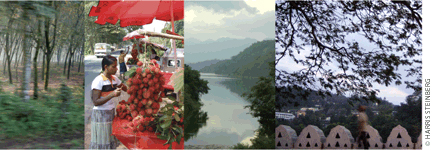

This is a land where sarong-clad men and women living beside rice paddies dip clay pitchers into streams within sight of a cell-phone tower. Where lithe, skilled garment workers (who literally make the shirts on our backs) stroll beneath sun umbrellas deep within the mountains of the Victoria Sanctuary, outside the ancient capital of Kandy. A land of indigo and ochre batiks set against the dazzling sun, and breathtaking beaches with million-dollar views that teem with fishermen who earn just dollars a day.

On the dusty, cluttered, dirty streets, vendors sell a rich variety of local fruits, nuts, and vegetables—rambutan, pineapple, jackfruit, mangoes, coconuts, cashews, and eggplants. Ancient subsistence collides with modernity. Orderly, polished temples are set beside ramshackle huts. The air is fragrant with curry, fish, and spice—and, in the capital of Colombo, thick with car exhaust and cigarettes. Along the roadside, Bo trees are encircled by shrines to the Buddha, the ground around them strewn with flower petals offered by the faithful. There is a constant military presence in the capital and in the contested areas, and a palpable feeling of precariousness, along with many reminders of the pervasive poverty that lies behind the bright smiles of the country’s inhabitants.

On this preliminary trip, we covered about two-thirds of the country, meeting with cabinet-level ministers; heads of universities, professional groups, and non-governmental organizations; leading urban designers, architects, and intellectuals; and businesspeople.

We dined with Senake Bandaranayake, the renowned Oxford-trained archaeologist who presided over the dig at Sigiriya, one of Asia’s most significant sites, in a fashionable restaurant called the Gallery Cafe. Tucked away from the urban disarray that consumes the city, the restaurant was in the former offices of Geoffrey Bawa, Sri Lanka’s leading London-trained architect, who fused a sensible modernity with a rich love of the vernacular to create an authentic Sri Lankan contemporary architectural expression.

We also met with the Sri Lankan minister of housing and construction, the Honorable (Mrs.) Ferial Ashraff. Draped in an elegant blue-silk sari and headdress, she graciously hosted us at her home behind the walls of a heavily guarded government compound. While a houseboy silently filled our china cups with sweet tea and milk, she spoke with obvious feeling to urge our support for expanding Southeastern University of Sri Lanka in the remote fishing village of Oluvil on the east coast. We later witnessed the devastating effects of war and neglect on Ampara, a town in Minister Ashraff’s home district. Located in a Muslim area within the Tamil-contested lands, the town is in desperate need of new homes, jobs, and investment.

We visited the shrine to Kataragama, a remote pilgrimage center important to Buddhists, Hindus, and Muslims, where we witnessed fruit offerings to the god and flaming coconuts hurled to the ground in a ritual to foretell the future. In the Batticaloa district on the tsunami-ravaged eastern coast, we saw scores (of the 60,000 country-wide) new houses being built beyond the barbed-wire checkpoints where government troops patrol by day and the Tamil Tigers rule by night.

Our purpose in making the trip was to build long-term associations around our respective disciplines, but we couldn’t help but filter our thinking through the devastation that had been wrought by the tsunami. Reminders of its impact were everywhere. Some people still inhabited half-standing ruins, with dark rooms set against the brilliant coral-strewn sea. Others lived in coconut-thatched temporary housing built by foreign NGOs. Still others were moving into government-mandated new housing.

And yet, despite the magnitude of the tragedy and the initial death toll, we were astonished to learn that not a single Sri Lankan had died from dysentery, disease, or lack of food after the deadly waters receded—this in a country with no highway system, where it can take five hours to drive 50 miles along the congested Galle Road south of the capital. The comparison to the U.S. response to Hurricane Katrina was unavoidable and haunting. How could a country with a fraction of our resources face up to a calamity of such magnitude so humanely, while in the wealthiest and most powerful nation citizens died in the chaos after a storm?

Our trip was productive, illuminating, and humbling. We made many contacts and established the basis for what could be a long-term engagement between Penn and Sri Lanka. We were welcomed with open arms, and in Penn Design we are working on setting up projects for our faculty and students that can keep the momentum going while we think about how to institutionalize a relationship around urban design and planning.

For an architect trained to read the built environment, Colombo is maddening. I was unable to make out any patterns within the Sri Lankan man-made landscape, which was without a single organizing spatial concept that would make sense to the Western eye. Construction elephants lumber down main streets in the capital. Animals graze languidly within the central urban park. Urbanism as we know it doesn’t exist.

But then, Sri Lanka is not the West, where we are concerned for outward appearances and carefully order our world. Sri Lanka swirls in a dizzying array of color, light, and heat. Richly spiced, it is a world alive to the senses and the soul.

Harris Steinberg C’78 GAr’82 is an adjunct assistant professor of architecture and executive director of Penn Praxis, the clinical consulting arm of the School of Design.